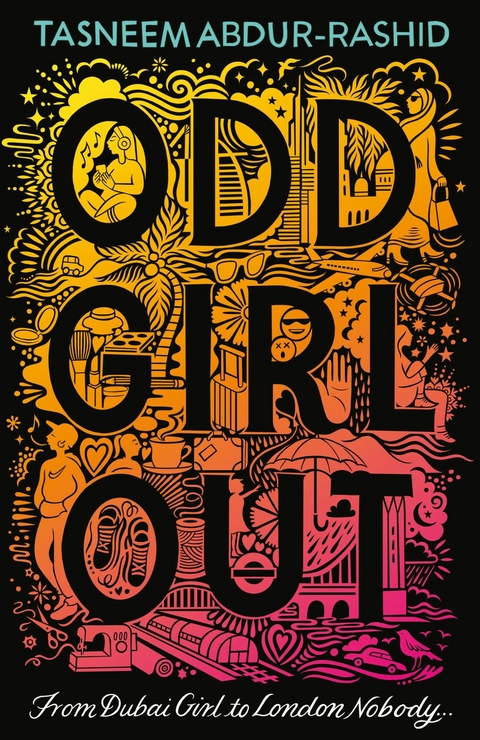

Odd Girl Out (eBook)

368 Seiten

David Fickling Books (Verlag)

978-1-78845-343-1 (ISBN)

Tasneem Abdur-Rashid is a British Bengali writer born and raised in London. A mother of two, Tasneem has worked across media, PR and communications both in the UK and in the UAE. Tasneem's adult rom-com Finding Mr Perfectly Fine was published by Zaffre/Bonnier in 2022, and her second adult novel The Thirty Before Thirty List publishes in 2024. She co-hosts the award-winning podcast Not Another Mum Pod and is also a phenomenal home cook.Odd Girl Out is her YA debut.

Tasneem Abdur-Rashid is a British Bengali writer born and raised in London. A mother of two, Tasneem has worked across media, PR and communications both in the UK and in the UAE. Tasneem's adult rom-com Finding Mr Perfectly Fine was published by Zaffre/Bonnier in 2022, and her second adult novel The Thirty Before Thirty List publishes in 2024. She co-hosts the award-winning podcast Not Another Mum Pod and is also a phenomenal home cook.Odd Girl Out is her YA debut.

The plane makes its descent towards London Heathrow, splatters of rain decorating the windowpane. Everything is green, brown and grey, a world apart from the yellow desert I’ve left behind. I sneak a glance at my mum next to me. Her eyes are closed, but judging by the vein bulging on her forehead, she feels just as anxious as I do. I resist the urge to slip my hand into hers, like I used to do until I was far too old to be clutching onto my mum like she was my comfort blanket.

It feels weird to be coming here in September instead of June. The sky is greyer than it was the last time I was here, echoing my feelings. I’ve visited the UK with my mum every summer since I was born, escaping the blistering Dubai heat to spend three glorious months with my extended family in London. My dad could never get enough leave from work, so he’d join us for the last couple of weeks, and we’d go to theme parks, West End shows, football matches. I used to moan so much when he’d drag me to the Emirates stadium. As much as he tried to instil a love of football in me, I wasn’t interested in a bunch of sweaty men kicking a ball around a field.

Now, I’d do anything to go to a match with him. My heart constricts, as it always does when I think of my dad and my brand-new, broken life.

‘Mum, we’re here,’ I whisper loudly after we’ve made a bumpy landing and the plane has ground to a halt. People have started getting up and are shrugging on their jackets, but her eyes remain firmly shut.

‘Mum!’ I implore, more urgently, as I have a vision of us being the last people on the plane, and the cabin crew having to carry Mum out on a stretcher. Her eyes open slowly, like it’s a struggle to keep her eyelids apart, like it’s a struggle to exist. My body slackens in relief.

‘Sorry, jaan,’ she says, her voice strained from too many hours of crying. ‘Come on, let’s go.’

London Heathrow is drab and dreary compared to the glitz and glam of Dubai International Airport, even more so than usual. Usually, I’m excited to be here. Usually, I’ve already switched to my UK eSIM, and as we queue at passport control, I start posting on Snapchat and text all my friends. Usually, I’ve got a big list of things I want to do while I’m here, starting with shopping on Oxford Street and analysing all the latest fashion trends.

Now, the unknown stretches out before me. I see the cracks I had previously glossed over: the worn carpets, the smelly toilets, the passport control people eyeing us suspiciously as they scan our British passports.

‘Boro Affa! Maaryah! Over here!’ Uncle Kamil, one of Mum’s four brothers, calls out to us as we walk through arrivals with our trolleys. My face breaks into my first smile in ages and I hurry over to him and bury myself in his arms. My mum’s the eldest of seven, with four younger brothers and two younger sisters. Most of them live in North London with their families. ‘Boro Affa’ means ‘eldest sister’ in Sylheti, the dialect spoken in the region of Bangladesh we’re from.

‘All right, Kam?’ Mum says, giving him a quick hug. He grabs my trolley containing whatever material pieces of my life I had been able to salvage within the luggage allowance – my favourite cold-weather-friendly clothes, a couple of books, framed photos – and Mum falls into step with him. I trail behind them, trying not to eavesdrop on their conversation. My uncle speaks so loudly that it’s hard not to. I hear him say ‘bastard’ and ‘that piece of shit’, and I guess he’s referring to my dad. My stomach churns and I try to swallow the lump that has permanently lodged itself into my throat.

‘Maary-jaan! Come here my darling!’ Nani cries as she throws open the front door of their Victorian terrace, grabbing me and pulling me right into her bosom. I hug my grandmother back, and before I can stop myself, I burst into tears. That sets her off, and the two of us stand in the doorway crying until she gently pulls away and reaches for my mum. Then Mum starts sniffling, and Nani whispers stuff in her ear. I take that as my cue to leave.

Hearing the commotion, my uncles and aunts gather in the hallway, followed by all my little cousins who are running, sliding and jumping down the stairs, before launching themselves at me, the only granddaughter on this side of the family. I trip over a scooter that’s been discarded in the hallway amongst the countless shoes, coats and brown Amazon boxes.

‘How are you coping? Are you OK?’ Aunty Ayesha asks me when I’ve been greeted by everyone and finally managed to go up to her room to change out of my usual travelling outfit of joggers and a hoodie and into my PJs.

Aunty Ayesha and Uncle Ish are the only unmarried ones and still live at home with my grandparents. Uncle Kamil lives here too, with his wife, Aunty Yasmin, and two little sons; Ilyas the tornado and baby Zayd. Also in the house today are Uncle Ridwaan who lives in Palmers Green with his wife, Aunty Basheerah, and their three kids, who are the least sociable of my cousins. I can hear them crying somewhere in the house. Then we’ve got my other aunt, who I call Khalamoni, her husband, Uncle Abdulla, and their two boys, Kareem and Yousef. The only ones who aren’t here today are Uncle Kaif, his pregnant wife, Aunty Amira, and their son Eesa, because they live in Singapore.

There’s always a LOT going on in big, fat Bengali family on my mum’s side, and I used to love the noise, the mess, the pandemonium. I used to love how every summer I managed to slot right in like a missing jigsaw piece. I used to find the confusion comforting. But now, the chaos is overwhelming, and all I want to do is curl up into a ball and hide away in my old bedroom, in my old house, in my old life.

‘Sort of,’ I reply, as once again, my eyes begin to prickle with tears. Crying, like hugging, is something I never did much of, pre-divorce. I guess I was lucky I didn’t have much to cry about back then. Now, anything seems to set me off, and it’s proper embarrassing.

‘I’m so sorry this has happened,’ Aunty Ayesha says, drawing me in for another cuddle.

‘Tell me about it,’ I reply, grateful for the opportunity to talk about it with her. ‘I keep thinking that they’ll patch things up. I mean, they’ve been together for seventeen years! How can they fall out of love like that? None of it makes sense to me. There must be other reasons, right? People with kids don’t just break up like that because they’ve “grown apart”.’

Aunty Ayesha looks away. ‘I don’t know,’ she says quietly. ‘Crappy things happen sometimes, even if it doesn’t make sense.’

‘For real.’

We fall silent as we both sit there on her bed, like we’ve done many times before. With only six years between us, we’ve always been more friends than aunt and niece. Today feels different, though. I don’t feel like watching Korean dramas with her or making funny Tiktoks. I want her to tell me that everything’s going to be OK, but she doesn’t. As she stares out of the bedroom window, I realize she looks as lost as I feel.

Dinner is part sombre, part raucous. The adults are trying not to say anything to upset Mum and me, and the kids are running riot. Ilyas climbs onto the kitchen island and jumps off onto the tiled floor yelling, ‘I can fly!’ There’s so much noise that it’s difficult to have a conversation, and I’m thankful for it. Talking to Aunty Ayesha is one thing, but I’m not ready to listen to how much the rest of the Choudhury clan hate my dad’s guts.

All around me, everyone is tucking into their food like they haven’t eaten for days. I’m not surprised; Nani’s food is banging and this is a family of foodies. The funny thing is, Mum and I are probably the only ones who actually haven’t eaten properly in ages, but we’re the ones who are pushing food around our plates.

I know I should eat. My mum is a crap cook, so who knows when I’ll have a decent meal next. In Dubai, we had house help who did all that, and Mum never had to bother. But it’s hard to enjoy food when your whole existence has been cut into two. And post-divorce isn’t just about your parents having broken up; it’s moving across the world and starting up a whole new life in a new country, new school, new friends, new house. It’s saying goodbye to everything and everyone you once knew and feeling petrified that you won’t be able to fit in to your new life. It’s not knowing when you’ll see your dad next, but feeling too afraid to mention him for fear of upsetting your mum and her whole extended family.

‘Is that all you’re having? Here, take some lamb,’ Nani scolds, grabbing my plate and adding a ladleful of tender lamb curry onto a bed of buttery pilau rice....

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.4.2025 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kinder- / Jugendbuch ► Jugendbücher ab 12 Jahre |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78845-343-3 / 1788453433 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78845-343-1 / 9781788453431 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich