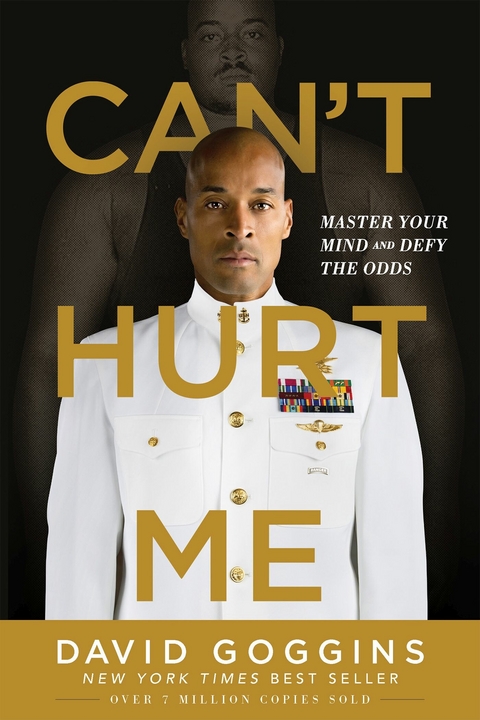

Can't Hurt Me (eBook)

200 Seiten

Lioncrest Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-5445-1226-6 (ISBN)

David Goggins is a retired Navy SEAL and the only member of the U.S. Armed Forces ever to complete SEAL training, U.S. Army Ranger School, and Air Force Tactical Air Controller training. Goggins has competed in more than sixty ultra-marathons, triathlons, and ultra-triathlons, setting new course records and regularly placing in the top five. A former Guinness World Record holder for completing 4,030 pull-ups in seventeen hours, he's a much-sought-after public speaker who's shared his story with the staffs of Fortune 500 companies, professional sports teams, and hundreds of thousands of students across the country.

New York Times Best SellerOver 5 million copies soldFor David Goggins, childhood was a nightmare - poverty, prejudice, and physical abuse colored his days and haunted his nights. But through self-discipline, mental toughness, and hard work, Goggins transformed himself from a depressed, overweight young man with no future into a U.S. Armed Forces icon and one of the world's top endurance athletes. The only man in history to complete elite training as a Navy SEAL, Army Ranger, and Air Force Tactical Air Controller, he went on to set records in numerous endurance events, inspiring Outside magazine to name him The Fittest (Real) Man in America. In Can't Hurt Me, he shares his astonishing life story and reveals that most of us tap into only 40% of our capabilities. Goggins calls this The 40% Rule, and his story illuminates a path that anyone can follow to push past pain, demolish fear, and reach their full potential.

Chapter One

1. I Should Have Been a Statistic

We found hell in a beautiful neighborhood. In 1981, Williamsville offered the tastiest real estate in Buffalo, New York. Leafy and friendly, its safe streets were dotted with dainty homes filled with model citizens. Doctors, attorneys, steel plant executives, dentists, and professional football players lived there with their adoring wives and their 2.2 kids. Cars were new, roads swept, possibilities endless. We’re talking about a living, breathing American Dream. Hell was a corner lot on Paradise Road.

That’s where we lived in a two-story, four-bedroom, white wooden home with four square pillars framing a front porch that led to the widest, greenest lawn in Williamsville. We had a vegetable garden out back and a two-car garage stocked with a 1962 Rolls Royce Silver Cloud, a 1980 Mercedes 450 SLC, and, in the driveway, a sparkling new 1981 black Corvette. Everyone on Paradise Road lived near the top of the food chain, and based on appearances, most of our neighbors thought that we, the so-called happy, well-adjusted Goggins family, were the tip of that spear. But glossy surfaces reflect much more than they reveal.

They’d see us most weekday mornings, gathered in the driveway at 7 a.m. My dad, Trunnis Goggins, wasn’t tall but he was handsome and built like a boxer. He wore tailored suits, his smile warm and open. He looked every bit the successful businessman on his way to work. My mother, Jackie, was seventeen years younger, slender and beautiful, and my brother and I were clean cut, well dressed in jeans and pastel Izod shirts, and strapped with backpacks just like the other kids. The white kids. In our version of affluent America, each driveway was a staging ground for nods and waves before parents and children rode off to work and school. Neighbors saw what they wanted. Nobody probed too deep.

Good thing. The truth was, the Goggins family had just returned home from another all-nighter in the hood, and if Paradise Road was Hell, that meant I lived with the Devil himself. As soon as our neighbors shut the door or turned the corner, my father’s smile morphed into a scowl. He barked orders and went inside to sleep another one off, but our work wasn’t done. My brother, Trunnis Jr., and I had somewhere to be, and it was up to our sleepless mother to get us there.

I was in first grade in 1981, and I was in a school daze, for real. Not because the academics were hard—at least not yet—but because I couldn’t stay awake. The teacher’s sing-song voice was my lullaby, my crossed arms on my desk, a comfy pillow, and her sharp words—once she caught me dreaming—an unwelcome alarm clock that wouldn’t stop blaring. Children that young are infinite sponges. They soak up language and ideas at warp speed to establish a fundamental foundation upon which most people build life-long skills like reading and spelling and basic math, but because I worked nights, I couldn’t concentrate on anything most mornings, except trying to stay awake.

Recess and PE were a whole different minefield. Out on the playground staying lucid was the easy part. The hard part was the hiding. Couldn’t let my shirt slip. Couldn’t wear shorts. Bruises were red flags I couldn’t show because if I did, I knew I’d catch even more. Still, on that playground and in the classroom I knew I was safe, for a little while at least. It was the one place he couldn’t reach me, at least not physically. My brother went through a similar dance in sixth grade, his first year in middle school. He had his own wounds to hide and sleep to harvest, because once that bell rang, real life began.

The ride from Williamsville to the Masten District in East Buffalo took about a half an hour, but it may as well have been a world away. Like much of East Buffalo, Masten was a mostly black working-class neighborhood in the inner city that was rough around the edges; though, in the early 1980s, it was not yet completely ghetto as fuck. Back then the Bethlehem Steel plant was still humming and Buffalo was the last great American steel town. Most men in the city, black and white, worked solid union jobs and earned a living wage, which meant business in Masten was good. For my dad, it always had been.

By the time he was twenty years old he owned a Coca-Cola distribution concession and four delivery routes in the Buffalo area. That’s good money for a kid, but he had bigger dreams and an eye on the future. His future had four wheels and a disco funk soundtrack. When a local bakery shut down, he leased the building and built one of Buffalo’s first roller skating rinks.

Fast-forward ten years and Skateland had been relocated to a building on Ferry Street that stretched nearly a full block in the heart of the Masten District. He opened a bar above the rink, which he named the Vermillion Room. In the 1970s, that was the place to be in East Buffalo, and it’s where he met my mother when she was just nineteen and he was thirty-six. It was her first time away from home. Jackie grew up in the Catholic Church. Trunnis was the son of a minister, and knew her language well enough to masquerade as a believer, which appealed to her. But let’s keep it real. She was just as drunk on his charm.

Trunnis Jr. was born in 1971. I was born in 1975, and by the time I was six years old, the roller disco craze was at its absolute peak. Skateland rocked every night. We’d usually get there around 5 p.m., and while my brother worked the concession stand—popping corn, grilling hot dogs, loading the cooler, and making pizzas—I organized the skates by size and style. Each afternoon, I stood on a step stool to spray my stock with aerosol deodorizer and replace the rubber stoppers. That aerosol stink would cloud all around my head and live in my nostrils. My eyes looked permanently bloodshot. It was the only thing I could smell for hours. But those were the distractions I had to ignore to stay organized and on hustle. Because my dad, who worked the DJ booth, was always watching, and if any of those skates went missing, it meant my ass. Before the doors opened I’d polish the skate rink floor with a dust mop that was twice my size.

Skateland, age six

At around 6 p.m., my mother called us to dinner in the back office. That woman lived in a permanent state of denial, but her maternal instinct was real, and it made a big fucking show of itself, grasping for any shred of normalcy. Every night in that office, she’d set out two electric burners on the floor, sit with her legs curled behind her, and prepare a full dinner—roast meat, potatoes, green beans, and dinner rolls, while my dad did the books and made calls.

The food was good, but even at six and seven years old I knew our “family dinner” was a bullshit facsimile compared to what most families had. Plus, we ate fast. There was no time to enjoy it because at 7 p.m. when the doors opened, it was show time, and we all had to be in our places with our stations prepped. My dad was the sheriff, and once he stepped into the DJ booth he had us triangulated. He scanned that room like an all-seeing eye, and if you fucked up you’d hear about it. Unless you felt it first.

The room didn’t look like much under the harsh, overhead house lights, but once he dimmed them, the show lights bathed the rink in red and glanced off the spinning mirror ball, conjuring a skate disco fantasy. Weekend or weeknight, hundreds of skaters piled through that door. Most of the time they came in as a family, paying their $3 entrance fee and half-dollar skate fee before hitting the floor.

I rented out the skates and managed that entire station by myself. I carried that step stool around like a crutch. Without it, the customers couldn’t even see me. The bigger-sized skates were down below the counter, but the smaller sizes were stored so high I’d have to scale the shelves, which always made the customers laugh. Mom was the one and only cashier. She collected everyone’s cover charge, and to Trunnis, money was everything. He counted the people as they came in, calculating his take in real time so he had a rough idea of what to expect when he counted out the register after we closed up. And it had better all be there.

All the money was his. The rest of us never earned a cent for our sweat. In fact, my mother was never given any money of her own. She had no bank account or credit cards in her name. He controlled everything, and we all knew what would happen if her cash drawer ever came up short.

None of the customers who came through our doors knew any of this, of course. To them, Skateland was a family-owned-and-operated dream cloud. My dad spun the fading vinyl echoes of disco and funk and the early rumbles of hip hop. Bass bounced off the red walls, courtesy of Buffalo’s favorite son Rick James, George Clinton’s Funkadelic, and the first tracks ever released by hip hop innovators Run DMC. Some of the kids were speed skating. I liked to go fast too, but we had our share of skate dancers, and that floor got...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.11.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5445-1226-0 / 1544512260 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5445-1226-6 / 9781544512266 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,0 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich