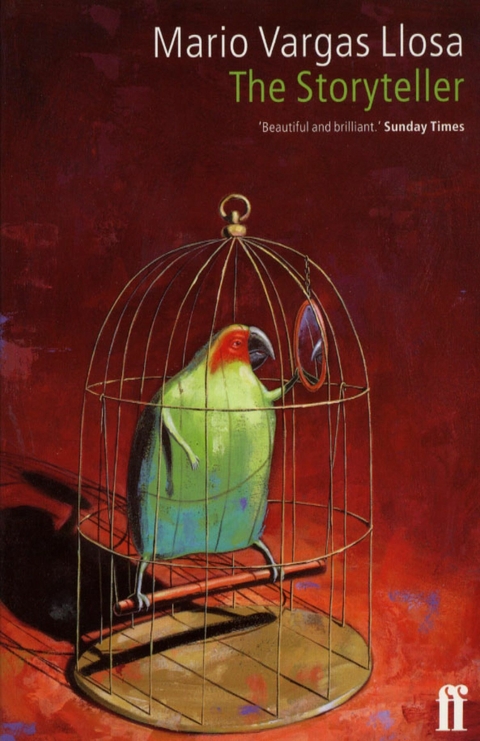

Storyteller (eBook)

200 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-26822-1 (ISBN)

Mario Vargas Llosa was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010. He also won the Cervantes Prize, the most distinguished literary honour in the Spanish-speaking world. His many works include The Feast of the Goat, The Bad Girl and Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter as well as several collections of essays, journalism and plays. He died in April 2025.

WINNER OF THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATUREAt a small gallery in Florence, a Peruvian writer comes across a photograph of a tribal storyteller deep in the Amazon jungle. As he stares at the photograph, it dawns on him that he knows this man. The storyteller is not an Indian at all but his university classmate, Saul Zuratas, who was thought to have disappeared in Israel. As recollections of Zuratas flow through his mind, the writer begins to imagine Zuratas' transformation into a member of the Machiguenga tribe. In The Storyteller, Mario Vargas Llosa has created a spellbinding tale of one man's journey from the modern world to our origins.

With novels including The War of the End of the World, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter, The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto and The Feast of the Goat, Mario Vargas Llosa has established an international reputation as one of the Latin America's most important authors.

SAÚL ZURATAS had a dark birthmark, the color of wine dregs, that covered the entire right side of his face, and unruly red hair as stiff as the bristles of a scrub brush. The birthmark spared neither his ears nor his lips nor his nose, also puffy and misshapen from swollen veins. He was the ugliest lad in the world; but he was also a likable and exceptionally good person. I have never met anyone who, from the very outset, seemed as open, as uncomplicated, as altruistic, and as well-intentioned as Saúl; anyone who showed such simplicity and heart, no matter what the circumstances. I met him when we took our university entrance examinations, and we were quite good friends—insofar as it is possible to be friends with an archangel—especially during the first two years that we were classmates in the Faculty of Letters. The day I met him he informed me, doubled over with laughter and pointing to his birthmark: “They call me Mascarita—Mask Face. Bet you can’t guess why, pal.”

That was the nickname we always knew him by at San Marcos.

He came from Talara and was on familiar terms with everybody. Slang words and popular catch phrases appeared in every sentence he uttered, making it seem as though he were clowning even in his most personal conversations. His problem, he said, was that his father had made too much money with his general store back home; so much that one fine day he’d decided to move to Lima. And since they’d come to the capital his father had taken up Judaism. He wasn’t very religious back in the Piura port town as far as Saúl could remember. He’d occasionally seen him reading the Bible, that, yes, but he’d never bothered to drill it into Mascarita that he belonged to a race and a religion that were different from those of the other boys of the town. But here in Lima, what a change! A real drag! Ridiculous! Chicken pox in old age, that’s what it was! Or rather, the religion of Abraham and Moses. Pucha! We Catholics were the lucky ones. The Catholic religion was a breeze, a measly half-hour Mass every Sunday and Communion every first Friday of the month that was over in no time. But he, on the other hand, had to sit out his Saturdays in the synagogue, hours and hours, swallowing his yawns and pretending to be interested in the rabbi’s sermon—not understanding one word—so as not to disappoint his father, who after all was a very old and very good man. If Mascarita had told him that he’d long since given up believing in God, and that, to put it in a nutshell, he couldn’t care less about belonging to the Chosen People, he’d have given poor Don Salomón a heart attack.

I met Don Salomón one Sunday shortly after meeting Saúl. Saúl had invited me to lunch. They lived in Breña, behind the Colegio La Salle, in a depressing side street off the Avenida Arica. The house was long and narrow, full of old furniture, and there was a talking parrot with a Kafkaesque name and surname who endlessly repeated Saúl’s nickname: “Mascarita! Mascarita!” Father and son lived alone with a maid who had come from Talara with them and not only did the cooking but helped Don Salomón out in the grocery store he’d opened in Lima. “The one that’s got a six-pointed star on the metal grill, pal. It’s called La Estrella, for the Star of David. Can you beat that?”

I was impressed by the affection and kindness with which Mascarita treated his father, a stooped, unshaven old man who suffered from bunions and dragged about in big clumsy shoes that looked like Roman buskins. He spoke Spanish with a strong Russian or Polish accent, even though, as he told me, he had been in Peru for more than twenty years. He had a sharp-witted, likable way about him: “When I was a child I wanted to be a trapeze artist in a circus, but life made a grocer of me in the end. Imagine my disappointment.” Was Saúl his only child? Yes, he was.

And Mascarita’s mother? She had died two years after the family moved to Lima. How sad; judging from this photo, your mother must have been very young, Saúl. Yes, she was. On the one hand, of course, Mascarita had grieved over her death. But, on the other, maybe it was better for her, having a different life. His poor old lady had been very unhappy in Lima. He made signs at me to come closer and lowered his voice (an unnecessary precaution, as we had left Don Salomón fast asleep in a rocking chair in the dining room and were talking in Saúl’s room) to tell me:

“My mother was a Creole from Talara; the old man took up with her soon after coming to this country as a refugee. Apparently, they just lived together until I was born. They got married only then. Can you imagine what it is for a Jew to marry a Christian, what we call a goy? No, you can’t.”

Back in Talara it hadn’t mattered because the only two Jewish families there more or less blended in with the local population. But, on settling in Lima, Saúl’s mother faced numerous problems. She missed home—everything from the nice warm weather and the cloudless sky and bright sun all year round to her family and friends. Moreover, the Jewish community of Lima never accepted her, even though to please Don Salomón she had gone through the ritual of the lustral bath and received instruction from the rabbi in order to fulfill all the rites necessary for conversion. In fact—and Saúl winked a shrewd eye at me—the community didn’t accept her not so much because she was a goy as because she was a little Creole from Talara, a simple woman with no education, who could barely read. Because the Jews of Lima had all turned into a bunch of bourgeois, pal.

He told me all this without a vestige of rancor or dramatization, with a quiet acceptance of something that, apparently, could not have been otherwise. “My old lady and I were as close as fingernail and flesh. She, too, was as bored as an oyster in the synagogue, and without Don Salomón’s catching on, we used to play Yan-Ken-Po on the sly to make those religious Sabbaths go by more quickly. At a distance: she would sit in the front row of the gallery, and I’d be downstairs, with the men. We’d move our hands at the same time and sometimes we’d fall into fits of laughter that horrified the holier-than-thous.” She’d been carried off by galloping cancer, in just a few weeks. And since her death Don Salomón’s world had come tumbling down on top of him.

“That little old man you saw there, taking his nap, was hale and hearty, full of energy and love of life a couple of years ago. The old lady’s death left him a wreck.”

Saúl had entered San Marcos University as a law student to please Don Salomón. As far as Saúl was concerned, he would rather have started giving his father a hand at La Estrella, which was often a headache to Don Salomón and took more out of him than was right at his age. But his father was categorical. Saúl would not set foot behind that counter. Saúl would never wait on a customer. Saúl would not be a shopkeeper like him.

“But why, papa? Are you afraid this face of mine will scare the customers away?” He recounted this to me amid peals of laughter. “The truth is that now that he’s saved up a few shekels, Don Salomón wants the family to make its mark in the world. He can already see a Zuratas—me—in the diplomatic corps or the Chamber of Deputies. Can you imagine!”

Making the family name illustrious through the exercise of a liberal profession was something that didn’t attract Saúl much either. What interested him in life? He himself didn’t know yet, doubtless. He was finding out gradually during the months and years of our friendship, the fifties, in the Peru that, as Mascarita, myself, and our generation were reaching adulthood, was moving from the spurious peace of General Odría’s dictatorship to the uncertainties and novelties of the return to democratic rule in 1956, when Saúl and I were third-year students at San Marcos.

By then he had discovered, without the slightest doubt, what it was that interested him in life. Not in a sudden flash, or with the same conviction as later; nonetheless, the extraordinary machinery had already been set in motion and little by little was pushing him one day here, another there, outlining the maze he eventually would enter, never to leave it again. In 1956 he was studying ethnology as well as law and had made several trips into the jungle. Did he already feel that spellbound fascination for the peoples of the jungle and for unsullied nature, for minute primitive cultures scattered throughout the wooded slopes of the ceja de montaña and the plains of the Amazon below? Was that ardent fellow feeling, sprung from the darkest depths of his personality, already burning within him for those compatriots of ours who from time immemorial had lived there, harassed and grievously harmed, between the wide, slow rivers, dressed in loincloths and marked with tattoos, worshipping the spirits of trees, snakes, clouds, and lightning? Yes, all that had already begun. And I became aware of it just after the incident in the billiard parlor two or three years after our first meeting.

Every so often, between classes, we used to go over to a run-down billiard parlor, which was also a bar, on the Jirón Azángaro, to have ourselves a game. Walking through the streets with Saúl showed how painful a life he must have led at the hands of insolent, nasty people. They would turn around or block his path as he passed, to get a better look at him, staring wide-eyed and making no effort to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 15.11.2012 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Helen Lane |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Schlagworte | Chinua Achebe • Gabriel Garcia Marquez • If on a Winter's Night • JM Coetzee • Roberto Bolano • Salman Rushdie |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-26822-6 / 0571268226 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-26822-1 / 9780571268221 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich