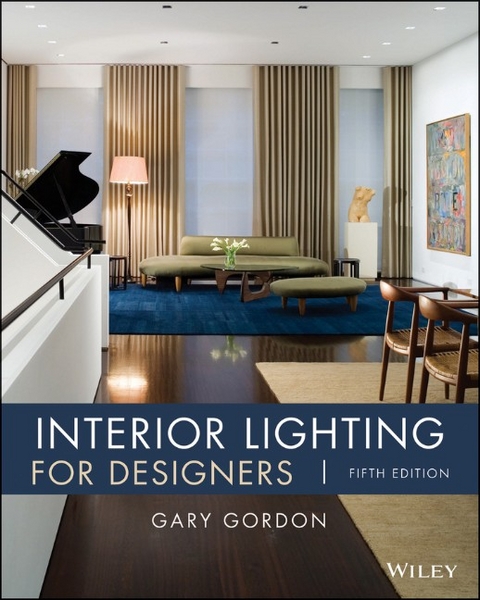

Interior Lighting for Designers (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-41506-1 (ISBN)

Gary Gordon, FIALD, FIES is founder and?Principal Lighting Designer?of Gary Gordon LLC.?He has designed lighting systems for more than 1,000 corporate, hospitality,?institutional, residential, and retail projects. He has taught graduate and undergraduate courses at the Lighting Institute at Parsons School of Design in New York, where he helped develop the Parsons MFA Lighting Design program.

Mr. Gordon is a Fellow of both the Illuminating Engineering Society and the International Association of Lighting Designers.?As three-term president of the National Council on Qualifications for the Lighting Professions (NCQLP), he helped to establish the first national certificationprogram for lighting professionals.

Gary Gordon, FIALD, FIES is founder and?Principal Lighting Designer?of Gary Gordon LLC.?He has designed lighting systems for more than 1,000 corporate, hospitality,?institutional, residential, and retail projects. He has taught graduate and undergraduate courses at the Lighting Institute at Parsons School of Design in New York, where he helped develop the Parsons MFA Lighting Design program. Mr. Gordon is a Fellow of both the Illuminating Engineering Society and the International Association of Lighting Designers.?As three-term president of the National Council on Qualifications for the Lighting Professions (NCQLP), he helped to establish the first national certificationprogram for lighting professionals.

PREFACE xi

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii

INTRODUCTION xv

PART I DESIGN FACTORS 1

1 THE LIGHTING DESIGN PROCESS 3

2 PERCEPTION AND VISION 6

Visible Light 6

The Eye and Brain 6

Brightness Perception 11

Color Perception 12

3 LIGHT AND HEALTH 16

Photobiology and Nonvisual Effects 16

The Aging Eye 19

Light Therapy 20

Assisted-Living and Eldercare Facilities 20

Dynamic Electric Lighting 21

4 PSYCHOLOGY OF LIGHT 22

Emotional Impact 22

Degrees of Stimulation 22

Degrees of Brightness Contrast 23

The Three Elements of Light 27

Subjective Impressions 30

Certainty 33

Variation 33

5 PATTERNS OF BRIGHTNESS 36

Direction and Distribution of Light 36

Surface Finishes and Refl ectances 43

Three-Dimensional Form 45

Glare and Sparkle 49

6 COLOR OF LIGHT 56

Color Temperature 58

Color Rendering 59

Subjective Impressions 60

Surface Finishes and Color of Light 61

7 MEASUREMENT OF LIGHT 65

Quantitative Illumination 65

PART II LIGHT SOURCES 71

8 DAYLIGHT 73

Daylight Design 74

Shading Devices 80

Glazing Materials 83

Quantity of Interior Daylight 83

9 FILAMENT SOURCES 86

Lamp Shapes 86

Lamp Bases 86

Filaments 87

Light Output 89

Tungsten-Halogen Lamps 91

Lamp Types 93

Low-Voltage Lamps 97

U.S. Legislation 99

Colored Light 100

10 LOW-INTENSITY DISCHARGE SOURCES 104

Fluorescent Lamps 104

Lamp Characteristics 113

Health and Safety Concerns 115

11 HIGH-INTENSITY DISCHARGE SOURCES 117

Mercury Vapor Lamps 117

High-Pressure Sodium Lamps 118

Metal Halide Lamps 118

Lamp Characteristics 120

Low-Pressure Sodium Lamps 124

12 SOLID-STATE LIGHTING 125

LEDs 125

Organic Light-Emitting Diodes 133

13 AUXILIARY EQUIPMENT 134

Ballasts 134

Drivers 141

Transformers 142

PART III INTERIOR ILLUMINATION 145

14 LIGHT CONTROL 147

Control of Light Direction 147

Glare Control 158

15 LUMINAIRES 163

Housings 163

Light and Glare Control 167

Decorative Luminaires 199

Emergency and Exit Luminaires 200

16 SUSTAINABLE DESIGN 204

Integrating Light and Architecture 205

Visual Clarity 205

Architectural Surfaces 209

Task Lighting 214

Ambient Lighting 215

Lighting Three-Dimensional Objects 219

Balance of Brightness 224

Successful Solutions 233

17 DESIGN VERIFICATION METHODS 234

Recommended Illuminance Values 234

Surface Refl ectance 236

Illuminance Calculations 237

Postoccupancy Evaluation 247

18 ELECTRICITY AND LIGHTING CONTROLS 249

Principles of Electricity 249

Switch Control 254

Dimming Control 258

Digital Lighting Controls 265

Energy-Management Controls 267

19 DOCUMENTATION 268

Construction Documents 268

EPILOGUE 291

APPENDIX 293

REFERENCES 319

GLOSSARY 321

INDEX 331

2

PERCEPTION AND VISION

Visible Light

What we perceive as light is a narrow band of electromagnetic energy, ranging from approximately 380 to 760 nanometers (nm), technically known as optical radiation. Only wavelengths in this range stimulate receptors in the eye that permit vision (Figure 2.1). These wavelengths are also called visible energy, even though we cannot directly see them.

Figure 2.1 Visible light is a narrow region of the total electromagnetic spectrum, which includes radio waves, infrared, ultraviolet, and X rays. The physical difference is purely the wavelength of the radiation, but the effects are very different. Within the narrow band to which the eye is sensitive, different wavelengths give different colors. See also Color Plate 7.

In a perfect vacuum, light travels at approximately 186,000 miles per second. When light travels through glass or water or another transparent substance, it is slowed down to a velocity that depends on the density of the medium through which it is transmitted (Figure 2.2). This slowing down of light is what causes prisms to bend light and lenses to form images.

Figure 2.2 The law of refraction (Snell’s law) states that when light passes from medium A into medium B, the sine of the angle of incidence (i) bears a constant ratio to the sine of the angle of refraction (r).

When light is bent by a prism, each wavelength is refracted at a different angle so that the emergent beam emanates from the prism as a fan of light, yielding all of the spectral colors (see Color Plate 8).

All electromagnetic radiation is similar. The physical difference between radio waves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, and X rays is their wavelength. A spectral color is light of a specific wavelength; it exhibits deep chromatic saturation. Hue is the attribute of color perception denoted by what we call violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red. (Isaac Newton had chosen these seven colors in the spectrum somewhat arbitrarily by analogy with the seven notes of the musical scale.)

The Eye and Brain

A parallel is often drawn between the human eye and a camera. Yet visual perception involves much more than an optical image projected on the retina of the eye and transferred “photographically” by the brain. Rather than superior optics, visual perception is mostly the result of brain interpretation.

The human eye is primarily a device that gathers information about the outside world. Its focusing lens throws a minute inverted image onto a dense mosaic of light-sensitive receptors, which convert the patterns of light energy into chains of electrical impulses that the brain will interpret (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Cross section of the human eye.

The simplest way to form an image is not with a lens, however, but with a pinhole. In Figure 2.4, a ray from each point of the object reaches only a single point on the screen, the two parts being connected by a straight line passing through the pinhole. Each part of the object illuminates a corresponding part of the screen, so that an upside-down image of the object is formed. The pinhole image is dim, however, because the hole must be small (allowing little light to pass through) if the image is to be sharp.

Figure 2.4 Forming an image with a pinhole.

A lens is able to form a much brighter image. It collects a bundle of light rays from each point of the object and directs them to corresponding points on the screen, thus giving a bright image (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 Forming an image with a lens. The lens shown is a pair of prisms; image-forming lenses have curved surfaces.

The lens of the human eye is built up from its center, with cells being added all through life, although growth gradually slows down. The center is thus the oldest part, and as the cells age they become more compact and they harden. As a result, the lens stiffens and is less able to change its shape to accommodate varying distances (presbyopia) (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 Loss of accommodation of the lens of the eye with aging.

Lenses only work well when they fit properly and are adjusted correctly. Sometimes the lens is not suited to the eye in which it finds itself: (1) the lens focuses the image in front of or behind the retina instead of on it, giving “short” sight (nearsighted or myopic) or “long” sight (farsighted or hyperopic); (2) the lens is not truly spherical, giving distortion and, in some directions, blurring of the image (astigmatic); or (3) the cornea is irregular or pitted.

Fortunately, almost all optical defects can be corrected by adding artificial lenses, which we call eyeglasses. Eyeglasses correct for errors of focus (called accommodation) by changing the power of the lens of the eye; they correct for distortion (called astigmatism) by adding a nonspherical component. Ordinary glasses do not correct damage to the surface of the cornea, but corneal lenses, fitted to the eye itself, serve to give a fresh surface to the cornea.

The iris is the pigmented part of the eye. It is found in a wide range of colors, but the color has no impact on vision as long as it is opaque. The iris is a muscle that forms the pupil. Light passes through the pupil to the lens, which lies immediately behind it. This muscle contracts to reduce the aperture of the lens in bright light as well as when the eyes converge to view near objects.

People with light-colored eyes lack pigment in their macula, the small dot about the size of a pinhead that sits conveniently in the most centralized portion of the eye as light passes through the pupil to reach the retina. The more pigmented the macula, the better it handles the impact of light: light-eyed people are more affected by glare. (Approximately 16 percent of Americans have light-colored eyes; there is also evidence that they are more likely to have cataracts as they age.)

The retina is a thin sheet of interconnected nerve cells, which include the light-sensitive cells that convert light into electrical impulses. The two kinds of light-receptor cells—rods and cones—are named after their appearance as viewed under a microscope (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7 The retina.

Until recently, it was assumed that the cones function in high levels of illumination, providing color vision, and that the rods function under low levels of illumination, yielding only shades of gray. Color vision, using the cones of the retina, is called photopic; the gray world given by the rods in dim light (such as under starlight at night) is called scotopic.

Recent research, however, suggests that both rods and cones are active at high illuminance, with each contributing to different aspects of vision. When both rods and cones are active (such as under street lighting at night), vision is called mesopic.

The eyes supply the brain with information coded into chains of electrical impulses. But the “seeing” of objects is determined only partially by these neural signals. The brain searches for the best interpretation of available data. The perception of an object is a hypothesis, suggested and tested by sensory signals and knowledge derived from previous experience.

Usually the hypothesis is correct, and we perceive a world of separate solid objects in a surrounding space. Sometimes the evaluation is incorrect; we call this an illusion. The ambiguous shapes seen in Figures2.8 and 2.9 illustrate how the same pattern of stimulation at the eye gives rise to different perceptions.

Figure 2.8 Necker cube. When you stare at the dot, the cube flips as the brain entertains two different depth hypotheses.

Figure 2.9 Ambiguous shapes. Is it a vase or two faces in profile?

Brightness Perception

We speak of light entering the eye, called luminance, which gives rise to the sensation of brightness. Illuminance, which is the density of light received on a surface, is measured by various kinds of photometers, including the familiar photographer’s exposure meter.

Brightness is a subjective experience. We hear someone say, “What a bright day!” and we know what is meant by that. But this sensation of brightness can only be partly attributed to the intensity of light entering the eyes.

Brightness is a result of: (1) the intensity of light falling on a given region of the retina at a certain time, (2) the intensity of light to which the retina has been subjected in the recent past (called adaptation), and (3) the intensities of light falling on other regions of the retina (called contrast).

Figure 2.10 demonstrates how the intensity of surrounding areas affects the perception of brightness. A given region looks brighter if its surroundings are dark, and a given color looks more intense if it is surrounded by its complementary color.

Figure 2.10 Simultaneous contrast.

If the eyes are kept in low light for some time, they grow more sensitive, and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.1.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Design / Innenarchitektur / Mode |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Schlagworte | Architecture • Architektur • Innenarchitektur • Interior design • LED lighting design, LED, energy efficient lighting, sustainable lighting design, lighting interior design, lighting floor plan, creative lighting design, technical lighting design, lighting design text, lighting design book, learn lighting design |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-41506-X / 111841506X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-41506-1 / 9781118415061 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich