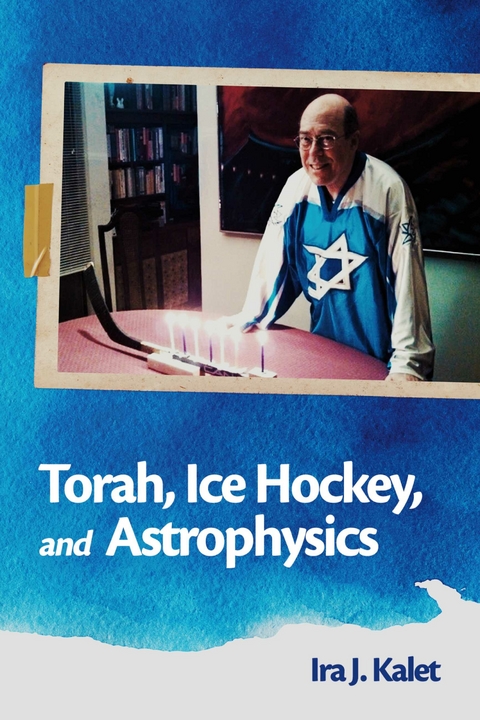

Torah, Ice Hockey, and Astrophysics (eBook)

184 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-0983-4627-0 (ISBN)

This book contains Ira's stories about growing up in the sputnik era, a unique time in our nation's history where science was richly funded and exciting new ideas in physics were developing. Ira also wrote a series of essays weaving the ideas of ice hockey and physics into the weekly Torah portion. Ira completed a draft of this manuscript only a few days before his death. It represents his thoughts about Torah from a unique perspective and the values and ethics he wanted to leave as a legacy. He broadened "e;Astrophysics"e; to include all of physics, and mathematics and computing as well. Not every chapter has something on all three topics, but you may find a connection of which he was not aware. Some chapters are transcripts of Torah commentaries (divrei Torah) that he was privileged to give at local synagogues in the Seattle area, along with some additional explanatory material. Some are accounts of thought-provoking experiences. Perhaps you will be inspired to write your own. There is much more to learn.

Cornell

After I was admitted to Cornell, my parents took me there for a few days to get acquainted with the campus and its people (yes, later to become “my people”). The campus sprawls over a large hilltop above the City of Ithaca, New York, and above Lake Cayuga, 38 miles long, the longest of the five “Finger Lakes” of upstate New York. Although New York City was well known throughout the world, the rest of New York State was (and likely still is) unfamiliar to most. It is very rural, with large forests and old mountains, not high even by Washington Cascades standards, but prominent and largely uninhabited. Much of upper New York State is actually a state park, Adirondack Park. This park is the largest state park in the, U.S., and also is larger than any of the U.S. national parks in the “lower 48” states.

The University was founded by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White in 1865, as a New York State Land Grant institution as well as a privately endowed institution. Ezra Cornell’s motto, “I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study” is on the University’s official seal.

The diversity of organizational units and fields of study were unparalleled at the time. By the 1960s, the Cornell Mathematics and Physics departments had achieved the highest status and recognition in those fields. It was thrilling to read of all the different course offerings, and to see who was teaching them.

I confess to being a little intimidated too, but I got over it. Aside from the spectacular physical beauty, I enjoyed the exposure to students studying agriculture, home economics, industrial and labor relations, hotel administration, and of course the usual collection of traditional Arts and Sciences.

Cornell’s Engineering College had a quadrangle that radically departed from the traditional “College Gothic” style. The Engineering buildings looked like giant toy boxes, with huge uniformly colored panels, each color corresponding to a different department. The Mathematics department was a more standard “College Gothic”, located on the Arts quadrangle (the “Quad” for short). Just walking from one class to another or to the libraries was a significant exercise. In the Spring and Fall it was a walk through a visual paradise. In the Winter, it got so cold, there was ice (or snow) on the walkways all winter. Despite having layers of real winter coats and warm clothing underneath, we often had to stop and enter an intermediate building between our starting point and destination, in order to thaw out.

The College of Agriculture maintained a working dairy which supplied milk, cream, butter and eggs to the campus food services. There was also a Veterinary College, and large animal facilities. In addition to the usual intercollegiate sports, Cornell had a polo barn for indoor polo. I went to one of these polo matches, and it was terrifying to see these huge horses running in such a confined space making tight maneuvers as demanded by their riders. A good experience to have once.

More exciting than the polo barn was Lynah Rink, a beautiful ice rink with seating for spectators to come to Cornell varsity intercollegiate ice hockey games (Eastern College Athletic Conference, or ECAC, not Ivy League). But better than watching, the rink had public skating sessions, and a “learn to play ice hockey program” through the Intramural Sports division. I had been on ice skates twice before that but I signed up, bought some basic equipment, and the Intramural program provided the rest. I was a math and science geek but no one seemed to mind.

Cornell Scramblers

In the Spring, I enrolled in a German literature class, a real struggle for me. I had no patience to do translation on my own, and insufficient knowledge of vocabulary and grammar to read fluently. However, I was reading an assignment, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s “Novelle,” chapter 1, while sitting at the top of Library Slope on a beautiful Spring day, and came upon the following sentence: “hierauf nun steht gemauert ein Turm, doch niemand wu¨ßte zu sagen, wo die Natur aufh¨ort, Kunst und Handwerk aber anfangen.” It was the first sentence I could translate without consulting my German-English dictionary. “Ahead, a man-made tower stood, but one could not really say where Nature left off, where art and craft began.” And as I lifted my head from the book, looking down the vast grassy expanse of Library Slope, past the trees, the old Cornell men’s dormitories came into view, a chain of classic college gothic style stone structures: McFadden Hall, Lyon Hall, a covered walkway, and finally, Baker Tower.

The Baker dormitories were built in 1928 and the years following. I lived there twice during my undergraduate years, once in Baker Tower, and once in Lyon Hall. The rooms are well insulated (the buildings are thick stone) and well heated, providing a refuge through the cold and snowy Ithaca winters. In those days, the rooms did not have private telephones, and cellular telephones did not exist. There were only shared wall telephones in the hallways. So we got to know our dormitory neighbors by answering the telephones, as well as just through normal proximity. Classmates lived nearby, and we often worked together on homework assignments. Physics and mathematics being somewhat esoteric subjects, we also shared a lot of “in” jokes which would make no sense if you did not understand physics. One friend, Max Mintz, was studying electrical engineering, and shared a lot of classes because of the overlap of this area with physics. So we all knew Maxwell’s Equations, the four basic laws of classical electricity and magnetism. Partly from the name, and partly out of admiration for the beauty, symmetry and universality of these equations, Max often insisted that any problem could be solved using them. So one day I suggested to Max that we had a physical problem here in the dormitory that could not be solved by Maxwell’s equations. It was the fact that the telephone in the hallway rang at all hours and woke people from their much needed rest. He responded, “Of course this can be solved by Maxwell’s equations. I will show you.” He took a piece of paper, wrote the equations on it, took a screwdriver and opened the telephone box. Then he crumpled the paper, stuffed it between the clapper and the bell, and indeed our problem was solved.

Above: The main residence building, Ms Kalbfeisch’s home, served as our quarters. It was really comfortable; I enjoyed many evenings reading Plato’s dialogues in the living room when I needed a break from radio astronomy.

August Kalbfleisch

Summers for college students have always been challenging times. Most of us needed to earn some money toward the cost of the following year’s education and living expenses. It was certainly possible to find a job in the commercial world, doing relatively mundane tasks for a minimum wage, but there were also a few opportunities, especially for science and engineering students, to actually learn on the job, a kind of science apprenticeship, or Summer Scholarship. Of these, the most exciting were the ones that involved participation in research projects. I had the good fortune to participate two summers in one such program.

Somehow I learned of a program run by the American Museum of Natural History Hayden Planetarium, supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation. It had been made possible by a gift to the Museum from August Kalbfleisch in her will. She owned a 94-acre plot of land in Dix Hills, Long Island, near Huntington. This land was relatively undeveloped and had large tracts of woods, open fields, a large main residence, a carriage house with rooms upstairs, originally probably a resident caretaker’s quarters, and a single family home at the entrance gate. The Museum established the Kalbfleisch estate as a field research station, where Museum staff could conduct field studies. Dr. Wesley Lanyon, a curator in the Ornithology Department of the Museum, served as the resident director, and lived in the home at the entrance with his family. In addition, the site hosted a radio astronomy project, directed by Dr. Kenneth L. Franklin, of the Hayden Planetarium. and several field biology projects run by Museum staff. Each Summer between 9 and 12 students were selected from among a pool of applicants, to participate in the various projects. I was selected to work on the radio astronomy project for the Summers of 1962 and 1963.

We students lived in the main estate building, which had an ample dining room, living room and study downstairs, and several small and large sleeping quarters upstairs. The largest rooms were arranged as dormitories, and a few students had private quarters, in particular the one female student participant each of the two summers I was there. A full time housekeeper came in each day to cook our meals, and take care of other house chores. We helped the housekeeper, but there were no assigned tasks; it was done on an informal basis, almost like and extended family.

Dr. Lanyon had two students who worked on bird banding, field observation and other ornithology projects. One evening he did a taxidermy demonstration, which at first was jarring, but at the end, the specimen was so perfectly preserved, it was really amazing. Other projects involved plant biology and ecology, study of small mammals in their natural habitats, and herpetology projects.

...| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.2.2021 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-0983-4627-0 / 1098346270 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-0983-4627-0 / 9781098346270 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 11,1 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich