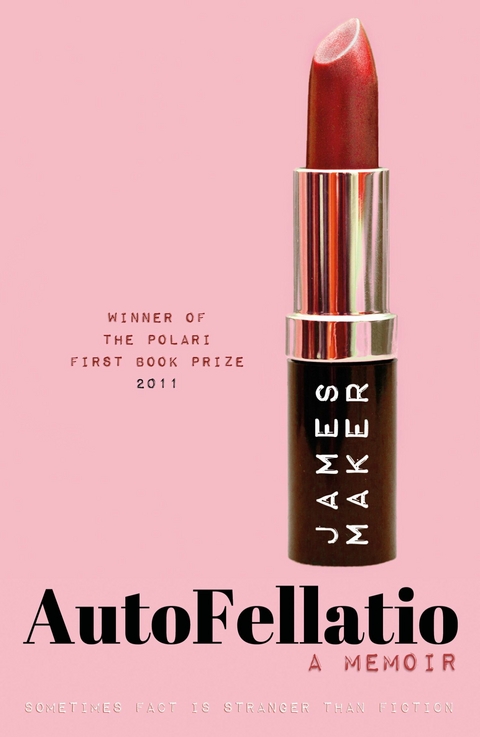

James Maker first trod the b oards i n 1982 as dancer a nd backing vocalist with The Smiths, and was erroneously known as 'The Fifth Smith'. He subsequently became lyricist and lead singer with the 1980s Indie group, Raymonde, and 1990s 'gay' Hard Rock group RPLA. In 2004, he supported the New York Dolls.

Apart from herpes and Lulu - everything is eventually swept awayJust one shimmering pearl of wisdom from pop-star and polymath James Maker, whose worldly observations will (like herpes) once again be on everyone's lips thanks to his award-winning memoir, remastered with new chapters. If you hadn't heard of rock bands Raymonde or RPLA fronted by James in the 80s and 90s you might be forgiven for mistaking AutoFellatio for fiction. But here fact is more fantastical than any novel, as we follow our hero from Bermondsey enfant-terrible to Valencian grande dame, a scenic journey that stops off variously at Morrissey confidant, dominatrix, singer, songwriter and occasional actor, and is literally littered with memorable bons mots and hilarious anecdotes that make you feel like you've hit the wedding-reception jackpot of being unexpectedly seated next to the groom's flamboyant uncle. According to Wikipedia, very few men can perform the act of autofellatio. We never discover whether James is one of them but certainly, as a storyteller, he is one in a million. 'Glitteringly epigrammatic, it's a glam-rock Naked Civil Servant in court shoes. But funnier. And tougher.' MARK SIMPSON'Pistol sharp, loaded with witty one-liners and peppered with Maker's scatter gun observations on life, music and the meaning of good hair.' PAUL BURSTON

An inquisitive adolescent left alone in the house meddles with the telephone. The internet, of course, did not exist then and some of us were driven purely to alert the world to the actuality of our existence. It was either that or BBC1’s Grandstand. An exotic steam percolated into the room as the self-appointed, Sultana of Sodom spoke.

‘Yes?’

‘My name is James Maker...’

The artfully arranged pompadour positioned between a half-eaten cold collation and an undusted aspidistra interjected.

‘Yes?’

‘Well, you see, the thing is...’

‘Yes?’

The voice was high Edwardian and summoned up the image of Kaa, the Indian python of Kipling’s Jungle Book: uncoiling and solicitous, mesmerising you with a mantra before crushing you in its sibilance.

Courtesy of the Infernal Switchboard this was the first important telephone call I was ever to make. I was, in fact, calling the mothership. Feeling isolated and overlooked, I sought the counsel of Quentin Crisp, who was still living in a studio in London’s Chelsea with a published telephone number.

I had, in fact, confused the real Quentin Crisp with John Hurt’s portrayal of him in The Naked Civil Servant which had been broadcast on television the evening before. The latter was a vermilion, lyrical creature addicted to large statements, striding gaily through Bloomsbury while tossing a slipper into the face of ration book convention. The original version was a study in inertia.

Anti-Hero or Expert Loafer: anyone whose singularity of purpose experiments with a new eye shadow while the night sky rains Luftwaffe bombs is always worthy of attention. Advanced self-absorption requires an effort not only of sustained negligence but also a steel-like composure.

‘I’m being ignored.’

I could hear the talons rapidly fanning through the revolving blades of a rolodex of aphorisms and bon mots in search of a suitable card.

Tick-tick-tick-tick-tick-tick-tick.

Pause.

Tick-tick-tick.

‘Faint.’

‘Faint?’

‘FAINT.’

‘Thanks, Quentin.’

I followed this advice with diligence, “fainting” whenever it took my fancy; in the queue of the school’s canteen, on buses and once in the local public library, until it led to concern for my heart. Not unnaturally, my parents thought I might be epileptic, and on the afternoon of a looming hospital appointment I dug my fingers into the door jamb and confessed:

‘I can explain everything.’

Which were also Mussolini’s last words.

Two local girls, council estate Lolitas already inescapably doomed, were both involved in seemingly related incidents that amounted to a rash of teenage suicides.

Kneeling on a kitchen work surface and craning my head out of the window, I saw a crowd collect around the star casualties. As Helen Shapiro’s ‘Keep Away from Other Girls’ perkily wafted over the radio they wheeled out Lesley Laycock’s toenails, lifelessly poking from beneath a sheet of Irish linen. Swiftly, those toenails glided from view and into the back of an ambulance bound for the borough morgue.

Someone formed the cross, a woman in a headscarf cried with Sicilian relish and Jean, my mother’s best friend—and the biggest beehive in Bermondsey—finished off a fish paste bap, folded her arms and announced:

‘That Alice Cooper’s at the bottom of all this.’

My only thought was: I’ve just been upstaged.

Jean was the modern Cassandra of our postcode whose predictions were often uncannily accurate. She had correctly foretold both the Ugandan uprising of 1974 and the coming of the boiler suit as a utilitarian fashion statement. Sadly, she did not foresee her husband’s infidelity with his shorthand secretary and their eventual relocation to a flat above an off licence. Visionaries often see everything, apart from what’s happening on their own bingo cards.

She was once overcome by a prophetic vision in the ladies’ toilets of the Gaumont bingo hall. She temporarily lost consciousness while in the middle of a motion. She was rescued by the assistant manager, who was obliged to climb into the locked cubicle with her. Unceremoniously, she was dragged by the arms through a packed lobby to a waiting taxi.

‘Oh, look at the state of her, shit all up the back of her tights.’

It was the first and last time that a Scotch egg ever passed her lips on an empty digestive system.

Progressive rock and suicide were all the rage in the mid-1970s. I think one gives rise directly to the other. The entire district broke out in a virus of bumper sticker optimism and slogan patches pressed to denim. I lived to loathe. When you’re a teenager you define yourself by that which you hate, because your personality has yet to accommodate anything except an attention deficit disorder and bedtime resistance. It’s the natural progress of puberty and adolescence, but my fledgling seclusion evolved into a self-imposed retreat: Exile on Redlaw Way.

I craved the possibility that the Baader-Meinhof organisation might recruit me, giving me the weapon with which I would assassinate Emerson, Lake and Palmer before quickly moving on to Rick Wakeman.

During high school, and in a gesture towards assimilation, I invited a school friend to visit me at home. Unbidden, he proceeded to play a Van der Graaf Generator album. I had never heard, until the techno boom of the 1990s, vinyl so crammed with proficient pointlessness. I realise it is a question of taste but I fail to see what progressive rock is for, apart from making life seem to last much longer than it actually is. Even its name is an oxymoron.

I was trapped in a manufactured universe of sonic dross where binary replaces spontaneity; where synthesizer players are the feudal lords of the musical landscape, tackling epic and overarching themes in a macrame choker and a scoop neck smock.

Compared to a forced listening of progressive rock music, the victims of Torquemada’s exquisite sadism had it somewhat cushier, I feel. Although the Spanish Inquisition, admittedly, was an exercise in taking masochists far beyond their limits.

But Prog Rock was everywhere and it filled me to the nostrils with semi-sophisticated nihilism. I calmly accepted the whole of Side One while staring at the bedroom door handle in an anguished concentration of telekinesis. When he got up off the bed to play Side Two, I floored him with a desperate rugby tackle, scratched the stylus across the record and asked him to leave.

This he did, and the next day he advertised to the class that I was “unhinged”. Unhinged, a curious choice of word for a fourteen-year-old, it made me sound like Flora Robson in Poison Pen.

This was one of my better reviews and it worked because people left me alone. I was never bulled at school, which is remarkable considering what

I used to turn up in. I wasn’t particularly aggrieved at not being popular because, to my mind, almost everybody else was a cunt in any case. Besides,

I was already formulating other plans.

Suicide. In a distorted idea of romanticism, I believed that if you had not attempted suicide at least once, you were probably not going to be a terribly interesting person when you grew up.

Conversely, a pumped stomach of barbiturates identified you as someone whom I’d like to meet. Without entering the dominion of lofty notions, suicide is an unpleasant and serious business but it can also be the ultimate manifestation or protest act; not of frustration and ennui, but of control and even arrogance.

Complex people with a tendency towards self-destruction can be fascinating in a way that someone who is abundant in cheer may never be. In any case, too much cheer in a person is so fatiguing on a practical level alone, because it constantly barrages you with buoyancy.

From an artistic standpoint, we know that inner demons and mortal struggle can produce exceptional creativity. Or to rephrase: no one who ever particularly minded whether they were served peas or beans with their oven chips ever galvanised an art movement, or antagonised the public with a small yet vital detail in their daily dress.

I like arrogance in its pure form, which should not be mistook for obnoxiousness. Obnoxiousness is cheap, unbearable and available to anyone. Arrogance can be exciting and infectious; pour charisma into the mélange and you have pure sex. Arrogance misplaced is unattractive, and tends to produce itself in people who are physically too short for the gesture.

I think that the incandescence of self-belief, or at least its appearance, is a necessary ingredient to a certain success. In my case, its form is the execution of the perfect omelette which, in its way, is just as important as Patricia Highsmith.

The evening following the teenage suicides I picked idly at the body of a dead cod and returned to my bedroom.

My sanctum was an amethyst daubed cell decorated with a map of metropolitan New York, which I was determined to use one day, posters of male rock stars dressed in “female apparel”, and a sepia newspaper clipping of the Houston mass murder, Dean Corll. My parents saw it as the building of a shrine to an evident and burgeoning perversity. Obviously, they knew me.

I was forever rearranging what little furniture there was to achieve the effect of a fully self-contained private apartment. There was a balcony that offered an aspect to the surrounding concrete dream of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Pop / Rock | |

| Schlagworte | Humour • LGBT • London • Memoir • music • Queer • Spain |

| ISBN-10 | 1-912620-14-6 / 1912620146 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-912620-14-2 / 9781912620142 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich