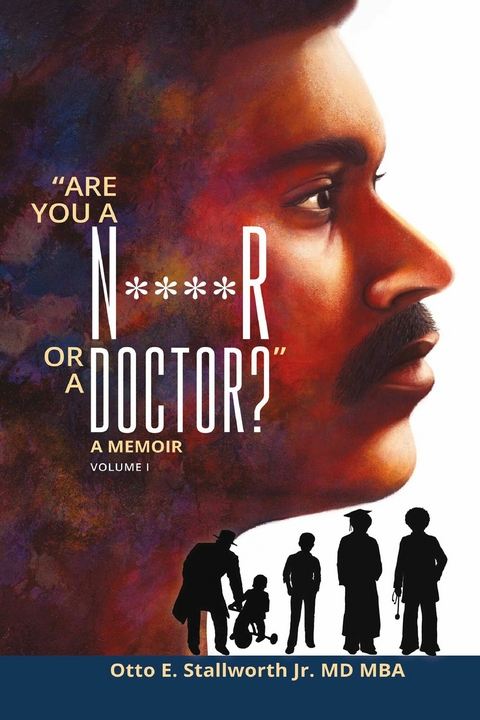

"e;Are You a N****r or a Doctor?"e; (eBook)

286 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-7112-7 (ISBN)

Dr. Stallworth, the author, was born and reared in Birmingham, Alabama, during the 1940s 50s, and early 60s, a city characterized during those years by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. as "e;the most segregated city in America."e;Crossed the Alabama state line for the first time at age 16 in 1962 to attend Howard University in Washington, D.C., and became the first college graduate in his family. The details of Dr. Stallworth's life are evocative of friendships, falling in love, and marriages; and a great variety of occupations ranging from discovering and managing a famous music group todriving a city bus on his first trip to Chicago, to becoming a doctor. His writing style itself is clear and effective, quirky and compelling, especially the description of friendships from early childhood on and falling in love, and the humorous stories. There are sad times described, and traumas and problems, but Dr, Stallworth gives these a full range of emotions and I think the reader really feels what he felt, or close to it. Probably more important, the reader can learn from it.

Chapter 1:

Lincoln Park, the White Soldiers, & the Thing

A White boy and girl walked at a carefree pace towards us as Colley, my neighborhood friend, and I played in the woods behind my house. Dressed in army gear, at first glance, they made us uncomfortable because we had never seen White kids, especially 10- or 11-year-olds, our age, not in our neighborhood, Lincoln Park, a Colored neighborhood, not even as passengers in a car. Not in 1956 Birmingham—which, according to Martin Luther King, Jr., was “the most segregated city in the United States.”

My parents, Addie B. and Otto, Sr., bought their house shortly after their marriage in 1941, on a half-mile street that dead-ended at a large, solid, opaque iron gate with large letters that read “Lincoln Park.” Named after the developer, not the president.

There was undeveloped land south and west of Lincoln Park. But there were plans in motion to develop the land in all directions. Behind my backyard, going west, was undeveloped woods, which my friends and I often explored.

As we came closer to the two White kids, we could see they wore the same army gear we wore, including the white ankle spats. The White boy spoke with a Southern drawl, as he said, “I see y’all found the army stuff,” as he glanced towards the stack of military supplies that Colley and I had rummaged through a week ago.

“Y’all live around here?” I had to ask.

“Right over yonder.” We could only see trees and bushes where he pointed, no house. “I’m Jack, and my sister’s Caroline.”

That they lived nearby was a shock, because I never knew White people lived so close to us. Jack’s hair was sandy brown and somewhat kinky, like my neighborhood friend Michael’s hair. Michael was Colored but light-skinned. And according to Michael, White people always asked him if he was Jewish.

“Are you Jewish?” I asked Jack.

Jack took a second to answer. “Yeah, but my dad won’t say that. He dropped berg from our last name before he moved here from New York.”

“Why?” Colley asked.

Caroline had straight, dark brown hair. Nothing Colored-looking about her, and one year younger than Jack but taller and spoke in a slow drawl. “Our dad said KKK stood for Koloreds, Katholics, and Kikes all with a K for KKK. The Ku Klux Klan hates all of them, including Kikes.”

“That’s weird. Why do they hate kites?” Colley asked.

Caroline belted out a laugh, then gave a mini-smile and said slowly, “Not K-I-T-E but K-I-K-E,” and said that for Jews, it’s like saying nigger. That word, stained by her Southern drawl, bordered on offensive, because we had never heard a White person other than White politicians on TV use that word, and she used it in such a matter-of-fact way, not in a demeaning way, and that was disarming. Colley eyeballed me but said nothing.

We followed them and saw their house, which was mini-colonial-style and camouflaged by overgrown ivy and green foliage. Their house was twice the size of my house and, from its appearance, twice as old. Never went inside or got too close or met their parents, and vice versa. By basic instinct, we never considered or discussed it.

After the first day of our chance encounter, Jack, Caroline, Colley, and I sequestered ourselves in the woods and played army every day. We explored the bugs, the green snakes, the tadpoles, and the crawfish; chased the rabbits; swam in the creek; and raided the huge pecan trees until after dark.

Our favorite time of day was dusk, especially after a rain shower. That’s when the grass and rain combined to release a sweet aroma reminiscent of watermelon. And lightning bugs performed unsynchronized flashing light shows with their neon-yellow bodies, which hovered helicopter-style, creating a dreamlike vision over the green grass and foliage. It was mid-air bug ballet.

Jack and I discovered two things we both loved: comic books and marbles. We both had enormous collections and traded both. My favorite comic books were his favorites—Superman, Batman, Plastic Man. And we had one other thing in common—we were both curious about what I called “the Thing” and what he called “the Tree.”

The Thing was a structure high on Red Mountain, which we could see from almost any location in Birmingham, but from our close-by neighborhood in Lincoln Park we had a perfect close-up, panoramic view. Red Mountain bordered Birmingham’s city limits on the south and was, appropriately, called “Red Mountain” because of its rust-stained rock and large seams of red iron ore that gave the mountain a dark red hue.

I called it the Thing because that’s the first word that came to my six-year-old mind when I first noticed it. “What’s that thing?” And the name stuck. Jack called it the Tree because he thought it was a tree. There were many opinions around the neighborhood regarding what it was.

One day, underneath one of ten humongous pecan trees on the side of the small creek, we tossed large sticks into the trees and scattered to avoid the pecans that fell like rocks from its branches. We sat in a circle, cracked the pecans with our teeth, and in between chomping on the pecans, we debated the Thing.

“Sunny, you think it’s metal or wood? I say it’s got to be a tree,” stated Jack.

“If that’s a tree, it would have leaves,” I said.

“Not in the winter,” Jack replied.

“It’s summer,” I reminded him.

Caroline added, flavored by her drawl and a mouth full of pecans, “I know, I know. It’s a totem pole.” Followed by a giggle.

Colley stated with authority, “A totem pole? There ain’t no Indians around here. It’s summer... No leaves... It’s an old telephone pole.” Colley pondered, stood, and said, “Why don’t we go see it for ourselves? It’s not that far. It’ll be fun.”

“Yeah, we can wear the army stuff. Pretend we are on a mission,” Jack replied.

We met early the next morning in the woods, next to the army supplies, and put on helmets and vests. None of us had been to the other side of that gate, and Colley, Jack, and I had just climbed halfway up when Caroline yelled. “Hey y’all, over here. Y’all don’t listen. I’m on the other side.”

“How did you get over there?” Jack asked.

“Tried to tell y’all. You just walk through them bushes down that way.” She pointed to our left.

We walked 25 feet to the left of the gate and found tall weeds and bushes, no gate, no fence. On the other side, to our surprise, the streets were black asphalt. There was one long street that continued as Center Place Southwest, and two paved streets that formed two separate circles, one small and one large, and a large sign that read “Honeysuckle Circle.” No sidewalks, no houses, no grass, and no signs of construction.

We continued walking south towards the Thing but stopped to look at a large, older house at the highest peak of Honeysuckle Circle. A brown wood house with large unobstructed, cream-colored framed windows surrounded by mature vegetation, which was a green oasis amongst the brown dirt and empty streets.

Jack looked and sounded jittery. “My dad told me the old lady that owned all this property lived in that house. She wouldn’t sell. She died, then there was some legal stuff going on and they got the land. But they say her ghost haunts the empty house.”

Colley was excited. “A Colored lady? Was she Colored?”

“White,” Jack answered.

Thin, white see-through curtains covered the windows. At that moment, a shadow moved across a window, which caught our attention. The curtains fluttered. We saw the shadow and the fluttering move to the next window, and to the next window and the next.

Colley shouted, “Ghost!” and he took off running. We ran behind Colley into the woods. After we felt safe, we flopped to the ground exhausted, and laid on our backs in a flat grassy area surrounded by tall pine trees that framed the blue sky we could see high above us. Caroline, in between breaths, said, “That’s y’all’s imagination. No such thing as ghosts.”

Colley responded, in between gasps, “What was that in those windows then? Nobody lives there.”

“The wind,” Caroline said.

“Got to get going,” I yelled. “Let’s cross the street up ahead. After that, according to this map I found at home, there’s just a railroad track between us and Red Mountain.”

At a lull in the traffic, we scrambled across the street, as our oversized army helmets rocked on our heads. Just as we reached the curb on the other side, a police car passed, slowed, flashed red lights, blasted the siren, made a U-turn, and parked on the side of the street where we were standing.

I knew Whites and Coloreds together could get us in trouble, and I had an idea. I turned to Jack. “Your name is George Peterson, and that’s your sister, Darnell.”

The two police officers stood by their car with red light flashing and exchanged words for a minute or two. We took seats on the ground. George Peterson, who I had known since kindergarten, looked as White as any White boy. He lived in the neighborhood, and almost everyone in the neighborhood knew of the lady with the White-looking son and her daughter, who had medium brown skin and curly hair like her mom.

The bigger, older cop walked towards us slower than molasses. He had beads of sweat on his forehead and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.12.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-7112-9 / 1667871129 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-7112-7 / 9781667871127 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,1 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich