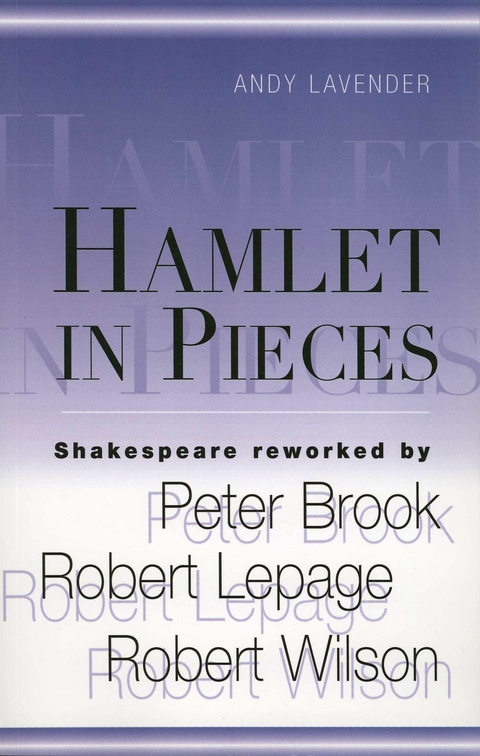

Hamlet In Pieces (eBook)

268 Seiten

Nick Hern Books (Verlag)

978-1-78001-915-4 (ISBN)

Three extraordinary productions of Hamlet by three giants of modern theatre. Peter Brook, Robert Lepage and Robert Wilson have all attempted radical reworkings of Hamlet. This book examines their very different approaches. Brook's Qui Est La - his 'variation' on Hamlet - was first seen in Paris in 1995, incorporating the writings of Artaud, Brecht, Craig, Meyerhold, Stanislavsky and Zeami Motikoyo into edited scenes from Shakespeare's play. He has since tackled the full play in a spare and definitive production which provides the subject of the epilogue to this volume. Lepage's Elsinore is a technically complex tour de force - a multimedia drama on a moving set, with Lepage playing all the characters. Wilson's Hamlet: a monologue, directed, designed and performed by Wilson himself, is a one-man show - but one that needs twenty backstage staff to bring it to life. Vividly reconstructing each of the three productions, the author offers a dyamic combination of casebook and critique, complete with 16 pages of production photos.

2

Qui Est Là • Peter Brook

‘For all his apparent concern with metaphysics, there is no more practical man of the theatre than Brook.’

Richard Eyre1

Last words

On the face of it, Peter Brook spent the last couple of decades of the twentieth century fashioning an oeuvre of millennial masterpieces which have all the resonance of a closing speech at the end of Act 5. There were productions of canonical final works by celebrated playwrights. In 1988 Brook revived (in English rather than French) his 1981 production of The Cherry Orchard, Chekhov’s last play. Two years later he presented Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest, in French, at the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in Paris. On a more expansive tack, there was his version of The Mahabharata (1985), a Sanskrit poem 15 times longer than the Bible and, according to Brook, ‘more universal than Shakespeare’s complete works’.2 Two productions in the 1990s charted abnormal operations of the human brain – L’Homme Qui (1993, presented in English in 1994 as The Man Who), a study of neurological dysfunction which took Oliver Sacks’s book The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat as its starting-point, and Je suis un phénomène (I’m a phenomenon, 1998), which laid out the unusual mental constitution of the Russian mnemonist Solomon Shereshevsky. What better way to top this collection than with a full production, in 2000, of Shakespeare’s Hamlet?

World mythology, the workings of the brain, complex social interactions – Brook’s work is marked by the grandeur of its embrace. It takes big themes and complicated events and attempts to circumscribe their most inner, most outlying, most primal, most final entities. To use a grammatical analogy, Brook’s theatre deals in superlatives, a predilection borne out by the liberal use of superlatives in the director’s descriptions of his own work. Brook talks a lot about ‘truth’, ‘essence’ and the ‘essential’. His fondness for extravagant quintessence found its moment at the turn of the millennium.

Presented in 1995, Qui Est Là belongs to this quest for magnificent overview. The production combined edited scenes from Shakespeare’s Hamlet with the writings of Artaud, Brecht, Craig, Meyerhold, Stanislavsky and Zeami Motikoyo (a Noh theatre master in medieval Japan) – a veritable A to Z of practitioner-thinkers.3 From the outset this was a superbly summative project. Brook was dealing with the Ur-text of modern drama; with the codifications of the director-theorists who most evidently shaped western theatre in the twentieth century; and with an Eastern perspective which provides a decisively alternative reference point. Qui Est Là was posted as the twentieth century’s final word on Shakespeare, on modernist drama, on world theatre.

It is not surprising to find that the central text is Shakespeare’s. Brook has turned to his preferred playwright at pivotal moments throughout his career. In a speech made in 1991 he observed that ‘Shakespeare is always the model that no one has surpassed, his work is always relevant and always contemporary.’4 In his monograph Evoking Shakespeare, Brook celebrates his subject as a playwright who was ‘genetically speaking . . . a phenomenon . . . [with] an amazing, computer-like capacity for registering and processing a tremendously rich variety of impressions’; and as a poet, who has ‘the capacity to see connections where, normally, connections are not obvious.’5

For Brook, Shakespeare uncovers such connections without privileging any single point of view. The poet-playwright amasses scenes of remarkable locational and emotional fluidity, which offer an intensely real image of social interaction and individual experience. His writing leans towards a metaphysical understanding ‘related to an order that had nothing to do with political order’.6 This is Brook’s Shakespeare: capacious of mind, even-handed, a master synthesiser, an expert in the flowing dynamics of theatre, and always inclined to offer meaning beyond the merely literal (and indeed political). Unsurprisingly, the subject of this sketch sounds not unlike Brook himself. It is a disputable account, but Brook’s impatience with the idea of leaving Shakespeare to fend for himself is appealing. Crucially, ‘What we look at [when staging Shakespeare] must seem natural now, today. . . . In other words, the problem is adapting this material to the present moment.’7 This, surely, is a truism of theatre-making too little understood and applied. Brook, meanwhile, rarely lets Shakespeare escape the present moment.

It appears that Brook’s first engagement with Hamlet was at the age of seven, when he performed as the solo actor in a four-hour version (‘by P. Brook and W. Shakespeare’) for his parents, in which he played every part himself.8 His first production for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon was Love’s Labour’s Lost in 1946, marking the beginning of a long relationship with the organisation that would, in 1961, become the Royal Shakespeare Company, and which Brook left when it could no longer accommodate his unorthodox talent. His 1962 RSC production of King Lear, with Paul Scofield in the title role, marked the passage of both European existentialism and Brechtian minimalism into British Shakespearean production. In 1968, as political uprisings spread across Europe and America, Brook returned from Paris to London to present a one-hour ‘work in progress’ at the Round House, part-experiment in performance exercises, part-exploration of The Tempest.9

Nobody needs reminding of Brook’s 1970 production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one of the most celebrated Shakespearean productions ever. It is more easily forgotten that at the time this was a surprising choice of text, given Brook’s inclination towards the more intellectual and problematic plays. The production’s radical anti-sentimentality, its metatheatricality and its bracingly clean style, which owed much to the white-box set designed by Sally Jacobs, a key figure in Brook’s work during this period, consolidated trends which reverberated for at least the next twenty years. When Brook opened the Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord in Paris in 1974, where he has been based ever since, it was with a production of Timon of Athens. He returned to Stratford-upon-Avon and the RSC in 1978 to direct Antony and Cleopatra as an intimate political study. This remains, to date, his last made-in-England production. His 1990 production of The Tempest, with Sotigui Kouyaté as Prospero, marked the integration of the ‘intercultural’ experiments of the 1970s and ’80s into Brook’s Shakespearean work.

In spite of the global travels and the search for transcultural theatre forms, you can chart Brook’s career through his engagement with England’s most iconic playwright. Realist, existentialist, anarchist, early-postmodernist, interculturalist – Brook’s Shakespeare is nothing if not a creature of fashion. ‘Shakespeare is our contemporary,’ observed Brook’s friend Jan Kott. He meant that Shakespeare’s work was peculiarly in tune with dark and violent strains of the 1950s and ’60s. What’s striking about Brook’s Shakespeare is that he is always impeccably up to date, sometimes even anticipatory of shifts in cultural production.

Brook’s Shakespearean work has been underpinned by more consistent concerns. The programme note to the Round House Tempest of 1968 is reminiscent of the statements Brook was to make about Qui Est Là, nearly thirty years later:

The present project is intended to bring fragments of evidence and experience to bear on these questions. The questions are: What is a theatre? What is a play? What is an actor? What is a spectator? What is the relation between them all? What conditions serve this relationship best?10

Throughout his career Brook has had a sharp eye on the mechanics of his medium. Perhaps more than any other director currently alive, he has structured his career as a discipleship in theatrical craft.

Brook’s personal history connects him directly with some influential forebears. He was friends with Edward Gordon Craig. He saw productions directed by Stanislavsky, which were still in the repertory of the Moscow Art Theatre when Brook first visited Moscow. His Russian cousin had been Meyerhold’s assistant, and described for his English relative the extraordinary work he had witnessed. Brook first met Brecht in Berlin in 1950, when his Shakespeare Memorial Theatre production of Measure for Measure was on tour. His encounter with Artaud’s writings in 1959 led him to write avidly on the Frenchman’s ideas for the theatre journal Encore and to produce, with Charles Marowitz, the influential Theatre of Cruelty season of 1964. In 1968 France’s pre-eminent homme du théâtre, Jean-Louis Barrault, gave the actors appearing in Brook’s Round House production of The Tempest a class in breathing, based on exercises...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 3.8.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Anglistik / Amerikanistik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Sprach- / Literaturwissenschaft ► Literaturwissenschaft | |

| Schlagworte | books • Classic • Claudius • Criticism • Drama • Dramaturg • Dramaturgy • elsinore • empty space • Ex Machina • Gertrude • Hamlet • Interpretation • Laertes • Peter Brook • PLAYS • Production • qui est la • Research • robert le page • Robert Wilson • Shakespeare • Theatre |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78001-915-7 / 1780019157 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78001-915-4 / 9781780019154 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich