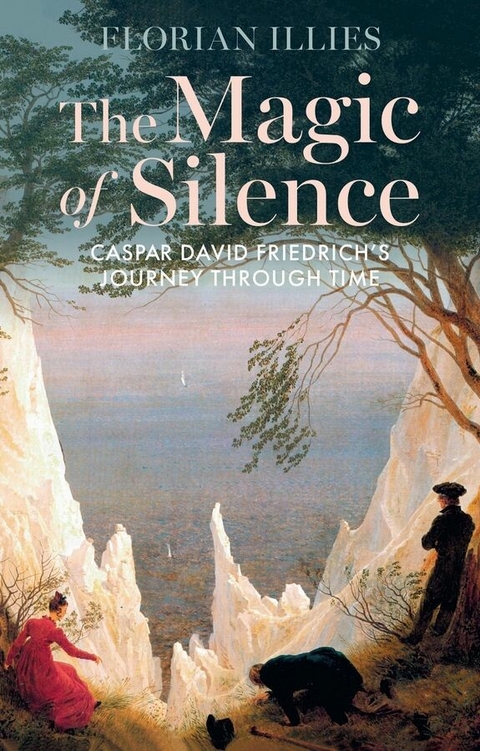

The Magic of Silence (eBook)

183 Seiten

Polity (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6755-3 (ISBN)

In a sweeping journey through time, bestselling author Florian Illies tells the story of Friedrich's paintings and their impact on subsequent generations. Many of his most beautiful paintings were burned, first in his birthplace and then in World War II; others, like the Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, emerge from the mists of history a hundred years after Friedrich's death. Illies recounts the story of how Friedrich's paintings ended up at the Russian czar's court, others among a pile of winter tires in a Mafia car repair shop, and others still in the kitchen of a German social housing apartment. Adored by Hitler and Rainer Maria Rilke, despised by Stalin and by the generation of 68, this compelling narrative dances through 250 years of history as seen through Friedrich's art and life. As a result, the man himself becomes flesh and blood before our very eyes.

Florian Illies is a writer, editor and art historian.

No German painter evokes such strong emotions as Caspar David Friedrich: his evening skies remain icons of longing, his mountain vistas testaments to the grandeur of nature. He inspired Samuel Beckett to write Waiting for Godot and Walt Disney to create Bambi. Goethe, however, was so enraged by the enigmatic melancholy of Friedrich s paintings that he wanted to smash them on the edge of a table.In a sweeping journey through time, bestselling author Florian Illies tells the story of Friedrich s paintings and their impact on subsequent generations. Many of his most beautiful paintings were burned, first in his birthplace and then in World War II; others, like the Chalk Cliffs on R gen, emerge from the mists of history a hundred years after Friedrich's death. Illies recounts the story of how Friedrich's paintings ended up at the Russian czar's court, others among a pile of winter tires in a Mafia car repair shop, and others still in the kitchen of a German social housing apartment. Adored by Hitler and Rainer Maria Rilke, despised by Stalin and by the generation of 68, this compelling narrative dances through 250 years of history as seen through Friedrich s art and life. As a result, the man himself becomes flesh and blood before our very eyes.

PART I

FIRE

On a balmy night in early summer, as the nightingales were singing their last songs in the lilac bushes, a delicate yellow tinge began to lighten the dark blue of the sky. Munich suddenly began to glow: glaring red flames leapt skywards from the colossal Glaspalast in the Botanical Gardens. The radiance of the fire lit up the façades of the nearby Sophienstrasse and Elisenstrasse, and the heavens seemed to flicker like a fireplace. The silence was torn apart by the cracking iron lattice and the shattering windowpanes as they crashed down into the inferno.

In the early morning hours of 6 June 1931, everything that Caspar David Friedrich had loved was perishing in the flames of the Munich Glaspalast: his painting of the rocky Baltic Sea Strand, the object of his undying homesickness; The Port of Greifswald, the wistful picture of his birthplace; the Augustus Bridge in Dresden, which he had seen every day out of his own windows; and, most painfully of all, Evening, the picture of his wife Caroline and their daughter Emma, looking pensively out of the window at a balmy night in early summer. The ravenous flames devoured the dry wood of the stretchers, leaving scraps of canvas to swirl up into the sleepy sky as little black swatches of ash, blown upwards again and again by hot swells of flame until they were lost to sight.

*

Because glass and steel are not flammable – obviously – the management company of the Munich ‘glass palace’ had decided in 1931 to economize, rather than renew the fire insurance that had been negotiated for the building on its construction in 1854.

*

Shortly after 3.30 in the morning on 6 June 1931, the telephone shrilled in Eugen Roth’s flat, just a hundred paces away from the Glaspalast. The editor of the Munich Neueste Nachrichten was on the line, ordering his local reporter to the scene of the burning Glaspalast immediately. Roth pulled his clothes on and, his fingers still befuddled with sleep, threaded a roll of film in his camera, with a glance at the two drawings by Caspar David Friedrich still slumbering on the wall above his bed. The light was dim, but he knew every blade of grass in those pictures: Roth was a passionate collector; he sacrificed every mark he earned by his pen to the city’s art dealers, and the god he worshipped was named Caspar David Friedrich. Before falling asleep every evening, he looked up briefly at that little sheet of paper with the scene of Saxony’s sandstone mountains, and longer at the silent, enchanted Baltic Sea Strand that Friedrich had drawn on Rügen.

Roth had been to the Glaspalast just the previous week for the gala opening of the exhibition of 110 ‘Works of the German Romantics, from Caspar David Friedrich to Moritz von Schwind’. One hundred and ten of the finest Romantic paintings ever gathered, on loan from the leading museums. And in fact he had been planning to go again this afternoon, on his Saturday off, to look and enjoy the pictures at his leisure. Now he was hurrying there twelve hours earlier than planned, already anticipating horror instead of enjoyment. The bells in the Church of the Trinity struck four as he picked his way, coming from Arcisstrasse, across the swollen hoses of the firefighters, thrusting his press card at the police officers. The sky above him was now dark red, and then he saw it: the Glaspalast, or what was left of it. Over its full length and breadth, a monumental 234 by 67 metres, the building was engulfed in flames, the heat pulsing against his face like glowing fists. Taking shelter in a doorway across the road, he took his pencil and notebook from his pocket – but he could not take his eyes off the horrible spectacle. In the early morning hours of this beautiful, terrible June day, Roth recalled each one of the nine paintings by Caspar David Friedrich now smouldering before his eyes: Evening, with the artist’s wife and daughter; the Port of Greifswald; the Bohemian mountain landscape. He thought of the poor man in the Autumn Scene, gathering sparse twigs on deserted fields to light himself a fire in the evening: now he and his bundle of wood were both drowned in the flames. And he recalled the picture he had liked best: the Lady at the Seaside, very tenderly waving a handkerchief after a departing ship. He could still see her salute; it had touched him deeply. Now he knew she was saying good-bye forever. The lady’s white handkerchief was now a flake of black ash; she would never again be seen in this world. Eugen Roth began to write to keep from crying: ‘The gaze wanders over the sea of fire. The tongues of flame lash upwards, roaring up like the tide, sinking back and surging up again, spraying sparks, flickering and snapping, cowering before the firefighters’ crushing jets, then rushing out again a thousandfold, tauntingly dancing and waving and whirling.’

Just a few hours later, Roth’s trembling eyewitness report appeared in the morning edition of the Neueste Nachrichten. The newsboys cried it in the narrow streets of Schwabing and in the broad square – shocked into silence that morning – of Marienplatz. Eugen Roth’s text painted a portrait of that fire with the detail of a Caspar David Friedrich: he saw every single flame, every reflection in the firmament, every seething, hissing wind – it was this text that made him the poet that he would remain in later years. Eventually, he had to leave off writing in the rain of ashes, unable to stand the desperate pigeons flapping through the smoky air, flying oblivious into the sea of flames – suddenly Roth understood that they were looking for their nests in the angles of the iron latticework, where their young, just hatched, had been sleeping peacefully under their wings an hour before.

*

And how did Thomas Mann experience the disturbing glow of that Munich night, the devastating fire in the wee hours of that 6 June that happened to be his fifty-sixth birthday? Did he complain to his wife Katia about the fire department making such a needless noise? Or about the disagreeable smell of smoke ‘affecting’ his nose? Did he go to look at the scene of the fire? We do not know. We only know that he gave a lecture at the university in July as a fundraiser for the victims of the disaster. And that he wrote a little later, in his novel Lotte in Weimar, of Adele Schopenhauer gushing over the ‘divine David Caspar Friedrich’. This is all we know because Mann’s diaries of 1931, which might have recorded his reactions to the conflagration of the treasures of Romantic art, were themselves unromantically burnt by their author in 1945 in the backyard of his house in Pacific Palisades, California.

*

Adolf Hitler and his half-sister’s daughter, Geli Raubal, with whom he had shared a flat at Prinzregentenplatz 16 in Munich for two years – the rent financed by the royalties from Mein Kampf – were startled out of their sleep by the sirens of the fire trucks screaming all through the city. The fire trucks rushed to the Botanical Gardens from all parts of Munich as the citizens tore open their windows and looked in the pale light of dawn towards the city centre and the giant plumes of smoke being blown by the wind as far as Schwabing.

Hundreds of sleepy, distraught people were in the streets, torn between fear and curiosity. The first rays of sunlight to lighten the sky were oppressed by the clouds of sooty ash and the red reflections of the fire. When Hitler arrived in the square at Stachus, he saw that the gigantic glass palace, the city’s diadem, thought to be fireproof, had been transformed into one great boiling sea of flames, its thousands of panes of glass shattered and its iron beams looking like a gigantic, blackened spiderweb jutting up irregularly out of the fire. The crowns of the tall linden trees around the Glaspalast rustled frantically in the wind induced by the fire, their pale green leaves seared and curling in the heat. Just a few days before, Hitler had visited the big exhibition of German Romantics, the most sumptuous compilation from the collections of German museums in decades, here in the Glaspalast. But now all 110 of these irreplaceable paintings – by Runge, Friedrich, Schinkel and more – had been taken by the flames, destroyed, stolen from the cultural memory forever. Hitler felt an irrepressible anger. He promised himself that here, in the city where this disastrous fire took place, he would build a temple to German art, a Haus der Kunst, that would stand forever. And so it happened. And three months after the appalling fire at the Glaspalast, on 18 September 1931, Hitler’s niece Geli Raubal, aged 23 years, would fire a lethal bullet through her lung in the flat they shared, whatever their relationship may have been, at Prinzregentenplatz 16.

*

Caspar David Friedrich was playing with fire. He was constantly drawing human figures even though he was no good at it at all. They had ridiculed him for it at the Academy in Copenhagen, and now in Dresden they were making fun of him again. Life drawing: he just couldn’t get the hang of it. His nudes’ legs were always too long and their torsos flabby. ‘You’re the greatest life-draughtsman here’, the painter Johann Joachim Faber jeered as they sat side by side in the Dresden Academy. ‘I mean, the longest...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 11.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Tony Crawford |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Schlagworte | Air • Allegory • ART • Caspar David Friedrich • Caspar David Friedrich: The Soul of Nature • Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Two Men Contemplating the Moon • Disney • Drama • earth • Emotion • European History • fire • Florian Illies • German History • German Romanticism • Gothic • High Art • Hitler • how did the Nazis engage with art and culture • international reputation of Caspar David Friedrich • Landscape • legacy of Caspar David Friedrich • Leni Riefenstahl • MET exhibition 2025 • Moonrise by the Sea • Nature • Nazi time • painting • Popular Art • Rainer Maria Rilke • reception of Caspar David Friedrich • The Metropolitan Museum of Art • The Monk by the Sea • Tragedy • was Caspar David Friedrich a good painter • Water • what does Disney have to do with Caspar David Friedrich • what does the Mafia have to do with Caspar David Friedrich • what times did Caspar David Friedrich live in • why should we care about Caspar David Friedrich |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6755-0 / 1509567550 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6755-3 / 9781509567553 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich