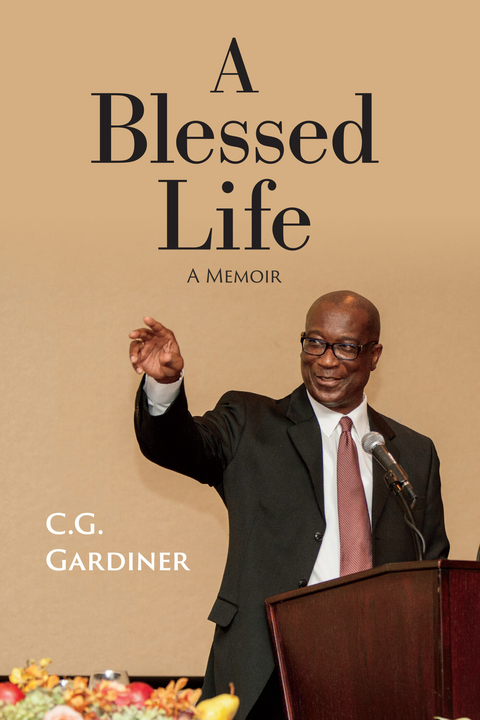

Blessed Life (eBook)

558 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-0093-6 (ISBN)

A BLACK MAN, BORN AND RAISED IN THE CULTURE OF THE CARIBBEAN, ACCUSTOMED TO POLITICAL DISCRIMINATION, BUT UNACCUSTOMED TO AMERICAN SYSTEMIC RACISM, CONFRONTS BOTH IN THIS ENGAGING AUTOBIOGRAPHT BY C. G. GARDINER. HIS IS A STORY OF DETERMINATION, PERSEVERENCE, AND GOOD FOURTUNE. IT IS A WELL WRITTEN AND "e;READER FRIENDLY."e;

CHAPTER 1

1947 - 1957

Touch and Go

I was born in Grand Turk, the capitol of the Turks and Caicos Islands (the TCI) in 1947. A few years before my mother died, she told me that I was a premature baby. I wasn’t expected to live. She was seventeen, and it was a difficult pregnancy. My survival was “touch and go” for two days following my birth. But I was the first grandchild of both of my parent’s families. Both families were determined that I should live. And they did whatever was necessary to ensure that I did.

The TCI is a collection of islands located northeast of Cuba, and slightly northwest of Hispaniola (the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Grand Turk is one of the smaller of the inhabited islands at approximately seven square miles.

The TCI were devoid of inhabitants for much of its early history. The Taino Indians inhabited the islands between 750 and 1300 AD. The Lucayan Indians followed them, beginning in 1300 AD. Columbus “discovered” the islands in 1492. He brought European diseases and cruelty with him. Because of this, the Lucayans had been brutally wiped out by 1520.

With the arrival of the Europeans, the need to preserve food - primarily fish and beef - became critical. Consequently, there was a great demand for salt, not only for food preservation during the long trans-Atlantic voyages, but also for sale to the American Colonies. Salt became so valuable that it was regarded as “white gold” by the Europeans. The TCI had natural costal flats that flooded at high tide. And salt ponds naturally appeared under the relentless pounding of the tropical sun. Because of its salt producing properties, the TCI became a coveted territory. They were claimed by several European countries - including France and Spain - at various times.

The TCI had come under the control of the British by the end of the sixteenth century. Britain considered the islands “uninhabited,” and declared them “common property,” available for exploitation by any of its Colonies. Both the Bahamas and Bermuda wanted to exploit the TCI for its salt. This caused years of legal wrangling between the two countries for control of the TCI.

Bermudian merchants established salt raking operations in the TCI in the sixteen-hundreds. They, along with their slaves, would occupy the islands for the six months of the salt raking season. They would return to Bermuda with their product at the end of the season. They cut down most of the trees in the salt producing islands where they operated. This was to discourage rainfall, which is detrimental to the production of salt.

By 1725, there were approximately a thousand men harvesting salt on Grand Turk during the salt “raking” season. Britain had solidified its control of the islands and had imposed regulations governing the salt raking activities. In 1783, following the end of the American War for Independence, many British Loyalist fled America and settled in the TCI. Most brought their slaves with them. The British Government granted the Loyalist plots of land for cotton farming, primarily on North Caicos, Parrot Cay, Middle Caicos, and Providenciales.

Grand Turk was designated a Customs port of entry for the TCI in 1792. Britain settled the dispute between the Bahamas and Bermuda over the TCI in 1799. They placed the TCI under the jurisdiction of the Bahamas, even though most of the inhabitants were Bermudians.

Most of the Loyalist had left the TCI by 1820, having failed at their attempt at cotton farming. They deserted their slaves, leaving them to fend for themselves. Haiti had decreed its independence from France in 1804, following their successful revolution (1791-1804). The revolution had caused a stirring for freedom in the slaves in the TCI. Hundreds of them fled to Haiti in 1821, following the departure of the Loyalist.

In 1834, Britain freed the slaves in all its Colonies, including the TCI. In 1848, Queen Victoria granted the TCI a Royal Charter. The TCI thus became an independent country. However, it was unable to support itself financially. Consequently, in 1874, Britain once again placed the TCI under the jurisdiction of Jamaica. The TCI chose to remain a British Colony when Jamaica gained its independence from Britain in 1962. It remains a “British Overseas Territory” today.

Economic Decline

The nineteen-forties and fifties were an economically challenging time for the TCI. The salt industry was in decline by the time of my birth. The Bahamas had developed its own salt industry in the nineteen-thirties, when the Ericksons - three American brothers - developed a mechanized operation on the island of Great Inagua in the Southern Bahamas. With the introduction of modern methods and machinery, the Bahamas had begun to displace the TCI as the preeminent salt producing country in the region. The displacement was assured when the Ericksons sold their operations to the Morton Salt Company in 1954.

As the need for manual labor in the salt industry declined, the TCI Government and the American military base on Grand Turk (established in 1950) became the country’s two largest employers. Those not employed in the declining salt industry - or by the Government or the Americans - made their living primarily as fishermen. In addition, many young men (including my father for a time) became merchant seamen for one of the Dutch shipping companies operating in the Caribbean.

The population of Grand Turk couldn’t have been more than a few hundred people in 1947. The vast majority were of African descent. I cannot recall ever seeing a White person during my early years there. No doubt they were there - considering the presence of the American military base; but I cannot recall ever seeing one. There were two people though, who looked White to me. One was my maternal great-grandmother, Grandma Lizzie, who was a mulatto, born in the Dominican Republic. The other was a “Mr. Spencer,” who I remember only because he asked to use our outhouse one day, in my presence.

Grand Turk was a tight knit community. Family relationships were extensive. There were few strangers. And economic suffering was a shared experience. Merchants allowed customers to purchase goods on “trust” (that is, on credit). My mother often sent me to “trust” goods from Mrs. Irene Godet who had a shop down the street from us. Our house was on a corner of Grand Turk’s front street, facing the ocean. A stonewall surrounded the property at the time. Facing the property, on the other side of the road, was a seawall. Diagonally across from the property was the “Cow House,” where animals - mostly cows - were slaughtered. It was a small, shed-like building. It sat on a concrete platform constructed directly on the beach.

To me and my friends, slaughter day was a festive occasion. People gathered at the Cow House, amid jokes and laughter. My friends and I would linger at the edge of the crowd, watching. As the cows were slaughtered, some of the men would catch the blood draining from their necks in tin cups. They would drink the blood. This fascinated me and turned my stomach at the same time. I didn’t like the sight or smell of blood; but I thought it must have a sweet taste - otherwise, why would the men drink it? Of course, I had no conception then of sexual prowess or physical strength. But no doubt the custom was fueled by the desire to increase both.

Mama, my paternal grandmother, was the owner of the property on which we lived. My grandfather, Christopher “Christie” Gardiner, had died, leaving her with three young children - my father, who was nine at the time; his older sister, Vivian (Aunt Vivie) eleven, and the youngest child, Aunt Uda, who was seven. Aunt Uda had married and moved to the Bahamas with her husband, Calvin Duncanson, by the time I was three or four. I would not meet her until I was ten years old - after we had moved to the Bahamas.

There were two houses, a water tank, and an outhouse on our property. Mama, Vivie and her daughter, Grace, lived in the bigger house. My parents, my brother Clayton - two years my junior - and me, lived in the smaller house. Both houses were plain, unpainted, wooden structures - as were many of the houses in Grand Turk at the time.

Grandma Julia, my maternal grandmother, like Mama, was a widow. Her husband, George “Georgie” Forbes, had been a merchant seaman. He died when his ship was torpedoed and sank during World War II when my mother was a teenager. His service was later recognized by the TCI Government. In addition to my mother - the second oldest – my grandparents had four other children: Robert, the oldest; then following my mother, Simeon (Sim), John, and Gracita (Cita). Grandma Julia’s mother, Grandma Lizzie, lived with her. I remember Grandma Lizzie as a boney old woman with sparse, stringy, white hair, and a pale, white complexion. She walked - bent at the waist - with the help of a long, wooden staff.

Grandma Julia

I spent a lot of time at Grandma Julia’s house. Two of my playmates were my cousin Jean (Uncle Robert’s daughter) and a girl nicknamed “God Bird.” Grandma Julia’s house was quite different from Mama’s house. It too was constructed of wood; but where the rooms of Mama’s house were unadorned, Grandma Julia had covered the walls of one room (at least) of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.11.2021 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-0093-0 / 1667800930 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-0093-6 / 9781667800936 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 11,4 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich