CHAPTER 1

Earning our Caps

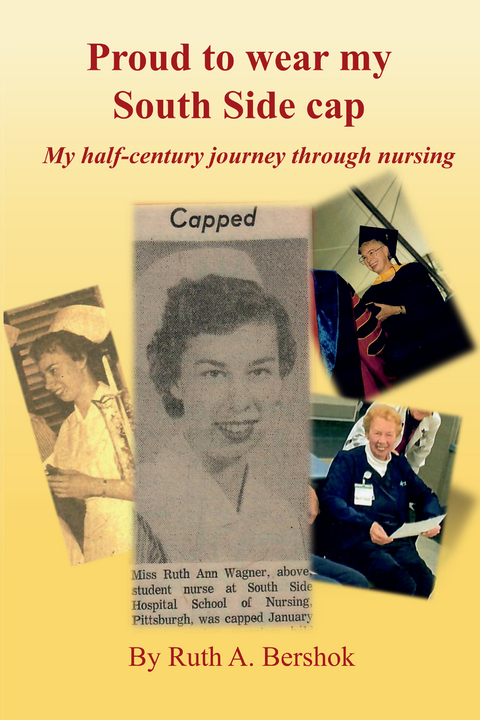

It was mid-summer 1958, and the strong afternoon sunlight highlighted the age of the old brick building that would be my home away from home for the next three years. My father had driven me to South Side Hospital School of Nursing in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, about 25 miles from my hometown of Canonsburg. The program was year-round for a full 36 months. We parked on the sidewalk adjacent to the nurses’ residence; there were no hospital grounds. As my father pulled my suitcases from the car, I observed the other students walking the steps to the entrance. Like me, most were dressed in heels and calf-length skirts. My father carried the suitcases up the stairs and placed them before the receptionist’s desk in the entrance area. When an upper-level student came to escort me to my room, my father and I said our goodbyes. My father could go no further, even to help me with my luggage; no men were permitted past the receptionist’s desk—Rule #1. As I would soon learn, there were many rules here.

My father was very proud that I was going to be a nurse and was happy to let people know of my selected career. He would tell everyone he met. Once, when I was a senior in high school, my father was in the hospital with a heart condition. I was visiting him when the doctor came in to do an EKG. The doctor recommended that I leave while he performed the procedure. It was my father who spoke first. “She’s going to be a nurse. Can she stay and watch the procedure?” The doctor smiled. So, I stayed while he good-naturedly explained step by step the procedure as he performed it. I carefully observed my first lesson in the medical field.

However, I have be to honest. Nursing was not my first career choice. When I was in grade school, one of my neighbors was a teacher. She let me help her prepare her classroom before the school season. I loved to do this. I would sharpen yellow pencils, organize books, decorate the classroom, and do whatever else she needed done. Once, I asked her for a few old books that were being thrown out. She obliged, and I used them to teach my dolls and stuffed animals. I held classroom in my attic playroom. Using boxes, I made chairs for my class. Each doll and animal had its own seat facing me. I had about eight “students.” With the books my neighbor gave me, I read to the students. I asked them questions, and imagined their hands raised. “Miss Wagner! I know the answer!” I corrected the students when needed. I’m sure I held a hundred classes in that small attic room.

I was about fourteen when I realized that my dream of being a teacher was not likely to materialize. My parents did not have the financial resources to pay for a college tuition. My mother was a store clerk at a dress shop near our home. Her salary was minimal. The store owner tried to offset the low wage with discounts on clothes. My mother had magnificent hats and gloves beyond her economic status. My father was a painter by trade, but heart and lung conditions eventually prevented him from climbing ladders, so he took a janitorial job while I was in high school. From my view as a teenaged girl in the mid-50s, I had only a few choices for career: teacher, nurse, secretary, store clerk.

With my father frequently in the hospital, I would observe the nurses who attended him. After I realized that teaching was not a viable career option, I became curious about the nursing field. I watched the nurses use their skills to benefit the patients, to help make them comfortable, to improve their conditions. It appealed to me. One of the members of my church was a student nurse at South Side Hospital. I asked her all about the nursing program there. She gave a positive response. She told me South Side was a great hospital to train at; students get a lot of practical experience. I was encouraged. At that time, the three-year nursing school programs were a lot less expensive than a university degree. Later, I realized why this was. We student nurses spent at least half of our program time working in the hospital associated with the school; we provided valuable labor. Yet, even with the lower costs, I knew my parents still did not have the money to send me to nursing school. The summer before my senior year of high school, I discussed the issue with them. At first, they said, “We’ll have to see.”

I knew my father would advocate for me. My father and I were close. I was the youngest of three children, and the only girl. There was a ten-year gap between my oldest brother and me, and a six-year gap between my second brother and me. During my teenage years, I was the only child in the house. I was daddy’s little girl, and my father wanted me to be able to follow my dreams. It was about a week before my parents gave me their answer. During the wait, I had thought of other options to pay for nursing school, such as working as a store clerk until I had saved enough money. I was relieved and happy when my parents told me that they could send me to nursing school. They had made the very difficult decision to cash in their life insurance policies to pay for my tuition and books. Given my father’s medical condition, I knew this was a genuine risk and a sacrifice. This inspired me to do my best. Shortly thereafter, I started the application process.

And, thus, here I was in the late summer of 1958, unpacking my belongings in the student nurses’ residence. We each had our own small room, consisting of a single bed, a dresser/desk combination, a chair, a bedside table with a lamp, and a closet. The bathroom and showers were down the hall. There were no personal laundry facilities. The school washed the students’ uniforms. Anything else we wanted to wash was usually done on our frequent trips home, or in the bathroom sink. Most of the girls, including me, washed their hosiery in the sink. The classrooms and the hospital’s dining room were in the same building. The school nurse also had an office in the residence building. Due to the nature of our work, the school wanted to be sure we were healthy. Each month, we had to weigh-in and speak to the school nurse. The residence building was connected to the hospital via an inside staircase. We could go from our dorms to the hospital without going outside.

After I unpacked, I met with my classmates. There were 26 of us starting the program that year. An upperclassman gave us a tour of the building. I learned a few more rules, many of which I was not expecting. For example, students must remain single throughout the nursing program. Marriage would result in disenrollment. Pregnancy also earned an automatic disenrollment. Further, if we left the building to go anywhere, we had to go in pairs. After I experienced the neighborhood, I agreed with that rule. Also, we were not allowed to leave the residence wearing pants; it was not considered ladylike. I did not agree with this rule. Still, we only broke it on rare occasion, and only when it was bitterly cold outside. Our “house mother,” a regimented but caring woman in her early 60s, said, “Now girls. If you put on a pair of pants under your skirt and roll them up, I won’t see them. When you are out of sight of the hospital you can roll them down. Just make sure you roll them back up before you come back in.” We were grateful that she allowed us this minor rule infraction. Another rule was lights out in our rooms by 11 p.m. The house mother made rounds between 11 p.m. and midnight. She would open our doors, which were always unlocked, and verify each student was in bed and the lights were out. The house mother’s name was Mrs. Patterson. Unbeknownst to her, we called her Mrs. Pittypat, because we could hear her walking up and down the hallway each night.

We wore our uniforms both to class and while working in the hospital. The color of the dress distinguished the year of the students. Thus, a doctor or nurse in the adjacent hospital where we did our clinicals would know a student’s level simply by the color of her dress. First-year students wore blue and white stripes; second-year students wore solid blue; and third-year students wore pink. All students, with the exception of students in the first six months, wore a cap. All students also wore a white bib and apron over the dress. The instructors told us how to keep our apron from getting wrinkled as we sat in class. We had to fold the two sides of the apron in our laps. We also wore white hose and white nursing shoes. Our shoes had to be polished and shoelaces clean at all times. When the Director of Nursing passed students in the hallway, she would quickly look us over up and down, inspecting our appearance. Students found her intimidating. When I saw her coming down the hallway, I would cringe inside. I had never seen her smile. If she felt some aspect of a student’s uniform was not up to par, she would stop the student and crisply direct her to remedy the flaw. We soon began warning our fellow students when she was in the vicinity. Her severity won her a place in a camaraderie song that upper-class students taught us. To the tune of The Caisson Song, the students sang, “We are brave; we are bold; and the whiskey we can hold is a story that’s never been told. . . . And if Logan should appear, we’ll say, ‘Helen have a beer!’ In the cellars of old SSH.” There were many songs we learned and sang at South Side.

For the first three months of the program, we had full days of classes, no clinics yet. After dinner, we had study time . . . until 11 o’clock of course. On more than one occasion, I was caught by the house mother for...