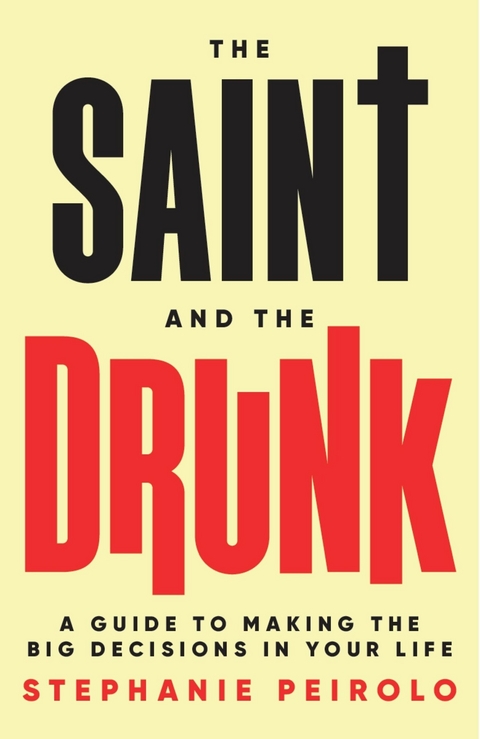

Saint and The Drunk (eBook)

434 Seiten

Shepheard Walwyn Publishers (Verlag)

978-1-916517-12-7 (ISBN)

What if you had an internal compass that could provide direction at every turning point in your life?

The Saint and the Drunk - A Guide to Making the Big Decisions in Your Life shows people how to build a practice of intentional decision making.

Everyone has access to an understanding of what we are called to do or be in the world . But for many that access has been obscured by cultural or familial narratives, trauma or grief. This is a practical book that considers the very real responsibilities most people have. The exercises and writing prompts help to reach that deep knowing within people so that they can build a life that is congruent with their values while moving closer to their dreams.

The author shares her deeply moving, and at times, tragic personal journey that successfully affirms that the discernment process outlined in this book can help anyone, no matter their circumstance, to make even the most difficult decisions in their lives.

The Saint and the Drunk - A Guide to Making the Big Decisions In Your Life shows how to use ancient spiritual tools with a modern, spiritual-but-not-religious approach to make major life decisions with intention and clarity.

What if you had an internal compass that could provide direction at every turning point in your life? The Saint and the Drunk - A Guide to Making the Big Decisions in Your Life shows people how to build a practice of intentional decision making. Everyone has access to an understanding of what we are called to do or be in the world . But for many that access has been obscured by cultural or familial narratives, trauma or grief. This is a practical book that considers the very real responsibilities most people have. The exercises and writing prompts help to reach that deep knowing within people so that they can build a life that is congruent with their values while moving closer to their dreams. The author shares her deeply moving, and at times, tragic personal journey that successfully affirms that the discernment process outlined in this book can help anyone, no matter their circumstance, to make even the most difficult decisions in their lives. The Saint and the Drunk - A Guide to Making the Big Decisions In Your Life shows how to use ancient spiritual tools with a modern, spiritual-but-not-religious approach to make major life decisions with intention and clarity.

CHAPTER TWO

The Saint

Who was Ignatius of Loyola?

Ignatius was born in 1491 and became a mercenary. He was not, in his early life, a particularly holy guy. In the first lines of his autobiography, he described himself in this way: “Up to his twenty-sixth year the heart of Ignatius was enthralled by the vanities of the world. His special delight was in the military life, and he seemed led by a strong and empty desire of gaining for himself a great name.”1 In May of 1521 he was struck by a cannonball which broke one leg and wounded the other. Since he wanted to continue to be a soldier to engage in “his special delight” he opted for additional surgeries and a longer time recuperating so he could regain full function in both legs. He recuperated at his family’s home, which was a small castle in northern Spain, and had few books to read, all religious texts.

He started to consider a life devoted to God. He was trying to decide what to do once he was healed. Priest or soldier? Holy man or mercenary? He noticed that when he thought about devoting his life to God, he felt good. When he daydreamed about returning to the battlefield, or “what he should do in honor of an illustrious lady, how he should journey to the city where she was, in what words he would address her, and what bright and pleasant sayings he would make use of, what manner of warlike exploits he should perform to please her.”2 he felt good about that as well. Thinking about serving God made him feel good in a specific way. It was sustaining and sustained. It lasted in a steady flow. “When he thought of worldly things it gave him great pleasure, but afterward he found himself dry and sad.”3

This was to become the foundation for the Spiritual Exercises. Ignatius thought of the Exercises as similar to physical exercise. “For just as taking a walk, journeying on foot, and running are bodily exercises, so we call Spiritual Exercises every way of preparing and disposing the soul to rid itself of all inordinate attachments, and after their removal, seeking and finding the will of God in the disposition of our life …” (SE #1) He gave very specific directions for how to do these exercises, the way a trainer might outline a set of physical exercises to increase flexibility. The result is a process for listening and observing the internal movements of one’s imagination, mind and spirit developed by a soldier with a broken leg who was stuck in a drafty castle.

The concept of “inordinate attachments” is central to Ignatian thought. The Buddhist tradition also attends to the spiritual challenges of attachment. Clinging to people, situations, narratives or material goods causes suffering. Ignatius also explored the need to get rid of all our inordinate attachments in order to be able to clearly see what we are to do.

Ignatius decided to devote himself to God, and leave behind his life as a mercenary. But Ignatius went about it with a misguided fervor for a solitary spiritual life. For almost a year, he spent much of his time in prayer in a cave, living as a beggar and eating little.

“Ignatius, after coming close to suicide because of his ferocious spiritual regimen, consulted a spiritual director, who brought him back down to earth and helped him to rejoin the human race.” (Harbaugh p. xiv) Ignatius decided to return to school and study, which he did for another twelve years, an older soldier studying with young men. But the young men were intrigued with his Spiritual Exercises, the instructions he had written to help others replicate the process he himself had undergone. He founded the Jesuits, or the Order of the Society of Jesus. They exist today, in fact, the current Catholic Pope, Francis, is a Jesuit.

The Spiritual Exercises are predicated on the idea that any one of us can go directly to the Divine and get guidance. Yes, the Jesuit order is part of the Catholic Church. Ignatius was very much a Catholic. But what’s radical and useful to me in the context of this book is the idea that there is a direct channel between each of us and the Divine that will allow us to get guidance. We don’t need an interlocutor or go-between, a priest or any other spiritual leader. In his “Introductory Observations” Ignatius speaks directly to the person who is taking someone through the Exercises and says that the director shouldn’t get in the way of God’s direct communication with the person going through the Exercises “to permit the Creator to deal directly with the creature and the creature directly with his Creator and Lord.” (SE #15). Stop and consider that this was written by a Catholic priest in the 16th century, telling a spiritual director, who would have often been a priest, not to get in the way of God directly communicating with the person doing the Exercises.

The Spiritual Exercises are divided into four sections, called “weeks,” and focus on meditations on biblical stories of episodes in the life of Jesus, inviting us to consider aspects of how those stories guide us to a new or changed understanding of our call or vocation in the world.

In this book, I am not following the format of the weeks, nor will I be referring to the biblical texts. There are many excellent resources for people who are interested in using the Spiritual Exercises as a religious retreat. I am taking some of the fundamentals of the Spiritual Exercises and Ignatian Spirituality and using them as a foundation upon which anyone can build a practice of discernment.

Discernment is a way of making decisions that is intentional and spiritual. Ignatius then, and the Jesuits now, believe that the Spiritual Exercises can help you understand what God wants you to do in the world. I find the process of discernment useful for anyone looking for a values based, intentional process for making decisions. Here are a few other Jesuit concepts that are foundational to the Exercises, Jesuit spirituality and this book.

Imaginative Contemplation

One of the key techniques that Ignatius uses is embodied imaginative contemplation. He calls it Application of the Senses. He suggests that we imagine that we are in a biblical scene. In quiet contemplation, we are to imagine every aspect of what being in our body in such a scene would be like. Is it dusty? Is it hot? Am I thirsty? What does the chair feel like where Jesus just sat? Who would I be in the scene? I then sit quietly and imagine what my body is experiencing through my senses. Then I get curious about what is coming up for me emotionally. Do I feel angry? Sad? I’m just observing, uncritically, and if there is nothing arising for me, I just sit quietly in that imagined space.

In that long ago conversation I had with Danielle in the white conference room with the grand piano, this was the technique I explained to her. She was trying to discern if she should leave her career in advertising and become a photographer. I suggested that she quiet her mind and imagine her day as a photographer. What would it feel like to wake up if that was her job? How did she feel about going to work in the morning? What was it like to go through the day? I invited her to go into as much detail as she wanted, to really paint a picture for herself, to envision the scenes in detail. Then see how she felt in her body. Check in with her emotional ecosystem as she went through this exercise. Go all the way through to the end of the day, returning home in her imagination and looking back on her imagined day. How did she feel? I suggested she then do the same exercise for continuing to stay in her existing job.

I have been surprised at what comes up for me when I am in this state of embodied imaginative contemplation. Sometimes the feedback I get from myself is garbled, like listening to a foreign language I’m studying when it’s spoken by a native speaker. At first, I can only catch a word here and there. Then I get better and can sometimes understand sentences. Now imagine that the native speaker you are trying to communicate with is someone you love who loves you but who can’t speak your language. Imagine how intently you would be listening, how you would take in not just the words which you don’t know yet, but the intonation, the body movements, the hand gestures. You’d learn pretty quickly in that attitude. It can be the same with learning discernment.

The Divine is in all things, including us

Everything is sacred, including you and me. Our work, our family life, our bodies, our minds. Holy, holy, holy. The term “vocation” is usually used to talk about vowed religious, nuns, priests, pastors. I’ve widened the aperture for vocation to include our work in the world. And I use work expansively – parenting is work, grandparenting is work, caregiving is work, relationships with others are work, being part of community is work, art is work. If we believe that our work is sacred, that we are ministering to one another in all our interactions, would we take decisions we make about work or how we connect to others more seriously? Would we be more intentional?

It’s a change of heart

The intellectual is always useful, but in Ignatian spirituality intellect is not more important than heart and spirit. Our society tends to privilege the intellect. Great passions of the heart, the sense that we must do a thing or follow a certain path, are important, even if they can’t be justified or validated by intellect or the culture in which we live. Ignatius had big feelings, and he tried things that sometimes failed4.

Ignatius wasn’t teaching theology. He was sharing how he reoriented himself. He changed his heart and in doing that changed his orientation to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.5.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie ► Sucht / Drogen | |

| Schlagworte | addiction • alcoholism • drug addition |

| ISBN-10 | 1-916517-12-9 / 1916517129 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-916517-12-7 / 9781916517127 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich