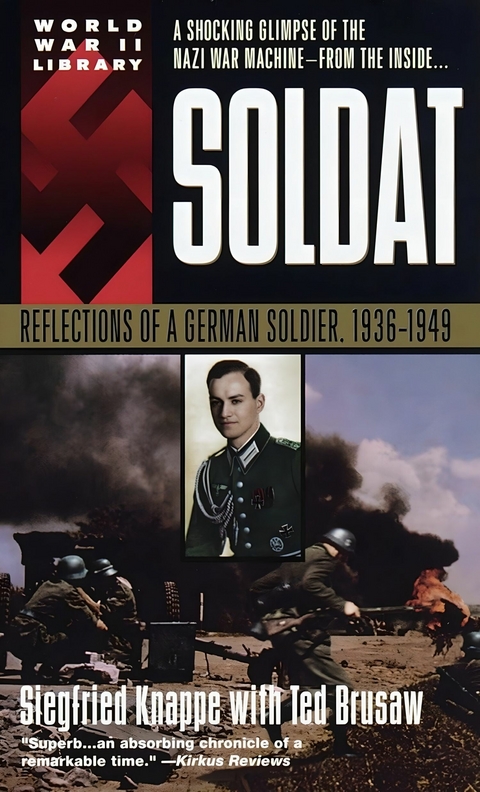

Soldat (eBook)

267 Seiten

Publishdrive (Verlag)

978-0-00-103304-7 (ISBN)

Paris. The Somme. The Italian Campaign. The Russian Front. And inside Hitler's bunker during The Battle of Berlin . . . World War II through the eyes of a solider of the Reich.

Siegfried Knappe fought, was wounded, and survived battles in nearly every major Wehrmacht campaign. His astonishing career begins with Hitler's rise to power-and ends with a five-year term in a Russian prison camp, after the Allies rolled victoriously into the smoking rubble of Berlin. The enormous range of Knappe's fighting experiences provides an unrivaled combat history of World War II, and a great deal more besides.

Based on Knappe's wartime diaries, filled with 16 pages of photos he smuggled into the West at war's end, Soldat delivers a rare opportunity for the reader to understand how a ruthless psychopath motivated an entire generation of ordinary Germans to carry out his monstrous schemes . . . and offers stunning insight into the life of a soldier in Hitler's army.

'Remarkable! World War II from inside the Wehrmacht.'-Kirkus Reviews

PART TWO: Sunny Times 1936-1939

The road was getting steeper and more curving, with the view around each bend becoming more spectacular than the last. The five of us in the car Werner Friedrich, Hans Liebelt, Siegfried Ebert, Ernst Michaelis, and I had graduated from gymnasium together just a week before, on March 6, 1936. We had all entered gymnasium together nine years ago, at the age of ten, and two years ago we began planning this ski trip to celebrate our graduation.

Friedrich was exuberant, as usual, challenging everyone to a race once we reached the ski area and assuring us all that we did not stand a chance. We were all anticipating the trip with great excitement.

Finally, we rounded the last steep, sharp curve, and there, slightly below us, nestled securely in the lap of the Sudeten Mountains of Silesia, was our ski village. We found a place to leave our car, a sedan that ‘belonged to Liebelt’s father, and followed signs to the cabin check-in office in a running snowball fight, Our faces must have looked quite flushed, from both the cold air and the running, to the old man we startled when we charged through the door.

“Hello there,” he said. “What can I do for you?” He peered at us over oval wire-framed glasses.

“We have a reservation for one of your cabins,” Ebert said. “The name is Siegfried Ebert.”

“Let’s see” He flipped through what looked like scrap papers. “Here it is!” he said. “I am Hoffer.” He extended his hand, and in turn we each shook it. His grip was firm in spite of his advanced age and his frail build. We each put our share of the money on the counter. He slowly counted the money and carefully placed it in an old wooden lock box, then sorted through a pile of keys until he found the one he wanted.

“Here you are,” he said. He smiled, his old eyes twinkling behind his glasses as he dangled the key before Ebert. “Have a good time, boys.”

Ebert took the key, and we herded each other out of the office, eager to begin our adventure. We began to unload our gear from the car, which amounted to throwing everything into a pile.

“Here, carry this,” came an order, followed by some thing thudding into my back.

I knew it was Friedrich without turning around. As usual, he was taking charge and dividing up the gear to be carried to the cabin. When we were all finally loaded to Friedrich’s satisfaction, we trudged up the mountain, toward our cabin. Although the temperature was only 28 degrees Fahrenheit, the steep climb up the mountain made us sweat.

The cabin was one big rectangular room with two windows, one facing east, or front, and the other facing the slopes to the west. On the north wall was a huge fireplace, complete with a spit for roasting meat, a bar for hanging kettles, and a small iron grid for skillets, pots, pans, and other utensils hanging from the mantel. On the south wall were two sets of bunks. We had been instructed to bring sleeping bags and pillows.

“Let’s ski!” yelled Friedrich.

In a rush, we got our skis out of the pile of gear. We had to go only a few paces until we were at a slope. Down we would go, then back up we would struggle, only to be unable to resist going down one more time.

We one more timed until we could barely crawl. Finally, we’d had enough and made our way back to the cabin. We decided to eat in the village, because we were too tired to cook.

The aroma inside the café immediately provoked hunger rumblings in our very empty bellies. There were no customers, and there appeared to be no employees either. We were all fidgety from hunger. Friedrich and I leaned our chairs back on two legs.

“Take it easy on the furniture!” a familiar voice boomed as Herr Hoffer popped into the room as if from nowhere. Our chairs dropped to all fours promptly. “Hello, boys. Can’t stand your own cooking, huh? No matter, Frau Hoffer will feed you.” A second later she came bustling into the room and told us what we would be eating.

Knowing that our supper was on the way, we settled down. I looked through the window. From our table we could barely see the foot of the mountain, which was muted by the soft glow of the few street-lights. A gentle lazy snowfall had begun, with large aimless flakes wafting slowly to earth. In the warm café, with the aroma of food being prepared, we enjoyed a satisfied sense of being free and yet cared for. Outside, a farm-boy about our age led a draft horse that was pulling a sled loaded high with hay slowly along the road. Old Herr Hoffer and another man about his age had begun a game of chess at a table near us, carrying on a constant conversation about politics as they played.

Frau Hoffer emerged from the kitchen pushing a cart laden with food. She deftly placed the bowls of food in front of us and handed us each an empty plate and the necessary silverware. Without further conversation, we ate every morsel she had placed in front of us. We all seemed to lean back and heave a satisfied sigh at nearly the same time. Frau Hoffer must have been watching us from the kitchen, because here she came again, with the empty cart. She quickly cleared the table and left,us to ourselves for our own after dinner discussion. Suddenly we were aware of Herr Hoffer’s voice becoming louder.

“Hitler is going to get us into another war!” he said emphatically.

“Why do you say that?” his chess partner demanded.

“Because Hitler is a gambler, and gamblers will not quit until they lose.”

“I do not know how you can say that,” his chess partner responded. “He has provided people with jobs, he has restored the economy, he has stopped all the political brawling in the streets, he has built the autobahns, he has torn up the Versailles Treaty and restored national pride, he has even reclaimed the Rhineland.” The old man finally ran out of breath.

“And how has he done all those things?” Herr Hoffer demanded. “He has provided jobs by building up the armaments industry. What do you think he is planning to do with all that fire-power?

Admire it? And he restored peace to the streets by putting all his political opponents and a lot of Jews as well into concentration camps.”

We all glanced furtively at Michaelis, who was Jewish.

“So why do you say that Hitler is a gambler?” the other old man asked.

“What do you think would have happened if the French had resisted when our troops marched into the Rhineland?” Herr Hoffer asked. “Our pitiful force would have been wiped out. But Hitler was playing poker, and he gambled that his opponent would not call his bluff. He won that hand, and he may win more but eventually he is going to overstep himself, because gamblers never quit when they are winning. They always keep betting until they lose.”

“But he is just getting back what the Versailles Treaty took away from us,” his friend protested.

Herr Hoffer rose and walked to the fireplace, where he knocked the ashes out of his pipe. “He won’t stop there,” he said. “He will continue until he gets us into another war. And at what cost?” He turned and waved his hand in our direction. “At the cost of these boys’ lives, most likely, as well as the lives of millions of others.”

“What an old grouch!” Friedrich whispered to the rest of us.

“I am not so sure he is not right,” Michaelis offered in a quiet voice.

No one responded. Michaelis’s being Jewish made us all uneasy in the context of the old men’s conversation.

We returned to our cabin, where we got a new fire going quickly, because it was cold.

Up at daybreak the next morning, we made tea, had breakfast, and were hiking up the mountain with our skis on our shoulders in less than an hour. As we crested the mountain, the view into Czechoslovakia was as breathtaking as the view on the German side. We skied all day, speeding down the glittering pristine slope and then trudging back up with our skis on our shoulders. Then we skied the cross-country route we had laid out the evening before.

In late afternoon, we finally decided to call it a day and skied down the German side of the mountain to our cabin. After getting a fire going, we poured some beans into a kettle, covered them with water, and hung them over the fire. Then we peeled potatoes and did the same with them. Soon both were boiling busily and we waited patiently for them to cook. Half an hour later the potatoes were soft to the touch of a fork and obviously ready, but the beans appeared to be as hard as ever. We set the potatoes to the side of the fire to keep them warm as the beans continued to cook. An hour later the beans were still boiling briskly, but no more done than ever.

“What kind of beans did you buy, Knappe?” Friedrich demanded.

“Just beans. Why? Are there different kinds?” I asked sheepishly.

“I don’t know, but are you sure these were meant to be cooked?

They have been on that ‘fire an hour and a half!”

“Let’s eat the potatoes,” Ebert suggested. “We will eat the beans whenever they are ready.”

We divided the potatoes into five equal portions and devoured them with bread and butter and a fresh pot of tea. We felt better after eating, although the potatoes alone did not completely satisfy our appetites.

Together, we slowly cleaned up the mess, checked the fire, and put fresh water over the still boiling beans.

“Want some American popcorn?” Liebeit asked rising to go get it from his gear.

“What is that?” I asked.

“I will show you,” Liebeit said, returning with a bag of tiny kernels of corn and a skillet. “My uncle in America sent this to us from...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.8.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| ISBN-10 | 0-00-103304-2 / 0001033042 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-00-103304-7 / 9780001033047 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,6 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich