Quest for Freedom (eBook)

752 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-0983-1969-4 (ISBN)

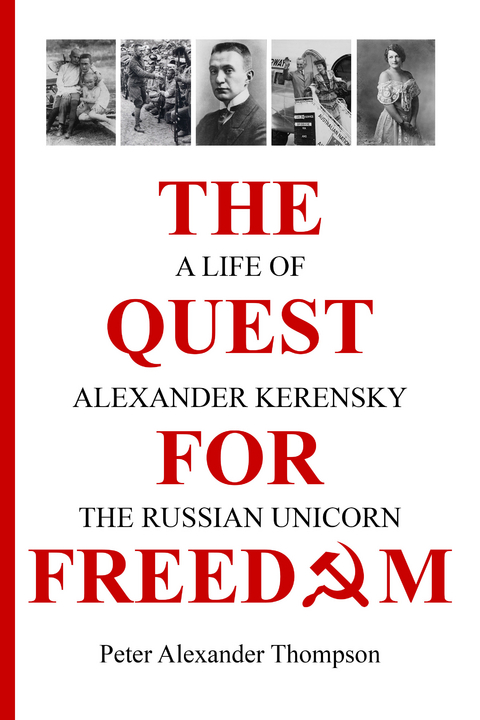

The Quest for Freedom, a biography of Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky published in June 2020, commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the death of the great socialist reformer who personified the Russian Revolution of February 1917 and yet who is remembered today, if at all, as 'the man who lost Russia'. In the first biography of Kerensky for more than thirty years, award-winning author Peter Alexander Thompson uses interviews with two of Kerensky's grandchildren, the Kerensky Family's private papers and Kerensky's own words to weave a compelling narrative that not only spans the entire revolutionary period but also covers World War I, the Russian Civil War and World War II.

Prologue

The Russian Unicorn

In the summer of 1963, a few months before the assassination of President John F. Kennedy at the hands of a pro-Soviet former United States Marine armed with a $19.95 rifle, an elderly man dressed for an earlier time in a three-piece tweed suit, his white hair cut in the style known in France as en brosse but which was popular in America as the crewcut, turned up at a party for newspaper and publishing people in the Manhattan apartment of Anthony Delano of the London Daily Mirror. ‘I forget who brought him and I didn’t know who he was,’ Tony Delano says. ‘He was introduced to me as Alexander Kerensky and he spent the evening sitting quietly in an armchair until it was time to go home.’1

Ah, yes – Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, the Socialist Revolutionary who personified the February Revolution, the great reformer who led the Provisional Government for one hundred days and who is best remembered today, if at all, as ‘the man who lost Russia’.

In 1963 Kerensky was in his eighty-third year, half-deaf, blind in one eye, his bearing slightly stooped, his complexion sallow from a kidney condition and needing his bone-handled walking stick to get around. All of these failings indicated decrepitude and yet, as the publication of his final book of memoirs showed, he was still capable of great passion.

At first hand he had witnessed the slaughter of liberty - the liberty that Marx cherished – under Lenin and Trotsky, and then, in exile, he had seen Stalin take the Soviet system to grotesque new depths. Reviewing Russia and History’s Turning Point (Duell, Sloan & Pearce 1965), Malcolm Muggeridge concluded, ‘Despite his years of exile, Kerensky remains indomitably and admirably a Russian democrat and patriot, embittered and infuriated, as well he might be, by the feebleness and asininity of many of those outside Russia who were nominally on his side.’2

Kerensky was living on the top floor of a redbrick townhouse at 109 East 91st Street, the home of Helen Simpson, widow of his great friend and political ally Kenneth F. Simpson, a United States Congressman and Republican leader of New York County. Survival had been a Pyrrhic victory. While Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin enjoy a global multimedia afterlife as historical celebrities, Kerensky has been reviled and is all but forgotten.

He was frequently reminded that it would have been easy for him to have retained power in 1917 had he betrayed Russia’s Allies in World War I and signed a separate peace with Germany, as Lenin did a few months later; had he turned a blind eye to the illegal seizure and partition of farmland instead of pleading with the peasants for patience until the necessary legislation could be passed; and, above all, had he executed Lenin and Trotsky for treason when he had the chance.3

Kerensky refused to take extreme measures to defeat the Bolsheviks and the consequences of that refusal proved irreversible until 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed under the weight of its own deficiencies. But, as the New York Times noted, there was a glimpse of forces at work during the Provisional Government’s brief existence ‘seeking to turn the vast land into a democracy, and to create a new society whose citizens would enjoy both freedom and prosperity’.4

Lenin’s genius was to transform Marxism into a fighting creed that had but one aim: total power. Instead of ‘peace, bread, land’ in a Communist Utopia, as he had promised, the Russians got civil war, starvation and seven decades of the most crushing autocracy of modern times.

In 2016 so many books were in production to mark the Centenary of the Russian Revolution in 2017 that it proved impossible to find a publisher for this one. Typical of numerous rejection notices, one leading British publisher wrote, ‘As publicity is so crucial these days, the fact that the Provisional Government failed makes it hard for us to make real claims for Kerensky’s place in history.’ This sort of evaluation isn’t unusual. Kerensky has no historic value today because the Bolsheviks destroyed the Provisional Government and smashed the Russian Republic he had established on 1 September 1917.

When the books were published, they invariably supported this view. Yet the fact that Kerensky failed in his mission could be viewed in an entirely different light: that it ranks as one of the greatest and most tragic misses of all time. The fact that his failure owed much to the hostility of Lloyd George, Balfour, Churchill and Clémenceau, and the indifference of Woodrow Wilson makes it even more imperative that he should be given a hearing today.

In his massive work on the Revolution, Leon Trotsky consigned Kerensky to his proverbial ‘dustbin of history’. ‘Kerensky was not a revolutionist,’ he said, ‘he merely hung around the revolution.’ Lenin was equally dismissive. ‘Kerensky,’ he sneered, ‘is a balalaika on which they play to deceive the workers and peasants.’5

The Marxist-Leninist view of Soviet hagiographers was that the Bolshevik Party had been at the vanguard of all three Russian revolutions: the ‘dress rehearsal’ of 1905, the overthrow of the Tsar in February 1917 and ‘the Great October Socialist Revolution’ later that year. Any historian who deviated from that line was denounced as a ‘bourgeois falsifier’.6 The Bolshevik influence in the 1905 Revolution was, in fact, minimal and neither Lenin nor Trotsky, much less Stalin, Zinoviev, Kamenev or any of the other ‘professional revolutionaries’, were anywhere to be seen when the Romanov Autocracy collapsed virtually overnight in February 1917 (Old Style).

Alexander Kerensky, a thirty-five-year-old member of the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian Parliament, seized the moment. As an excited crowd of revolutionary citizens and mutinous soldiers approached the Tauride Palace, the Duma’s home beside the River Neva, he shouted to his colleagues, ‘May I tell them that the State Duma is with them, that it assumes all responsibility, that it will stand at the head of the movement?’

Getting no coherent answer, he dashed outside and addressed the troops. ‘Citizen Soldiers,’ he cried, ‘on you falls the great honour of guarding the State Duma…. I declare you to be the First Revolutionary Guard!’

He had committed the Duma to the Revolution.7

By any standard, Kerensky’s hubris-inducing career in 1917 was phenomenal. As the Petrograd Soviet’s only member in the Provisional Government’s first cabinet, he was Minister of Justice (March-May) and in the second cabinet War and Naval Minister (May-September), then Prime Minister (July-August), Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces (August-October), and Minister-President (September-October).

‘There is no other statesman living whose accession to the Premiership would fill us with the same enthusiasm and hope,’ the Irish nationalist Robert Lynd wrote of Kerensky in the London Daily News in July 1917. ‘He is the representative of the world’s hope. With his defeat, the light of the world would go out.’

That light was indeed extinguished.

By definition the Provisional Government was a stop-gap measure to tackle Russia’s most pressing problems and, inevitably, those problems overwhelmed it. His grandson Stephen Kerensky says, ‘It is remarkable that the anti-Kerensky case made by politicians and historians, both in London and Saint Petersburg, is still founded on the idea that the Provisional Government should have solved all the social, political, economic and military disasters resulting from Nicholas II’s rule within six months of taking office.’

The biggest problem was the war. Attempting to revive morale in the Russian Army (and to aid Russia’s Allies on the Western Front) Kerensky planned an offensive for spring 1917. However, a power struggle between the government and the Petrograd Soviet delayed the start of the operation until 18 June, with fatal results for the Russian Army and the nascent Russian democracy.8

Then, as Prime Minister in August, Kerensky was confronted with a rightwing revolt from the Army’s new Supreme Commander, General Lavr Kornilov. It was Kerensky’s defeat of Kornilov’s forces with Soviet (and Bolshevik) help that fatally weakened his support among the military. When Red Guards and Baltic Fleet sailors attacked the Winter Palace on the night of 25-26 October, officers and soldiers alike sat back and did nothing as he was driven from office. Forced into hiding, he was lucky to escape with his life. Louise Bryant, an American journalist and a socialist, lamented his fall in her book Six Months in Red Russia:

I had a tremendous respect for Kerensky when he was head of the Provisional Government. He tried so passionately to hold Russia together, and what man at this hour could have accomplished that? He was never wholeheartedly supported by any group. He attempted to carry the whole weight of the nation on his frail shoulders, keep up a front against the Germans, keep down the warring political factions at home.9

So what had he achieved in those months? As Minister of Justice, Kerensky signed decrees that granted women full civil and political rights, including the right to vote, and established equality for all religions and ethnicities. This edict officially...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.6.2020 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-0983-1969-9 / 1098319699 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-0983-1969-4 / 9781098319694 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,4 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich