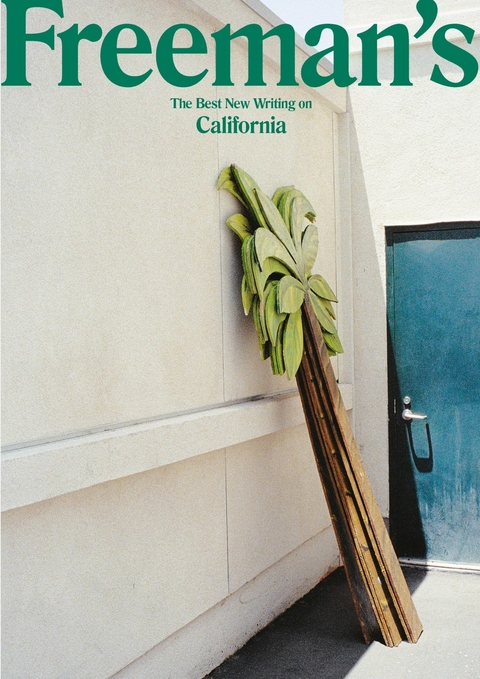

Freeman's California (eBook)

304 Seiten

Grove Press UK (Verlag)

978-1-61185-906-5 (ISBN)

John Freeman was the editor of Granta until 2013. His books include How to Read a Novelist, Tales of Two Cities, Tales of Two Americas and Maps, his debut collection of poems. He is the executive editor at Literary Hub and teaches at the New School and New York University. His work has appeared in the New Yorker and the Paris Review and has been translated into twenty-two languages.

John Freeman was the editor of Granta until 2013. His books include How to Read a Novelist, Tales of Two Cities, Tales of Two Americas and Maps, his debut collection of poems. He is the executive editor at Literary Hub and teaches at the New School and New York University. His work has appeared in the New Yorker and the Paris Review and has been translated into twenty-two languages.

Introduction

JOHN FREEMAN

He didn’t tell us where we were going.

This was not unusual. My father loved pointless drives. He’d hustle us into the car and then we’d tool across town. No destination. Sometimes these drives went on for fifteen minutes.

Sometimes several hours.

We’d meander home from church the long way, stopping at open houses. Are we going to live here? No, let’s just look, he’d reply.

Do I need to say all the homes we ogled were much bigger than ours?

And so I grew up in the multiverse. Have you heard of this term? The theory that reality is simply a series of stacked versions of itself.

This idea—that something else was always simultaneously happening elsewhere—called to my father, and so that Christmas night in 1985 my mother, my brothers, and I—there are three of us—knew we could have been going anywhere.

We passed the malls, then the turnoff to the adjacent suburbs. Then it seemed clear we were going to downtown Sacramento.

Our hearts sank.

My father ran a family service agency in the city that provided health and human services. They did things the government gave up on. Meals on Wheels programs, counseled people getting on or off welfare.

The office was a big old home with sticky floors and it smelled of Tab cola. Most of the time he stashed us in a room with no toys and we were told to wait.

The whole place had the low, quiet ache of disappointment.

And looking back I suppose it should have … that’s what the agency dealt in, how to cope with disappointment.

It was dark now and we had sailed right past his work; none of the streets were looking familiar. My mother was talking quietly to my father as they drove.

Where are we?

We’re here. Come on, help me with this.

My father opened the back of our banana-colored station wagon and yanked out several wrapped presents.

Come on guys.

We followed him and my mother to the door. All of us had paper routes, and though we lacked any kind of social IQ, we were experts in front doors.

This was the kind of metal that would bang if you tried to one-hop the paper to the porch and hit the door by accident.

My dad rapped it loudly. RAP RAP RAP. A light turned on. The metal door opened and a woman appeared. She was dressed for work in the kind of outfit Lucy wore in I Love Lucy. She looked confused but friendly.

Hi we’re your neighbors from United Way, and we just wanted to say Merry Christmas.

By this point, my brothers and I were holding the presents.

We still didn’t know what we were doing there, but the woman behind the door, she had figured out why. Her eyes softened, and then she put on the face you make when you have another face you need to cover up.

Oh you are so kind. Thank you …!

A child our age appeared behind the woman.

This is my daughter …

There we stood on the other side of the door. Two families. Ours, the five of us, and theirs, the two of them.

That’s when the girl our age burst into tears and ran back into the house.

We have been talking a lot in recent years about privilege. White privilege, male privilege, straight privilege. I know I have benefited from all these things, but when I have to identify a period where I understood—before I could articulate—what any of these things meant, I think of that night.

We use a horrible phrase to describe such incidents: teachable moments. But who are they teaching? And what? At age eleven the lesson, for me, was too complex. What was supposed to be an objective demonstration in generosity—giving is good—turned into a tutorial in the invisibility of power. That it takes power to give, and power to create moments for learning, rather than have them thrust upon you. The woman’s daughter had decoded all of it in under a second and it made her feel ashamed.

It took me years to understand that, because as a middle-class striver, I had other teachable lessons I was paying attention to—mostly in books. You read the books, you followed the plan, you took the classes, you did the right activities, you got into the schools that enlarged your life progressively, sequentially, logically, coherently.

But of course, we often learn the most from what we see. It sits inside us like a spinning top, moving of its own accord, until we grab it.

That Christmas set one such dynamo in motion.

Here is another one.

All those nights I stayed up late as a teenager, reading books, doing my homework, determined to get into college, I often shared the dining room table with my mother, who was a social worker in Sacramento, like my father—a professional listener. Most of her patients were in hospice, and this was the 1980s, so they were cancer patients, Alzheimer patients, and early AIDS patients, dying in terror. Lonely and afraid, angry, bewildered. Why has this happened to me? She once told me they said this a lot.

While I dutifully extracted the teachable lessons from the core curricula of the San Joaquin Unified School District, she wrote notes of her visits to patients in Vacaville, Sonora, Placer County.

I see her in memory’s lamp, bent over her notebook transcribing their stories, and I now know there was something holy in what she was doing. While I was racing to turn myself into an excavator for meaning, she had turned herself into an abacus for pain. Recording and measuring and holding what was often seen, but remained invisible—the stories of people who were suffering.

I tell you this now because eventually the meaning of these stories caught up with me—because life did. I did get into the good school, I did move to New York, which is where you went to work in the storytelling business. I did get a job in publishing and did turn myself into a freelance writer. I spent a decade reviewing books full-time, and became an editor of a literary magazine, and did all the things a striver in my field with a passion for literature might try to do because I genuinely loved it—I loved the possibilities of literature. What it was and what it stood for. I believed in all of it.

All these things are true.

But here’s another story from the multiverse. What if I told you that if I had to construct a reunion of this gift exchange, say, fifteen years after the fact, just two members of my family would be standing on that West Sacramento porch? My older brother would be homeless, living out of a van on a construction site in Oregon, sometimes wrestling his 120-pound malamute in the dark so she knew he was top dog; my younger brother would be under full restraint at a psychiatric ward, in the throes of a schizophrenic breakdown. My mother would already be in the steep decline of a frontal lobe dementia. And come to think of it, my father, who took care of her through this illness—the one that garbled her speech, then stumbled her legs, then sat her down, and then turned her into just her ability to smile, before clicking off the lamp behind her eyes—he wouldn’t be there on that reunion porch either. No, he’d be waiting for a social worker to come to his door to listen to him talk about his unbelievable problem.

California has for a long time been seen as the Valhalla of far-flung dreams. The far shore. It’s why my family moved back there in 1984. The place of starting over. The end of the horizon, as Joan Didion famously wrote.

California is also, however, the site of real people’s homes. Real people’s lives. Real lives begun as dreams and perhaps dribbled into boredom. Or unraveled into nightmares. Or fabulously, miraculously achieved. This schism—between what California represents in popular imagination and what it is, what it means to live there, to be from there—means Californians collide constantly with the rupture of existence.

How to dream the life we are already living.

One of the best definitions of literature I ever heard was uttered by a California writer, T. C. Boyle. Literature, he said, is how we dream in story. One of the best definitions of immigration was also told to me by a Californian—Natalie Diaz. Immigration, she said, is dreaming with the body. You imagine a better future somewhere else, because you must, and so you move—you move your body into a dream.

Literature from California is among the most alive in the world, in part because it is being driven by these questions. California has more immigrants than any other state in the U.S.—nearly a quarter of the immigrant population. Nearly a third of the state is foreign-born. In a world in the throes of a massive global migration, this makes California the most literary state of an increasingly unliterate nation.

A state built with, stolen, and powered by immigrants is an army of living untold dreams. So here are some of them, dreams lived, deferred, daydreamed, nightmare-dreamt. This special issue of Freeman’s is an attempt to celebrate these stories, these writers, and to follow the fog lamp of their imagination into the other issues California faces, which, in fact, mirror some of the most important issues of our time—from global climate change, to the radical and pernicious stockpiling of wealth in one minuscule group of individuals.

If our civilization is ever going to reckon with these realities, it is going to have to dream better in story. Californians do not, most of them, have the luxury to postpone such dreams. The state is literally on fire.

Driving down 1-280 in his opening piece, Jaime Cortez stops at a rest stop in the Central Valley and sees what he thinks is a collection of people living out of their cars. Instead he discovers it packed...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.10.2019 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 1 x 8pp colour plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Anthologien |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Fotokunst | |

| Schlagworte | Bay Area • Big Sur • Carmel • Elaine Castillo • geoff dyer • Los Angeles • Rachel Kushner • Sacramento • San Francisco • tommy orange |

| ISBN-10 | 1-61185-906-9 / 1611859069 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-61185-906-5 / 9781611859065 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich