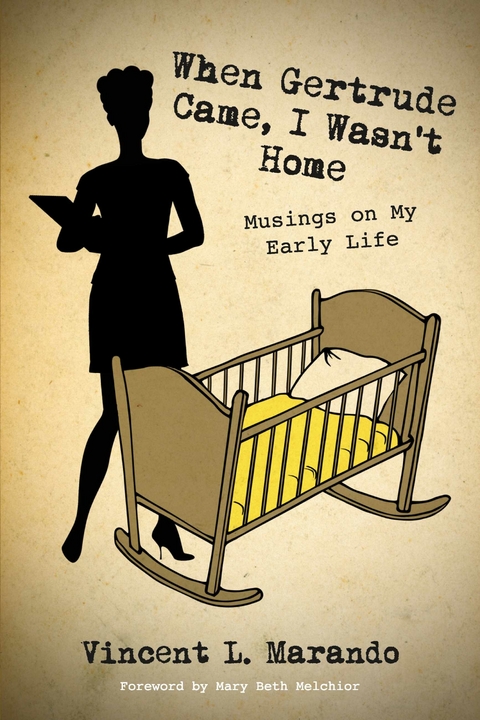

When Gertrude Came, I Wasn't Home (eBook)

192 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-0101-8 (ISBN)

"e;When Gertrude Came, I Wasn't Home"e; is the story of the child of immigrants living in Buffalo, NY. Sickened by a pandemic, he labored in the fields, picking berries and beans. Despite the adversity, he found his way to the American dream, eventually earning his Ph.D. and going on to become a full professor at one of the nation's top public universities. This is the story of Vincent L. Marando - the son of Sicilian immigrants, a polio victim, a competitive swimmer, and - eventually - a successful professor of political science. This is a story that takes place from 1938 to 1952. This is a story of the ways America has dramatically changed, and not changed at all. At its most basic level, this compelling story introduces us to Vince's colorful immediate and extended family and explores the events of his childhood that had a profound impact on his adult life. We meet toddler Vince (and his family) coping with polio and its after-effects. We meet a young child exploring his world with his friends - including going to a wake or two. And we meet the 'tween Vince, finding out that his work ethic could take him to new heights in athletics and in scholarship. But this story is about so much more than one man's coming-of-age: it is the story of how America has dealt with pandemics, immigration, the census, and the challenges of fulfilling "e;the American dream"e; as we have moved from the 20th century into the new millennium. This is a story for anyone who is interested in understanding the ways that we have changed, and the ways we haven't really changed at all - even though things look very different than they did 80 years ago. This is a quick, compelling read that transports the reader into the charm and challenges of a world that is now gone, but that still offers us much to think about today.

FOREWORD

You may not know Vincent “Vince” Marando, but you would be glad if you did. Vince looks a bit like Tony Bennett, he’s lots of fun, and he’s a heck of a good cook. He’s a great guy to spend an evening with – you’ll eat good food, drink good wine, and have interesting conversation.

But that’s not why you should read this book.

This book will let you begin to know Vince Marando – and in getting to know Vince Marando, you’ll get to know America a little better, too. And you will get some insight into how much – and how little – the U.S. has changed over the course of the last 80 years.

In this volume, you will read about what Vince calls the “long decade” of the 1940s – from 1938 to 1952. The catalyst for Vince’s ruminations on his past and our crazy present was the release of the data from the U.S. Census of 1940. This is the first touchpoint connecting then and now – the Census was conducted in 2020, just as it was in 1940.

Of course, Vince was not even two years old when Gertrude K. Bunce, the 1940 Census enumerator, came to his home. So how does he remember this?

Vince was just 18 months old on April 4, 1940 when Gertrude Bunce, Census Enumerator, arrived at his family’s home. When the 1940 Census was released to the public in 2012 – listing the names of his family and neighbors – it allowed him to “almost” enter his world the way it was at that time. Vince started doing research on his family, his community, and the lives of those who raised him.

So, Vince began to write. And after he had been writing for a while, it became clearer that he was not just writing about his life, his past – he was writing about the intersection of our past, and our present. As the research progressed, he realized something: that little boy’s life spoke to so much of what is going on in our 21st century American lives. While on the surface it seemed like everything had changed, there was plenty that hadn’t changed, and much from that time that was coming to the forefront again.

It was quite fascinating: Vince’s life was interesting enough on its own, but as he wrote, more and more parallels between the 1940s and the 21st century became evident. Exploring the ways that the past and the present were shedding light on each other became not only easy, but virtually unavoidable.

Take, for instance, immigration: Vince’s maternal grandparents and his father were all immigrants from southern Italy (specifically, Sicily and Calabria). In the 1940s, Italians were considered among the lower class of immigrants to the U.S. – and on top of that, Vince’s father came to the country illegally. Indeed, when Vince was a teenager the family spent three summers picking green beans and berries on a farm outside of Buffalo with other Italian immigrant families – work that is primarily done now by Hispanic immigrant laborers, who have taken up that lower rung on the immigration ladder as Italian immigrants have climbed higher.

Vince’s exploration of what it meant to be raised in an immigrant household in Buffalo in the 1940s suggests that not much has changed in the intervening years – immigrant families still tend to live in multigenerational households where the children speak more English than the adults in the family. Italian then, Spanish now… but English outside the home and native language at home continues to be the pattern. In addition, living conditions for many immigrant families still remain cramped; and immigrants generally have limited job opportunities that are largely defined by their network.

The parallels between the Italian immigrants of that era and the Hispanic immigrants of the present seem to offer a glimmer of hope that America will work through the toxicity that surrounds so much of the discussion of immigration today. But of course this won’t “just happen” – and it is hard to see how building a wall between us and our neighbors to the south will speed this process along. What is notable, though, is that the complex relationship between the “tired… poor… huddled masses yearning to breathe free” and Americans whose families came to these shores some time before the latest arrivals was not substantially easier in the time of Vince’s childhood than it is now.

What has most definitely changed is today’s access to information and our relationship to media: Vince didn’t have his own radio, and his family didn’t have access to a television until he was a young teen. His “screen time” consisted of going to the movies once a week. The newsreels of the era told him of Allied victories in the Second World War, which he and his friends turned into games children played – one team being the “America good guys,” the other being the “Nazi bad guys.” There was “us” and “them” – but the villains were not living in our country.

The depth of the difference between the ways that information was transmitted in the 1940s and the way this works now is highlighted in the constant bombardment of “Breaking News.” In the 1940s radio, movies and TV, with three networks, provided the news at 6 and 11PM – if you even had a televison. There were no 24 hour a day channels to remind young Vince that the government thought his father was a “problem” – or that suggested to him that he was less of an American because one of his parents had not been born in the United States.

And then there’s the question of privacy, which has also changed over the decades. Having no privacy in 1940 meant sharing a bedroom and one bathroom. Today, the lack of privacy is largely a digital phenomenon. Nothing is easily erased; photos and conversations remain available long after those who were involved have forgotten about their existence. This change in the understanding of what constitutes “privacy” – and other words whose meanings have changed across the decades – plays a central role in this book. The “generation gap” in communication has been a challenge for much of the last 100 years, and it isn’t going away.

But to only focus on the gap itself is to miss what has fallen into that gap – for example, today’s young people worry about their photos being misused, but do they even know that they are missing out on the kind of privacy that lets them make mistakes and learn how to fix them without parental intrusion? Does the lack of physical privacy in childhood make it more difficult for the younger generations to develop the discernment that lets them know when to ask for help, and when to tough it out alone? And how can that knowledge be gained if there is no recognition that it may have been lost?

Making those decisions and learning those skills was just a part of being a kid when Vince was a child, and he gives us many funny, compelling stories that highlight both the joy and the potential hazards of gaining this wisdom. Was it all worth it? That is for the reader to decide.

When we take the time to read about a time gone by, it is easy to romanticize it: things were “simpler,” people had more “common sense,” and the world was just better. Of course, that is just the view from our perspective now – it did not seem that way to the people living in that moment. Vince takes the time to explore this phenomenon in various big and small ways throughout this volume. From reflecting on the different parts of Buffalo he became exposed to as he was growing up, to considering how federally-subsidized housing in his childhood neighborhood did not have the stigma it has now, Vince highlights how “common sense” isn’t really all that common – it’s just a function of growing up in a particular family, in a particular place, at a particular time. And he suggests that the idea of common sense is going to seem to fall apart for most everyone at a certain point.

This is an important insight – because it takes the idea that there was something that was fixed and shared and real and that is now gone, and says we need to reconsider that. Common sense is not something that we had and that is now lost, taken away from us somehow by someone or something.

Indeed, Vince seems to suggest that common sense is a function of being a child – and it is time for us to grow up. And by that I don’t just mean we need to grow up as individuals; in reading the stories Vince lays out here, I would argue that it becomes clear that it is time for us to grow up as a nation – to stop whining because our world is no longer the simple world of a child. It’s time for America – all of us – to stand tall and figure out what it’s going to take to live effectively in the current reality. Yes, the world is chaotic. People see things differently and in ways that will often make no sense from our own perspectives. But it is our job as adults (and as an adult nation) to take this in not with anger, but with the understanding that our “common sense” looks just as crazy to someone else as theirs does to us.

But Vince also makes an interesting and quite subtle point in discussing this: the “common sense” given to children in families is a foundation, and if that foundation is smashed too soon or too fast, that can create its own problems. In these musings, we see how the “common sense” of the Marando/Gardo families starts to come apart in pieces and over time: Vince sees a friend take money out of the church offering envelope to buy potato chips for himself; he sees another friend throw out the meat in a sandwich; he meets swimmers who...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.11.2021 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-0101-5 / 1667801015 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-0101-8 / 9781667801018 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,6 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich