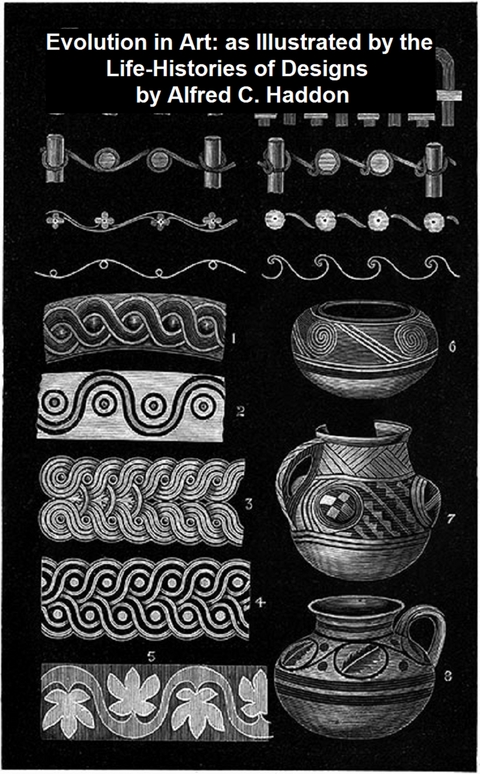

Evolution in Art: as Illustrated by the Life-Histories of Designs (eBook)

211 Seiten

Seltzer Books (Verlag)

978-1-4554-4615-5 (ISBN)

First published in 1895.According to the Preface: 'Notwithstanding the immense number of books, dissertations, and papers which have been written on pictorial and decorative art, I venture to add one more to their number. I profess to be neither an artist nor an art critic, but simply a biologist who has had his attention turned to the subject of decorative art. One of my objects is to show that delineations have an individuality and a life-history which can be studied quite irrespectively of their artistic merit.'

First published in 1895. According to the Preface: "e;Notwithstanding the immense number of books, dissertations, and papers which have been written on pictorial and decorative art, I venture to add one more to their number. I profess to be neither an artist nor an art critic, but simply a biologist who has had his attention turned to the subject of decorative art. One of my objects is to show that delineations have an individuality and a life-history which can be studied quite irrespectively of their artistic merit."e;

Perhaps no manufacture is of such importance to anthropologists as pottery. In Europe pottery first appeared in what is termed by archæologists the Neolithic Age, or that period of human history when man had learnt to neatly chip and to polish his stone implements, but had not as yet discovered metal. Amongst living people the Australians and the Polynesians are the only great groups among whom pottery is unknown.[31] There can be little doubt that the ceramic art has been independently discovered in various parts of the world, and Mr. Cushing believes that this has been the case even in America.

Earthen vessels are comparatively easy to make, and though they are brittle, their fragments, when properly baked, are almost indestructible. The history of man is unconsciously written largely on shards, and the elucidation of these unwritten records is as interesting and important as the deciphering of the cuneiform inscriptions on the clay tablets of Assyria. The Book of Pots has yet to be written, but materials for its compilation lie scattered throughout the great literature of archæology, anthropology, and ceramics, and in the specimens in a multitude of museums and collections. The scientific treatment of the subject has been sketched out mainly by W. H. Holmes and F. H. Cushing, and I have not hesitated to borrow largely from the publications of these American anthropologists.

There are three principal methods of making clay vessels—1, by coiling; 2, by modelling; or 3, by casting.

In the first method longer or shorter rope-like pieces of clay are formed. These are laid down in a spiral, and the vessel is built up by a continuation of the same process.

In modelling, or moulding, a lump of clay is taken, and this is first worked with the hands, and then the clay is gradually beaten into the desired shape and thickness by means of a wooden mallet, which hits against a stone or other object that is held inside the incipient vessel.

The third method, by casting, is very rarely employed except by quite civilised peoples. It was a comparatively late discovery that clay vessels could be cast within hollow moulds if the paste was made thin enough.

The coiling and moulding processes are in some places employed side by side, and a vessel may be commenced in the latter method and finished by coiling. (Fig. 55.) This is done by the Nicobarese,[32] Pueblo Indians, and other peoples.

The subject of the forms and decoration of pottery is so important for our study that it will be advisable to quote at considerable length some of the American investigations which bear upon it. Nowhere than in that continent are conditions more favourable to a scientific study of the evolution of ceramics, and our American colleagues happily are fully alive to this fact. Their researches afford valuable sidelights upon the probable history of European prehistoric ceramics.

Mr. J. D. Hunter,[33] writing of the Mississippi tribes in 1823, says that they spread the clay “over blocks of wood, which have been formed into shapes to suit their convenience or fancy. When sufficiently dried they are removed from the moulds, placed in proper situations, and burned to a hardness suitable to their intended uses. Another method practised by them is to coat the inner surface of baskets, made of rushes or willows, with clay, to any required thickness, and when dry, to burn them as above described.”

Messrs. Squier and Davis,[34] referring to the vessels of the Gulf Indians, say:—“In the construction of those of large size, it was customary to model them in baskets of willow or splints, which at the proper period were burned off, leaving the vessel perfect in form, and retaining the somewhat ornamental markings of their moulds. Some of those found on the Ohio seem to have been modelled in bags or nettings of coarse thread or twisted bark. These practices are still retained by some of the remote western tribes.”

Mr. W. H. Holmes[35] points out that “clay has no inherent qualities of a nature to impose a given form or class of forms upon its products, as have wood, bark, bone, or stone. It is so mobile as to be quite free to take form from surroundings.... In early stages of culture the processes of art are closely akin to those of nature, the human agent hardly ranking as more than a part of the environment. The primitive artist does not proceed by methods identical with our own. He does not deliberately and freely examine all departments of nature or art, and select for models those things most convenient or most agreeable to fancy; neither does he experiment with the view of inventing new forms. What he attempts depends almost absolutely upon what happens to be suggested by preceding forms.

“The range of models in the ceramic art is at first very limited, and includes only those utensils devoted to the particular use to which the clay vessels are to be applied; later, closely associated objects and utensils are copied. In the first stages of art, when a savage makes a weapon, he modifies or copies a weapon; when he makes a vessel he modifies or copies a vessel” (pp. 445, 446).

The discovery of the art of making pottery was probably in all cases adventitious, the clay being first used for some other purpose. “The use of clay as a cement in repairing utensils, in protecting combustible vessels from injury by fire, or in building up the walls of shallow vessels, may also have led to the formation of discs or cups, afterwards independently constructed. In any case the objects or utensils with which the clay was associated in its earliest use would impress their forms upon it. Thus, if clay were used in deepening or mending vessels of stone by a given people, it would, when used independently by that people, tend to assume shapes suggested by stone vessels. The same may be said of its use in connection with wood and wicker, or with vessels of other materials. Forms of vessels so derived may be said to have an adventitious origin, yet they are essentially copies, although not so by design” (p. 445). In other words, such pottery is primitively skeuomorphic. Ceramic biomorphs will be dealt with in a later chapter.

Mr. Holmes further points out that the shapes first assumed by vessels in clay depend upon the shape of the vessels employed at the time of the introduction of the art, and these depend, to a great extent, upon the kind and grade of culture of the people acquiring the art, and upon the resources of the country in which they live.

A few examples will suffice. Mr. Holmes (loc. cit., pp. 383, 448) figures an oblong wooden vessel with a projecting rim, which is narrow at the sides but broad at the ends; it is in fact a sort of winged trough; this is sometimes copied in clay. It is evident that the elongated terminal shelf-like projections are more suited to a wooden than to an earthen vessel.

In Fig. 53 we have an Iroquois bark-vessel. Mr. Cushing[36] informs us that in order to produce this form of utensil from a single piece of bark, it is necessary to cut pieces out of the margin and fold it. Each fold, when stitched together in the shaping of the vessel, forms a corner at the rim. These corners, and the borders which they form, are decorated with short lines and combinations of lines, composed of coarse embroideries with dyed porcupine quills. Clay vessels (Fig. 54), which strikingly resemble the shape and decoration of these birch or linden bark vessels, are of common occurrence in the lake regions of the United States. There can be but little doubt that the clay vessels are directly derived from the bark vessels.

Fig. 53.—Iroquois bark vessel; after Cushing.

Fig. 54.—Rectangular, or Iroquois, type of earthen vessel; after Cushing.

Mr. Cushing’s long and intimate knowledge of the Zuñi Indians has enabled him to speak with authority on matters which might be merely happy suggestions by other anthropologists. Any one can guess at origins and meanings, but there are few who know at first-hand, and who therefore can act as interpreters to the student at home. The following account of Zuñi pottery is taken from Mr. Cushing’s paper, entitled “A Study of Pueblo Pottery as illustrative of Zuñi Culture Growth.”

So far as language indicates, the earliest Zuñi water vessels were tubes of wood or sections of cane. The latter must speedily have given way to the use of gourds. While the gourd was large and convenient in form, it was difficult of transportation, owing to its fragility. To overcome this it was encased in a coarse sort of wicker-work. Of this there is evidence among the Zuñis, in the shape of a series of rudely encased gourd vessels into which the sacred water is said to have been transferred from the tubes.

This crude beginning of the wicker-art in connection with water vessels points towards the development of the wonderful water-tight baskets of the south-west, explaining, too, the resemblance of many of its typical forms to the shapes of gourd vessels. The name for these vessels also supports this view.

Mr. Cushing suggests that water-tight osiery, once known, however difficult of manufacture, would displace the general use of gourd vessels. While the growth of the gourd was restricted to limited areas, the materials for basketry were anywhere at hand. Basket vessels were far...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-4554-4615-7 / 1455446157 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-4554-4615-5 / 9781455446155 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,0 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich