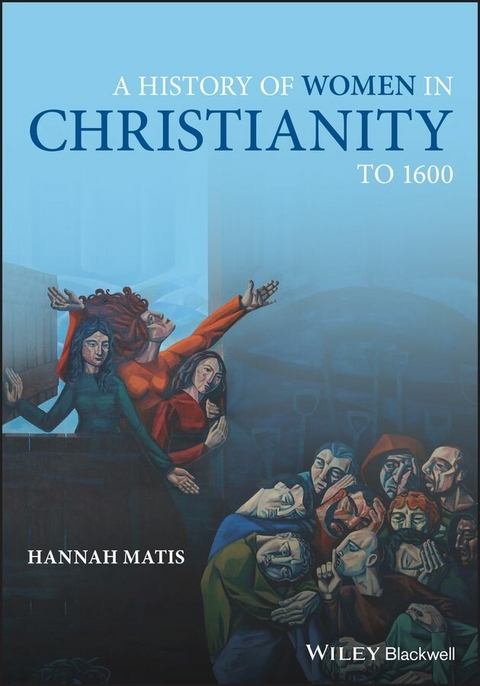

A History of Women in Christianity to 1600 (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-75663-7 (ISBN)

An overarching history of women in the Christian Church from antiquity to the Reformation, perfect for advanced undergraduates and seminary students alike

A History of Women in Christianity to 1600 presents a continuous narrative account of women's engagement with the Christian tradition from its origins to the seventeenth century, synthesizing a diverse range of scholarship into a single, easily accessible volume. Locating significant individuals and events within their historical context, this well-balanced textbook offers an assessment of women's contributions to the development of Christian doctrine while providing insights into how structural and environmental factors have shaped women's experience of Christianity.

Written by a prominent scholar in the field, the book addresses complex discourses concerning women and gender in the Church, including topics often ignored in broad narratives of Christian history. Students will explore the ways women served in liturgical roles within the church, the experience of martyrdom for early Christian women, how the social and political roles of women changed after the fall of Rome, the importance of women in the re-evangelization of Western Europe, and more. Through twelve chapters, organized chronologically, this comprehensive text:

- Examines conceptions of sex and gender tracing back their roots to the Jewish, Hellenistic, and Roman culture

- Provides a unique view of key women in the Church in the Middle Ages, including the rise of women's monasticism and the impact of the Inquisition

- Compares and contrasts each of the major confessions of the Church during the Reformation

- Explores lesser-known figures from beyond the Western European tradition

A History of Women in Christianity to 1600 is an essential textbook for undergraduate and graduate courses in Christian traditions, historical theology, religious studies, medieval history, Reformation history, and gender history, as well as an invaluable resource for seminary students and scholars in the field.

HANNAH MATIS is Associate Professor of Church History at Virginia Theological Seminary, Alexandria, Virginia, USA. Her areas of expertise include Carolingian biblical interpretation, late antiquity and medieval history, Reformation history, Anglican studies, the history of spirituality, and the religious experience of women within the Christian tradition. She is the author of The Song of Songs in the Early Middle Ages (2019).

HANNAH MATIS is Associate Professor of Church History at Virginia Theological Seminary, Alexandria, Virginia, USA. Her areas of expertise include Carolingian biblical interpretation, late antiquity and medieval history, Reformation history, Anglican studies, the history of spirituality, and the religious experience of women within the Christian tradition. She is the author of The Song of Songs in the Early Middle Ages (2019).

1

A History of Women in Christianity: An Introduction

I argue below that the writing of history must come to terms gracefully with the incomplete, that it must be a conversation open to new voices, that its essential mode is a comic one. I suggest that the pleasure we find in research and in storytelling about the past is enhanced both by awareness that our own voices are provisional and by confidence in the revisions the future will bring.

Caroline Walker Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion

In the 1130s, a man wrote to the mother of his child with an early attempt at a history of women in Christianity. Women have a special and favored status in the church, he argues, “For if you turn the pages of the Old and New Testaments you will find that the greatest miracles of resurrection were shown only, or mostly, to women, and were performed for them.” The man was the scholar Abelard; the woman was the learned Héloïse, his lover and his wife (Abelard and Héloïse 2003, pp. 56–62). After the brutal assault and castration of Abelard instigated by Héloïse's uncle, however, whatever hopes they may have had of the marriage were in ruins. Both had taken monastic vows, Abelard had buried himself in his teaching, and they had not seen one another for a decade. When they did meet again, it was in the midst of moving Héloïse's community of nuns to Abelard's new experiment in monastic life, the oratory of the Paraclete, and it is entirely possible, even likely, that they had had no real time to speak about the past.

When Abelard publicized their story, however, in an open letter now known as the History of My Calamities, Héloïse wrote to him, ostensibly requesting an account of his welfare. Her first letters represent the distillation of 10 years of unresolved grief, sexual frustration, and despair. They are also a hopeless and impossible demand for her former husband, and their former life, to return. Abelard's reply, his small history of women in Christianity, is both an apologia for women's status within the church and an attempt to console his distraught partner in reform. But it also was an effort to manage the strength of Héloïse's emotions, even to control them, by her husband‐turned‐spiritual director. Certainly to Héloïse, Abelard's deliberately detached response felt like avoidance: she took monastic vows first, she bitterly reminded Abelard in her answering letter, but not because she was aware of a shred of religious vocation in herself at that time. She did it for him.

The exchange between Abelard and Héloïse, nearly nine hundred years ago, neatly encapsulates one of the chief dilemmas in writing a history of women in Christianity: to what extent is the creation of any narrative history of this kind just one more effort, however well‐intentioned, at the appeasement and control of women within and by a patriarchal religious tradition? Even if, or precisely insofar as, the history of women in Christianity is an uplifting story, to what extent does it remain, in the poet Audre Lorde's famous phrase, a master's tool which cannot dismantle the master's house? Even if one recognizes the extent to which Christianity, historically, has been not only an opiate, as Marx believed, but the refuge of the oppressed and a crucible for resilience and political resistance, has that also been true for women? What does one make of churches and religious spaces overwhelmingly inhabited, supported, and maintained by women, yet which deny women positions of leadership and authority and have often exploited women's faith, hope, and love? There are no straightforward answers to these questions, and it is not always clear that they can even be answered or addressed satisfactorily by a book of this kind, but they have framed and shaped this project from its conception and at every stage of its development (Murray 1979; Grant 1989; Douglas 2005; Hayes 2011; Turman 2013; Walker‐Barnes 2014; Jennings 2020; Pierce 2021).

On a very basic level, this book attempts to name the names of women in the Christian tradition – significant figures, but also, in some cases, the only names we have – and survey them in roughly chronological order, from the origins of Christianity through the Reformation, ending at the seventeenth century. It attempts, first and foremost, to situate women within the particularity of their regional and historical context. It aims thereby to give the reader a sense of the normative experience of the ordinary laywoman, from whom, not least, so many of us trace our biological descent. This also creates a baseline against which the achievements of the extraordinary individual might be better understood. Particular attention is given to those women who were able to write, but a historical survey of this kind is also able to be generously inclusive about non‐literate women, as well as those women in the church whose achievements were political, institutional, and administrative rather than more obviously “religious.” In the premodern world, “church” and “state” were not separate or even clearly defined categories, and certainly were not experienced as such by ordinary people; this book ends exactly when such modern definitions and distinctions were coming into being. As one enters the early modern period, both the quantity and the quality of historical sources changes. There are more glimpses of non‐aristocratic women who are neither royal nor canonized in the documentary record, and more non‐textual sources survive to illustrate the rhythms of women's daily lives. In the last two chapters in particular, therefore, I have had to be particularly selective about whom and what to include for the sake of clarity, at exactly the moment when a broader field of choice exists.

It is virtually impossible, of course, for a single book to be completely comprehensive, not least because new discoveries continue to be made into the present moment. It is equally impossible to give equal, and sometimes even sufficient, treatment to everyone. Necessarily this is a work of synthesis, building on the meticulous scholarship of recent years, some of it very recent indeed. In the last 20 years in particular, interest in, and the pace of research on, women in the Christian tradition has increased to an exponential degree. Nevertheless, within the academy, much of this work is comparative and thematic in nature, and is often divided between scholars of early and world Christianity, Late Antiquity, the European Middle Ages, and the early modern world. The differing perspectives of history and theology, the nature of historical periodization, the selective lens of confessional history, not mention the numerous languages of both primary and secondary sources and the cost and availability of academic books and articles beyond research libraries, have all contributed to a situation in which much of this scholarship is unknown in the wider church and difficult to navigate for the beginning student. Where possible, I have referred to translations in English of the primary sources discussed here, which in turn can direct the student to the best critical editions of the primary sources available in their original languages. With some exceptions, the secondary scholarship cited in these pages is, likewise, in English, not because this represents anything like an exhaustive account of what exists, but because this book is intended as an introductory resource.

Particularly in recent years, there have been several efforts to provide broad surveys of women in Christianity across the whole of its history, including treatments specifically of nuns and religious women (Kavanagh 1852; Tucker and Liefeld 1987; McNamara 1996; Malone 2001–2003 ; MacHaffie 2006; Pui‐lan 2010; Moore 2015; Tucker 2016; Muir 2019). There are also more specialized works which concentrate on women's religious experience within discreet historical periods (Parks et al. 2021; Cooper 2013; Cohick and Hughes 2017; Bitel and Lifshitz 2008; Dronke 1984; Stjerna 2009). Out of necessity, broad treatments must be selective; likewise, they often adopt a thematic approach to this material, which tends to flatten and decontextualize women's historical experience, particularly across wide swathes of time. On the other hand, surveys which distinguish between the ancient, medieval, and early modern world are always weakest at their edges, in times of disruption and transition; moreover, they often neglect the extent to which women adapted earlier models of devotion and forms of religious life to respond to immediate economic and social pressures. One era which has particularly suffered in both broad and topically focused surveys is the late European Middle Ages, often dismissed as decadent or chaotic, but which should be understood on its own terms as one of the most creative and transformational eras for women's vernacular devotion and in pioneering new forms of women's religious life. The influence of late medieval devotional practice was so pervasive it extended, in different ways, both to women evangelicals and to women in early modern Catholicism – praying in one's native language and praying the rosary, respectively – but this period should not be understood merely as a prelude to the Reformation.

In...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.12.2022 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Christentum | |

| Schlagworte | Christentum • Christianity gender history • Christian Life • Cultural Studies • Frauenforschung • Geschichte • Geschichte des Christentums • History • History of Christianity • Kulturwissenschaften • medieval religious history • women Catholic Reformation • women Christian church • women Christian doctrine • women Christian history • women Christian spirituality • women Christian theology • women Christian tradition • women Reformation history • women's studies |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-75663-4 / 1119756634 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-75663-7 / 9781119756637 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich