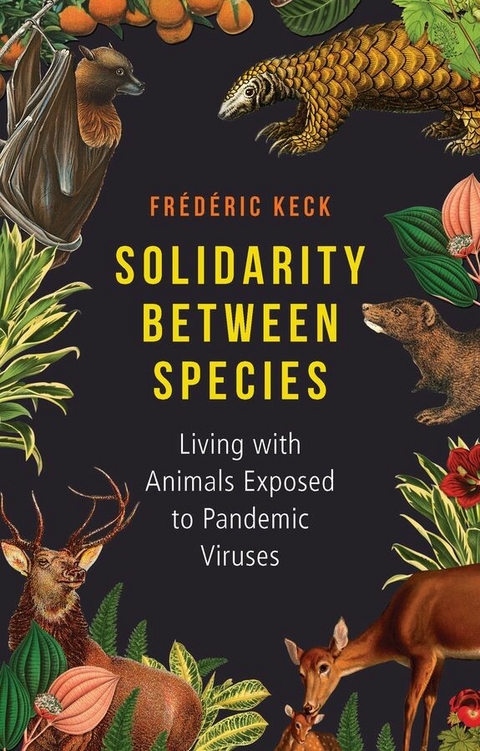

Solidarity Between Species (eBook)

This book examines how the Covid-19 pandemic can be described as a biopolitical crisis, taking into account a fact often overlooked by commentators: Covid-19 is a zoonosis, a disease transmissible between animal species. The Sars-Cov2 virus causing this respiratory disease circulated in bats before passing to humans under as-yet mysterious conditions, and it was transmitted from humans to other species, notably mink and deer.

Building on Michel Foucault's revival of the term 'biopolitics' and related notions (disciplinary power, pastoral power, cynegetic power), this book traces a set of public health measures taken over the last two centuries to control epidemics. It underlines how the need to conserve virus strains in order to identify and anticipate their mutations has given rise to cryopolitics, a set of techniques aimed at suspending the living in order to defer death. The book then questions the emancipatory scope of this cryopolitics by examining interspecies solidarity built by the warning signals sent by animals to humans about coming threats, be they pandemics, natural disasters, or climate change. By blurring the boundaries between the wild and the domestic resulting from the process of domestication, the politics of zoonoses relies on sentinels who preserve the memory of signs from the past to prepare living beings for future threats by involving them in a common ideal.

Frédéric Keck is Research Director at the Laboratory of Social Anthropology at CNRS-Collège de France-EHESS.

This book examines how the Covid-19 pandemic can be described as a biopolitical crisis, taking into account a fact often overlooked by commentators: Covid-19 is a zoonosis, a disease transmissible between animal species. The Sars-Cov2 virus causing this respiratory disease circulated in bats before passing to humans under as-yet mysterious conditions, and it was transmitted from humans to other species, notably mink and deer. Building on Michel Foucault s revival of the term biopolitics and related notions (disciplinary power, pastoral power, cynegetic power), this book traces a set of public health measures taken over the last two centuries to control epidemics. It underlines how the need to conserve virus strains in order to identify and anticipate their mutations has given rise to cryopolitics, a set of techniques aimed at suspending the living in order to defer death. The book then questions the emancipatory scope of this cryopolitics by examining interspecies solidarity built by the warning signals sent by animals to humans about coming threats, be they pandemics, natural disasters, or climate change. By blurring the boundaries between the wild and the domestic resulting from the process of domestication, the politics of zoonoses relies on sentinels who preserve the memory of signs from the past to prepare living beings for future threats by involving them in a common ideal.

Opening: Covid-19 displayed as pandemic and zoonosis

If an anthropologist of the future were to curate an exhibition displaying how humanity has experienced Covid-19, in the way that anthropologists of the past have presented distant societies to European audiences in museums, she might choose four objects and four animal species, which would represent the “material culture” and “ethno-zoology” of humanity today. These objects and animals have indeed populated the imagination of contemporary societies during this pandemic, in ways that remain to be analyzed and understood. The Covid-19 pandemic led humans to globally disseminate objects that had appeared in different places over the past two centuries, standardizing them according to international norms and hybridizing them with more traditional techniques of epidemic control. But Covid-19 is also a zoonosis, i.e. a disease transmitted between different animal species, which explains why the virus that caused it was so unpredictable. Here, then, are four objects and four animals, accompanied by information that might guide visitors through this exhibition.

A. Objects

- – The respirator. Covid-19 is a respiratory disease, which first infects the lungs, with secondary symptoms in the nervous system such as loss of taste or fatigue, grouped together under the term “long Covid.” Patients with severe respiratory symptoms, such as choking, were treated in intensive care hospital wards, using respirators to ventilate them artificially. These machines, which involve heavy interventions on the bodies of patients who must be regularly turned over and may be placed in an artificial coma, require the constant presence of nursing staff at their side. In times of emergency, hospital space must be reorganized to accommodate these priority patients. These techniques take over from the “iron lungs” invented in Boston in 1928 to combat poliomyelitis, benefiting from advances in artificial respiration in aviation during the twentieth century. The production of artificial respirators, whether rudimentary or high-tech, was greatly accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic.1

- – The mask. Initially a protective tool for hospital staff, the “surgical mask” spread to the entire population to protect against the transmission of Covid-19 by capturing droplets from the mouth and nose. Mainly worn in public transport and enclosed public places, where it was sometimes imposed by governments through sanctions, it was also worn in intimate spaces, with some people reluctant to remove their mask in front of others for reasons of precaution or modesty. It has thus profoundly redefined what it means to be a person (the term persona designates the mask in Latin Antiquity) confronted with the threat of respiratory disease circulating in the atmosphere shared by humans. Manufactured industrially from plastic or more traditionally from textile, it has become one of the waste products of contemporary societies, raising new issues of recycling. An archaeologist of the future may find that the only trace of this pandemic is an increase in the layer of plastic produced by humans since the middle of the twentieth century. Indeed, thanks to the invention of the plastic surgical mask in the 1950s, this piece of cloth, introduced into hospitals in Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, and imposed in the public arena after the work of Chinese physician Wu Liande on pneumonic plague in 1910 and on the occasion of the Spanish flu of 1918, was transformed into an industrial product, in such a way that the stockpiling of masks for hospitals became a criterion for evaluating a modern state.2

- – The vaccine. Covid-19 is an infectious disease caused by a virus called SARS-Cov2. In the absence of antiviral treatment for those who were already infected, and despite the hopes raised by advocates of hydroxychloroquine or artemisinin, vaccinating the uninfected population was the best public health strategy for curbing the pandemic, since it put an end to “stop-and-go” policies alternating lock-down and release of the population. The speed of vaccine production by pharmaceutical laboratories in Europe and North America, using the latest messenger RNA technology, surprised all observers and revived mistrust of vaccination, which has been a major trend on both continents over the last thirty years. The development of an inactivated vaccine by the pharmaceutical industries in Russia and China, less effective than messenger RNA vaccines but easier to distribute, and the World Health Organization’s calls for international solidarity under the Covax initiative, making vaccines a “common good of humanity,” have raised hopes on the possibility of sharing them with the countries of the South. The global distribution of a Covid vaccine offers a glimpse of a world in which SARS-Cov2 would be eradicated, but doses of vaccine would have to be manufactured regularly to respond to mutations in the virus. Two hundred and twenty years after its invention by Edward Jenner, and one hundred and forty years after its extension by Louis Pasteur, the vaccine, a pharmaceutical product supervised by the state and distributed to citizens as part of mass campaigns, has thus become an essential component of public health policies to combat pandemics.3

- – The cell phone. This is a new public health tool linked to the digitization of contemporary societies, whereas the other three objects have been used to control epidemics for at least a century. Through applications containing barcodes, it can summarize data on individuals (their infection by the virus, their different doses of vaccine) and inform them about potential virus carriers in their environment. During the Covid-19 pandemic, this application enabled individuals to make more informed decisions about their travels, and it allowed public authorities to monitor these travels. As a dematerialized version of the tracing policy chosen by certain countries to limit the pandemic as an alternative to confinement and vaccines, it is indissociable from the more rudimentary materiality of the test, a cotton swab that individuals have to insert into their orifices to find out if they are carriers of the virus. These applications and tests found a particularly well-developed form in China’s “zero-Covid policy,” reinforcing measures to control the population movements and to measure “social credit” that were already in place before the Covid-19 pandemic.4

B. Animals

- – The bat. Coronaviruses very similar to those causing Covid in 2019 have been found among rhinolophids in southern China and Southeast Asia. While it had been known since the 1950s that bats could transmit rabies through their bite – which remains exceptional for certain so-called “vampire” species in South America – it was discovered in the 1990s that they were also transmitting new viruses called Hendra and Nipah to humans in Australia and Southeast Asia, through horses, pigs, or fruit they had infected. The emergence of SARS-Cov1 in China in 2002, causing the epidemic of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), was explained with certainty by the transmission of a coronavirus – whose mild forms had until then been studied by veterinarians in pigs – from bats in southwest China to civets consumed in major cities such as Guangzhou. Two recent phenomena are mentioned to explain that new viruses are emerging in bats: deforestation, forcing bats to move to trees closer to human habitats, and new breeding practices for horses and pigs, bringing them closer to the forests and caves where bats breed, thus multiplying the number of intermediate species between bats and humans, and therefore the opportunities for their viruses to be transmitted to new species. Over the last forty years, it has been discovered that bats harbor a large number of viruses that are potentially dangerous to humans, due to their unique characteristics: they make up a quarter of all mammalian species, they live in dense multi-species colonies where they exchange large numbers of viruses that constantly cross species barriers, and they have developed immune defenses that enable them to withstand the metabolic cost of flight, notably a microbiota of restricted size and mechanisms for repairing the chromosomes carrying their genetic information.5

- – The pangolin. The identification of bats as reservoirs of coronaviruses left aside the question of the intermediate animal that transmitted SARS-Cov2 to humans. In April 2020, Chinese authorities suggested that the pangolin might be the intermediate animal between bats and humans, after viruses close to SARS-Cov2 were found by Chinese researchers in Malaysian pangolins.6 This discovery turned the attention of health authorities and the media to the international traffic of pangolins, whose scales are consumed in traditional Chinese medicine as a remedy for fevers. The International Union for Conservation of Nature banned the sale of Asian pangolins in 2000, which redirected international pangolin trafficking to Africa. The pangolin is thus an indicator of the transformation of a traditional hunting practice into a prestige consumption practice organized by an international market, which can go as far as new breeding practices of wild animals to supply new forms of traditional medicine. But the pangolin was an emblematic species for conservation in China for the last twenty years, which may explain that it was brought on the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.5.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Archäologie |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | animals • Anthropology • are pandemics caused by viruses that spread from animals to humans? Can animals warn us about coming threats? • Biopolitics • Coronavirus • Covid • Covid-19 • cryopolitics • Epidemic • Foucault • Global Pandemic • human-animal relations • Pandemic • Public Health • Sentinels • Vaccine • Variants • Virology • Virus • viruses that jump from animals to humans • warning signals • Zoonoses • zoonotic |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6689-9 / 1509566899 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6689-1 / 9781509566891 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 418 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich