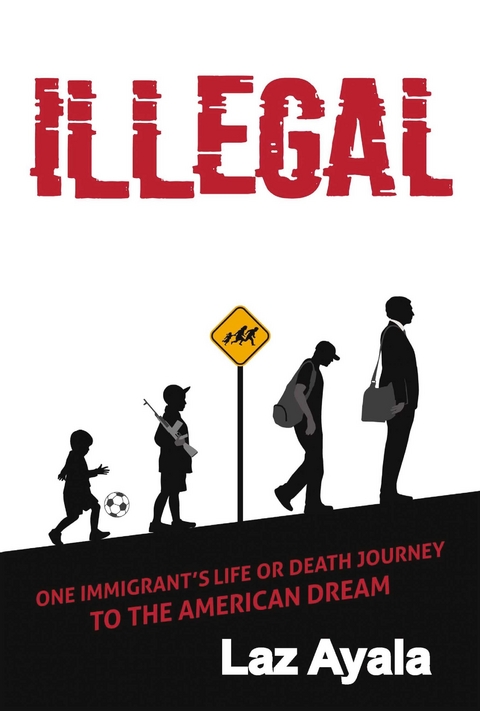

Illegal (eBook)

130 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-0983-1264-0 (ISBN)

Laz Ayala escaped war-torn El Salvador as a 14-year-old in 1981. He smuggled over the Mexican border into the United States curled up in the trunk of an old Cadillac. A new life waited in San Bernardino, California, with his Sister, father and brother. Laz had to succeed in school while learning English, with the threat of deportation looming. This is a story about immigration and the American dream. Today Laz is a successful real estate entrepreneur, developer, and philanthropist. From a Dreamer to living his dream, Laz Ayala tells the story about how he came to America, and his mission to humanize immigrants and reform immigration policy.

Chapter 1:

The Escape

If you go anywhere, even paradise, you will miss your home.

– Malala Yousafzai

(December 13, 1980. San Ildefonso, San Vicente, El Salvador.)

I’m awake early. It’s still dark out. I quietly pack what I can in a bag. I load my life into one duffel bag and get ready to leave San Ildefonso—the town where I was born, where my mother lived, died and is buried, where my friends and family live, where the mountains rise on two sides and the air is warm and damp .

I’m 14 and running for my life.

I can’t remember noticing the smells of fruit and the shadows of mango trees until now, the morning when I realize wherever I wind up, it won’t be here—won’t be home. I never paid much attention to the things that made me feel safe and at home until I could imagine them fading. I wonder if I’ll forget them or never experience them again. Tears roll down my face. There’s no negotiating with the grief. My father, brother and I are leaving in a few minutes, to begin something and end everything. There’s no alternative. There’s no discussion, no bartering. It is life or death. Escape is our chance for survival. But we might die today.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. I know there will be a series of buses and then someone will smuggle us into another country—a country I’ve never visited and where I know only my sister. Nothing about it feels normal or right. But then, nothing’s been normal or right for a long time.

My father and older brother stuff their last items into duffel bags.

There’s something deeply confusing about the caution and secrecy that surround our pre-dawn movements. It’s quiet and calm outside, with temperatures in the 80s and a light breeze. It’s another ordinary day. But I know my dad is trying to save us. I know I need to trust him. I saw what happened to the others.

Despite the calm, a feeling of dread comes over me. I want to stay in this moment of time. I want to stop all the clocks and stand here in the quiet for the rest of my life. I know everything will change, and I don’t want that. I want time to stop. I’m desperate to hold the seconds like an eternity. It never happened, it never happened. It’s not true. But no amount of wishing makes peace out of war or raises people from the grave.

I can hear voices from outside, voices I may never hear again. The hammocks we slept in stretch across the room, the blankets still warm. I hear the sleepy sounds of my town waking up—birds chirping, the rhythmic padding of hoofbeats as someone rides by. This morning there are no sounds of shots being fired, no shouting from the military bunkers, no bombs dropping.

For a few minutes I can forget.

I can forget the graffiti that first appeared two years ago—Bloque Popular Revolucionario (BPR), the tag of a group sprouted from the soil of Fuerzas Populares de Liberación (FPL). After many protests and demonstrations quashed by the military, they are fighting a long war against government forces. They started as Salvadoran educators and became revolutionaries. Then, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) began plastering graffiti on the walls. Everybody knew about the movement—kids and grandmothers, political and apolitical people. We all knew because it was all around us. But right now, in this moment, I can forget.

There were death squads on the ground and planes overhead. You could put it out of your mind at nightfall, but at daybreak, it all began again. It won’t begin again for me. I’m leaving today.

My brother nudges me forward. I don’t want to get on that bus. I know I can’t stay, yet I’m afraid to leave. My mind, my body and my breath are pushing and pulling in different directions. I’m trying to move but it feels like I can’t—until my brother pulls me hard while I’m looking back at our house of thatch and dirt floors. ¡Deja de Llorar! Todo estará bien. My brother orders me to stop crying. He says everything will be all right. I struggle to believe anything good can come from leaving. How can I know what’s next?

How do I know I’ll even survive the trip north to the United States, crossing the border crammed in the trunk of a car? Finally, I’m ready. I want that damned bus to get here. I just want to go. Yes, in the back of my mind, I want that bus never to come. I want the war to be over. I want it never to have started. But now I am resigned to following my father to a new life.

Before the El Salvadoran Civil War, I was a normal kid—school, girls, friends and family. We didn’t have much money but we went to school. My father worked in construction and we helped him. We played games in the streets. Each season brought a new game.

I remember it all in images and smells and moments in time. It’s beautiful and safe and free. We played outside every day after school; we roamed freely, before the war. Our house is small, and we got water the way most people do. I went down to the springs to wash clothes and bathe. I brought water back to the house and sometimes hauled up buckets to my dad to mix the mortar for various jobs. He paid me so I could have some cash. Lots of kids help their parents. We played soccer on the streets and made homemade kites, slingshots and tops. We played marbles one season and in another we invented games with cashews. After roasting them, we played with the shells—board games, counting games, invented on the spot in the patches of grass and on the roads in front of our houses.

Now I think about where I’m going. Will there be work? How will I contribute to my family if I’m not here collecting firewood for sale at the market on weekends? Will there be a trade day where I can get what I need or get something for my family? Will I still be able to help my dad? Will I earn money to get my own soda after work and school? Do they drink the same things, eat the same food? How will I talk to anyone? Do people even speak Spanish? And if so, do they speak it the way we do in El Salvador? How will I make friends? Do they play the games we do?

The memories of times gone by are bittersweet. We’re kids. We want to play and learn. But now it’s all about the war.

Those bloques established themselves in cities first, and then in small towns. It seems like everyone talks about the injustices of the government. There was a revolution brewing that began in cities like San Salvador. Propagandizing fliers were posted all around town. I didn’t know what that was all about. Then I began hearing people talk about the military and oppression. I started seeing protests on television. I tried to make sense of what was going on. I heard about older kids who left to join the movement and others who got picked up by the military, even boys my age. My dad told me, “Don’t go out. They’re recruiting today or tomorrow, so stay home.”

Things went from being interesting—even exciting—to creating a state of horror, terror and desperate fear. There was a lingering tension in the air. We watched and waited. We feared and prayed and tried to stay safe.

Many kids stopped going to school. People weren’t in the streets as much. When I did go out, sometimes I saw bodies getting dumped into the main streets from the death squads.

I began to understand there was a movement that went with the graffiti, a movement and a military response. I didn’t know why exactly. But I knew things were getting worse.

People from our town were captured and some disappeared. There are lists carried by the army’s soldiers, names of people suspected to be in the movement. If you’re on a list, you might never be seen again. My dad is on the list. We know it’s a mistake. My dad tries to explain that it’s another guy with the same name. Dad’s not in any movement. But no one listens.

There’s a new military base in our town. They’re taking over towns and villages—to protect us, they say. But they’re the ones picking up kids like me, training them to fight, and they’ve got the list of names marked for arrest, torture and death. I don’t have a mom. I can’t lose my dad, too. We’ve seen attacks from the revolutionary fighters, and it has developed into a full-blown war.

My dad and brother and I have been working hard on a big house. The owner, Vences Lago Zamora, is a bright, talented man and ex-military who turned guerrillero and left to lead in the revolution. Working on the house was a good job, but he stopped paying, so we stopped working. We were excited to have that big job, but that’s over now. That and everything else.

My mind is racing, thinking about the good things, normal things, and then how things have changed. I think about the people in town who were tortured and killed. I remember seeing burned bodies, bodies with missing teeth, fingers, toes or limbs, nails ripped off. I worried it would happen to us.

Maybe I want that bus to hurry now. Thinking about what has happened makes me want to leave.

My brother was picked up twice by the military. My dad had to cash in on favors to get him out. Everyone is fearful of the military....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.7.2020 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-0983-1264-3 / 1098312643 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-0983-1264-0 / 9781098312640 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,2 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich