Richest Soil Grows the Deepest Roots (eBook)

194 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-0983-8948-2 (ISBN)

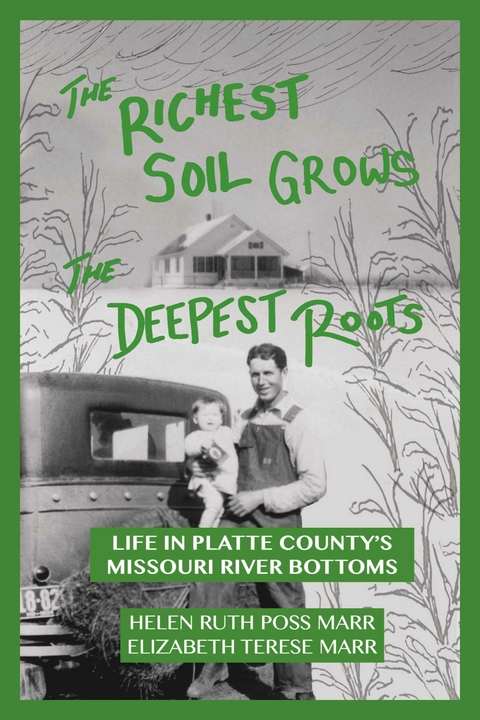

"e;The Richest Soil Grows the Deepest Roots"e; is a compelling historical memoir that intertwines Ruth's memories growing up on her family farm in the Missouri River bottoms of Platte County during the Great Depression and World War II with her family saga spanning five generations. Ruth's story gives rich personal insight into the complex intermingling that occurred in Missouri among Southerners who had been traveling west since the founding of Jamestown and mid-nineteenth century immigrants from Germany. Whatever the differences, Ruth's ancestors found much in common as hard-working people building a farm community in the fertile Missouri River Bottoms. This insightful book shares rich details about the region's history and its complexities. Meandering, treacherous, and full of sediment, the Big Muddy, as the river is called, has been a central feature of Ruth's family for over 200 years. From 18th century Boonsborough Kentucky, to the California Gold Rush, and the brutal Civil War in Missouri, readers will be enlightened by the rich history and deeply unique experiences shared in this memoir.

1

A Letter in the Basement

The basement of our antebellum home on Market Street in Weston, Missouri, was stacked with newspaper clippings, photographs, letters, old tools, antiques, and memorabilia. These were the accumulation of several generations documenting life and business dealings in the historic town. Transformed several times since its founding in 1837, the little community was once central to life along the Missouri River in Platte County. Both my husband’s and my ancestral roots stretch back in this area five or more generations.

Weston is the hometown of my husband, Mike, whereas I grew up on our family farm about ten miles south. My childhood home was in the Missouri River bottoms of Lee Township. A river bottom isn’t really the bottom of a river but rather the low-lying land that borders it. In the case of the meandering Missouri River, the river bottoms are wide swaths of fertile land created as the river shifted course over time carving deeper between two sets of bluffs.

Now on the National Register of Historic Places, Weston was an important steamboat port during its peak years leading up to the American Civil War. In St. Louis, ships would load up with passengers and supplies for the trip up the Missouri River, stopping at ports along the way, Weston’s landing being among them. Several trails important to westward expansion originated nearby, including the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe trails. Just across the river from Weston was (and still is) Fort Leavenworth. During westward expansion, soldiers from Fort Leavenworth protected wagon trains hauling supplies on these trails. On the return trip, the ships—emptied of their up-river passengers and cargo—would stop again at Weston to load up with timber and animal pelts as well as hemp and tobacco. These two crops were grown just outside of town on undulating lands that had been cleared of timber. The hemp would be made into rope and delivered downstream for cotton baling.

Weston’s importance to transportation and trade was not to last, due to nature, war, economics, and technology. The river, which was critical to the town’s commerce, was fickle and dangerous. In 1858, the Missouri River flooded and moved the channel, holding up steamship business for months (Chiaventone, 2012). As railroad transportation began to displace river transit, Kansas City and St. Joseph grew, while Weston languished, though a connector rail line brought some relief. The Great Flood of 1881 caused the river to change its course, shifting about two miles from town, leaving Weston completely landlocked.

The American Civil War was particularly brutal near the border of Missouri and Kansas, and Platte County saw its share of conflict. The aftermath of the war caused the population to decline significantly. Some families left during the war and didn’t return. African Americans’ freedom from the amoral brutality of slavery meant many economies dependent on human bondage had to adjust to new terms. For Weston, the local labor-intensive hemp economy, reliant on slaves, virtually ceased after the war, as did tobacco production the last four decades of the nineteenth century. Adding to Weston’s challenges were two major fires, in 1855 and 1890, which all but burned downtown Weston (Chiaventone, 2012).

Despite the repeated setbacks and population decline, area farmers began growing tobacco again at the turn of the twentieth century, and Weston renewed its tradition as a sizable loose-leaf burley tobacco market boasting the only auction houses west of the Mississippi River (Clayton, 2020). Today, the tobacco market no longer exists, and tourism is the primary economic driver with visitors enjoying the town’s history, featuring a charming downtown, shops, restaurants, antebellum homes, and the Holladay Distillery. Because Weston’s heyday occurred before the Civil War, many original structures have been preserved, including the three-room abode on Market Street where Mike and I retired.

•••

The old brick house—built in 1849 on land once owned by Elijah Cody, a local hemp house proprietor who was William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s uncle—came into our possession by way of family. Mike and his twin brother, George Patrick “Pat” Marr Jr., inherited the property from their mother, Eva Marie “Tudy” Marr (née Berntsen), when she passed away in 1977. Though we were still living in Wheaton, Illinois, Mike bought his brother’s claim to the property soon after Tudy’s death. At that time, we began planning our eventual retirement back to our family roots in Platte County.

Widowed, Tudy had bought the house in the late 1950s, after seeking advice from her sons about the possible purchase. She borrowed money from her father, John Berntsen, to make the down payment. Extending even earlier than Tudy’s purchase of the property, I had my own family connection to the home. An aunt, Maud Barton Poss, had been living at the house since my childhood. Before I was born, she married my dad’s oldest brother, Frank Anton “Tony” Poss. They had a son (my cousin Barton), but then divorced. Maud was the granddaughter of David Holladay and the grandniece of Ben Holladay, the “Stagecoach King.” Ben Holladay made and lost a fortune establishing a transportation empire that included a successful network of stagecoach lines crisscrossing the western United States during the mid-1800s (Frederick, 1940). Among the Holladay brothers’ numerous business dealings was Weston’s Holladay Distillery, which they founded in 1856.

Aunt Maud and Tudy were friends, and both were members of Weston’s Holy Trinity Catholic Church just a few steps up the hill from the house. When Mike and I married in 1957, Aunt Maud was thrilled our two families had joined. After our wedding mass at Holy Trinity, she said to me, “This is the happiest day of my life!”

When Tudy purchased the home, she let Maud continue to live there because my aunt was elderly and lacking resources. Uncle Tony had passed away, and even when he was alive, he was not much help to Maud. Barton, too, was deceased, as were Maud’s two brothers. Maud died in 1961, after several weeks in the hospital. Following her death, Tudy renovated the home, but until then, the structure had no indoor plumbing or electricity. Thus, the outhouse was still in use. Going to the privy required descending a long set of rickety wooden stairs at the back door or walking out the front door and around the house.

To say Maud and Tudy were enthusiastic about local history and antiques is an understatement. Both held on to precious family heirlooms and assorted documents. In my estimation, there was more than a bit of hoarding that occurred, but Tudy would say, “Don’t touch those stacks; I know where everything is!”

With Maud’s family history, one can imagine all the Holladay-related artifacts Tudy found in the house after Maud’s death. Maud had no heirs, so Mike’s mother donated many of her historically significant relics to the Weston Historical Museum. After Tudy passed away and we took possession of the house, we continued to discover other items, which we, too, passed on to the museum. Here and there, we would also find little notes and correspondence Maud had written about her family history—that apparently being her most precious possession in later years. Along with her genealogic interest, she saw that Weston had a unique history worth preserving. Maud was a founding member of the Platte County Historical Society, and her collection of Holladay-related photos, correspondence, and business records, along with Plains Indian relics, made the house feel like a museum, in and of itself.

•••

Before Mike and I renovated the property, the basement space was dark and musty with a dirt floor. For years, it seemed, we brushed away dust and cobwebs as we dug and sorted through stacks and boxes. When our children were growing up, we would stay at the house (then Tudy’s) for our annual summer visits with family. Our kids thought the basement was full of copperhead snakes and spiders. By the time we moved into the house in 1990, our children were grown, getting married and starting to have little ones of their own. The basement was an endless source of fascination to children and adults, alike. There were treasures to be found—or at least some local history.

One day while searching through Maud’s belongings in our dank basement, I came across a letter that would forever change my understanding of my parents and their relationship. The correspondence, written August 10, 1928, was from Maud to her son Barton. Maud addressed the letter to “Barton Poss, CMTC, Company F, Seventeenth Infantry, Fort Des Moines, Iowa.” Barton was away at Citizen’s Military Training Camp (CMTC). Upon his return home, Barton must have brought his mother’s letter with him, and she had saved it.

CMTC, which occurred every summer from 1921 to 1940, was part of the US National Defense Act of 1920 and a compromise to mandatory military training. At the height of CMTC during the late 1920s, 40,000 young men attended camp in about fifty different locations throughout the country (Kington, 1995). Created to promote good citizenship and, more importantly, to support the country’s national defense, the month-long camps for young men aged seventeen to twenty-four heavily emphasized physical activity and sports.

My cousin Barton Poss.

Sixteen at the time, Barton was under the minimum age and seemed to be struggling with camp life. He must have complained about the rigors in earlier...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.9.2021 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-0983-8948-4 / 1098389484 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-0983-8948-2 / 9781098389482 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,0 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich