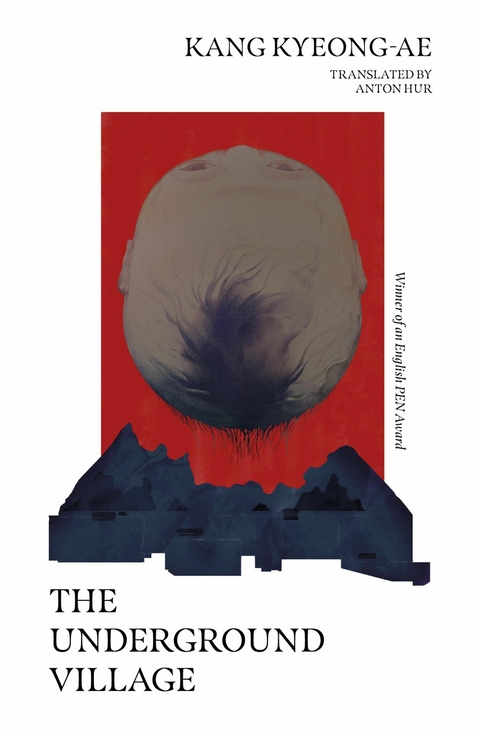

The Underground Village (eBook)

304 Seiten

Honford Star (Verlag)

978-1-9997912-7-8 (ISBN)

Kang Kyeong-ae (1906-1944), one of Korea's great modern authors, wrote her stories during the Japanese occupation of Korea.

One of the things which makes Kang Kyeong-ae (1906-1944) unique among Korean women writers of the era, most of whom lived in the cultural hub of Seoul, is that all her prose fiction was written in Jiandao in Manchuria, China. Although it was on the periphery of Korean literature, Jiandao was at the time the centre of an armed struggle to overthrow the Japanese colonial rule of Korea (1910-1945). This meant that while most other authors in Seoul also worked as reporters for magazines or newspapers and were central members of literary circles, Kang had vastly different preoccupations. Living in Manchuria and devoting herself to literary creation imbued Kang with an artistic and political tension which enabled her to make a greater artistic achievement than any of her contemporaries.

*

Kang Kyeong-ae was born to impoverished peasants on 20 April 1906 in Songhwa County, Hwanghae Province, in what is now North Korea. However, following her father’s death and her mother’s remarriage, Kang grew up in Jangyeon County, also in Hwanghae Province. Although her stepfather had money, he was an elderly, disabled man, and Kang’s mother is said to have been a veritable servant to him. At around the age of seven, Kang taught herself to read hangul, the Korean alphabet, from a copy of the classic Korean novel Tale of Chunhyang (Chunhyangjeon) that happened to be in the house. She went on to read other traditional prose fiction in hangul, and elderly neighbours vied with each other to take her home to have her read similar works out loud, buying her sweets as recompense. The girl was thus given the epithet ‘Acorn Storyteller’ in her neighbourhood.

As a result of her mother’s pleas to her husband, Kang was able to enter primary school in 1915, already past the age of ten. The family was unable to pay expenses such as tuition fees and money for stationery, and Kang had to study while feeling ill at ease, even fantasizing about stealing her classmates’ money and possessions. In 1921, with help from her brother-in-law, Kang entered Soongeui Girls’ School (present-day Soongeui Girls’ Middle and High Schools) in Pyongyang. A Christian institution, this school was dubbed ‘Pyongyang Prison No. 2’ due to its strict dormitory regulations. In October 1923, during Kang’s third year, the students staged a class boycott in protest against both the strict dormitory life and the American principal who had banned ‘superstitious’ visits to ancestral graves during Chuseok, the mid-autumn full moon festival. Kang was expelled due to this incident, and she reportedly went to Seoul where she studied for one year at Dongduk Girls’ School (present-day Dongduk Girls’ Middle and High Schools).

While a student in Seoul in May 1924, Kang published a poem titled ‘Autumn’ (‘Ga-eul’) under the pen name of ‘Kang Gama’ in the literary magazine Venus (Geumseong). However, Kang soon withdrew from Dongduk Girls’ School and returned to her hometown of Jangyeon in September 1924. Back home, Kang found her mother impoverished and was tormented by the silent criticism that an intelligent student had come back without any accomplishments. As a result, Kang went to China and worked as a teacher for two years in Hailin, northern Manchuria.

Hailin in 1927-1928, during Kang’s sojourn, saw the Manchurian Bureau of the Communist Party of Korea (Manju Chongguk Joseon Gongsandang) expand their power after colliding with ethnic Korean nationalists represented by the New People’s Government (Sinminbu), and Kang would have directly witnessed the serious ideological and physical conflicts between the two groups. Life in Manchuria at this time was particularly ruthless due to the secret ‘Mitsuya Agreement’ between Manchurian warlord Zhang Zuolin and Mitsuya Miyamatsu, the head of the Bureau of Police Affairs in the colonial Government-General of Korea. This agreement promised monetary reward for those reporting ethnic Koreans who possessed weapons or were involved in anti-Japanese activism, and resulted in both Manchurian warlords and Japanese imperialists expelling or arresting ethnic Korean independence activists – nationalists and communists alike. Additionally, under the perception that imperial Japan was invading the area with ethnic Korean peasants as spies, Manchurian warlords persecuted ethnic Koreans, demanding they pay money and become naturalized citizens of China. In such a situation, ethnic Korean nationalists and communists often suspected and even killed each other, and the lives of many ethnic Korean peasants who had settled in the area were destroyed. It is in this context that Kang came to harbour communist sympathies and to maintain the belief that for poor Korean peasants there was no difference between compatriot landlords back in Korea and non-Korean landlords in Manchuria.

Leaving Hailin in 1928 and returning to her hometown of Jangyeon, Kang played a key role in the establishment of the local branch of the Society of the Friends of the Rose of Sharon (Geun-uhoe) in 1929, and she founded Heongpung Night School, an academy for children from impoverished families where she taught classes on literature and started writing fiction in earnest. This period was also when she met future-husband Jang Ha-il, a graduate of the Suwon College of Agriculture and Forestry who had been appointed to the Jangyeon County Office. Living far away from his wife, whom he had been made to marry at an early age, Jang had come to Jangyeon together with his mother and lived in Kang’s house as a tenant.

As a writer who was involved indirectly with KAPF (Korea Artista Proleta Federacio; Korean Proletarian Artists Federation), Kang would have been influenced by the ‘December 1928 Resolution’ – the decision adopted by the Communist International on the reorganization of the Communist Party of Korea. This document argued that the party must discard intellectual-centred organization methods, organize labourers and indigent peasants by infiltrating factories and agrarian villages, and isolate ethnic reformists. While many Korean writers criticized these methods and the document, Kang did not and was consistent in her political attitude.

Therefore, the essays that Kang published after her return to Korea from teaching in Hailin in northern Manchuria and after the ‘December 1928 Resolution’ exhibit a level of awareness completely different from that in the short sketch-like poems that she had published earlier. For example, in October 1929 Kang published a criticism of the popular author Yeom Sang-seop, who was dubbed a ‘centrist’ at the time, and in February 1931 Kang published a rebuttal of Yang Ju-dong, a self-styled ‘syncretist’.

As the romance between Kang and Jang progressed, the couple invited friends to a simple wedding ceremony before relocating to Longjing in Jiandao around June 1931. In Jiandao, Jang worked as a teacher at Dongxing Middle School (present-day Longjing Senior High School) and Kang started to publish her fiction while taking care of their home. Jang was a good reader, understanding Kang’s literary world, always being the first one to read her works, engaging in discussions, and providing advice. Indeed, he was a devoted husband who did his utmost to treat Kang’s chronic illnesses.

Jiandao in the early 1930s was a land of war. While the Chinese people engaged in a fierce movement against both feudal landlords and warlords, Japanese imperialists incited the Mukden (or Manchurian) Incident in September 1931 and established the puppet state of Manchukuo in March 1932, before proceeding with mass-scale operations to eradicate ethnic Korean independence fighters. In the process, many people lost their homes, families, and lives. To flee such chaos, Kang left Jiandao and returned to Jangyeon around June 1932, then went back to Jiandao around September 1933. Although she did travel to Seoul and Jangyeon from time to time, from this point she lived in Jiandao, maintaining the household while steadily publishing her fiction.

In 1939, Kang returned to Jangyeon for the final time because her health had started to worsen in the previous year. In the end, she died on 26 April 1944 due to aggravated illness aged thirty-eight.

*

The class consciousness that Kang embraced in Hailin and the atrocities and popular resistance that she witnessed in Jiandao became archetypal experiences for Kang’s literary activity. Though she produced nearly all her writing in Manchuria, she never mentioned the Japanese puppet state’s specious propaganda, for example slogans such as ‘concord among five ethnic groups’ (Han Chinese, Manchurians, Mongols, Koreans, and Japanese) and ‘paradise under royal government’ (rule by the puppet emperor of Manchuria). Kang’s works are instead infused with the desolation in people’s lives caused by the creation of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, the ruthless reality of being ruled by soldiers, and the strenuous efforts required to protect one’s individual and social life against such forces.

Kang’s early fiction gives insight into the lives of Korean peasants living in Jiandao who had moved to Manchuria because life in their home villages had become unsustainable, and how compatriot landlords back in colonial Korea and non-Korean landlords in Manchuria were equally oppressive. For example, ‘Break the Strings’ (Pa-geum; 1931) recounts how a young ethnic Korean couple tormented by family and romantic problems comes to devote themselves to the armed anti-Japanese struggle in...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.11.2018 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Anton Hur |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Klassiker / Moderne Klassiker |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | communism • Feminism • Korean literature • Modern Classics • Short Stories |

| ISBN-10 | 1-9997912-7-4 / 1999791274 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-9997912-7-8 / 9781999791278 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich