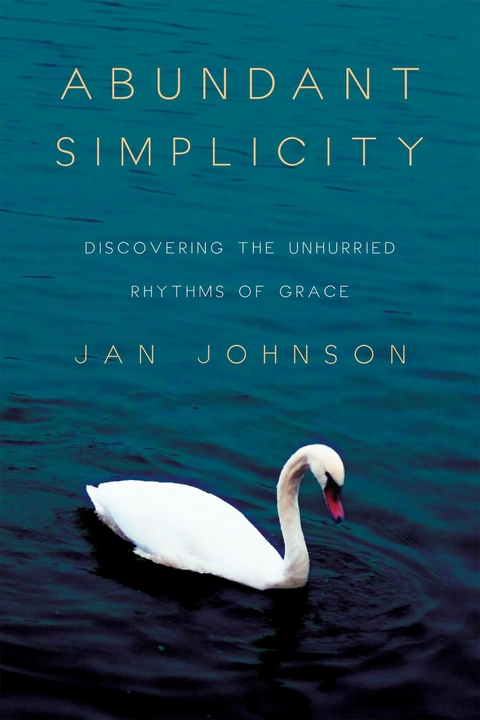

Abundant Simplicity (eBook)

173 Seiten

IVP Formatio (Verlag)

978-0-8308-6863-6 (ISBN)

Jan Johnson is a spiritual director and retreat leader living in the Los Angeles area. She has written a number of books including Invitation to the Jesus Life and Enjoying the Presence of God (both NavPress). Many of her articles are posted on her website: www.janjohnson.org.

Jan Johnson is the author of over twenty books and more than a thousand magazine articles and Bible studies. A speaker, teacher and spiritual director, she writes primarily about spiritual formation, social justice and living with purposeful intentionality. Her books include Abundant Simplicity, Hearing God Through the Year (editor), Enjoying the Presence of God, and the Spiritual Disciplines Bible Study Series. She holds a DMin in Ignatian spirituality and spiritual direction from the Graduate Theological Foundation and lives with her husband in Simi Valley, California.

2

Coping with Plenty

I have learned to be content with whatever I have. I know what it is to have little, and I know what it is to have plenty. In any and all circumstances I have learned the secret of being well-fed and of going hungry, of having plenty and of being in need.

Philippians 4:11-12

People marvel that the apostle Paul could be content while chained in a prison cell for years. This former Pharisee probably lived in filth and darkness, ridicule and loneliness. At best, his movements were restricted under house arrest by the Romans.

But it’s just as bewildering that Paul was content in times of plenty. When he stayed with rich folks such as Philemon or Lydia, he didn’t envy them or think, “Jesus was poor. Don’t they know that?” When he moved on from their homes to less opulent situations he didn’t think, “I sure do miss all that great food and the beautiful home.” He was truly content with whatever he had.

Contrary to what we usually think, having plenty does not make us content. Instead, a taste of plenty makes us want a little more than what we’ve got. When offered an increase in salary, who among us would say, “No thanks. I’m content with what I have. I don’t need a thing”?

We Want One Thing but Do Another

In a study on work, money and religion, sociologist Robert Wuthnow found that people feel worried about getting their personal needs met no matter how far up they are on the economic ladder. One person interviewed in his book said she earned a six-figure income but that it would take at least $50,000 more per year for her to live comfortably. Having plenty wasn’t quite enough to live comfortably.

Those of us who follow Christ are often unaware of how these appetites injure our life with God. “We live in a materialistic culture, and we want money and possessions, and very few people have heard a powerful voice telling them to resist those impulses, or how to resist those impulses. . . . Organized religion . . . has not done a good job of challenging people to examine their lifestyles.” Wuthnow found in interviews that religion is merely a therapeutic device designed to make people feel good about themselves. The church seems to have little to say about material consumption or self-indulgence.

Amid all this desire for more, however, many people also desire a simpler life, at least ostensibly. Take the magazine Real Simple, for example. While most new magazines fail, this one succeeded immediately. But a peek inside reveals pages and pages of advertisements and articles about new products—simplicity as a lifestyle to be purchased. The message is mixed: desire simplicity, but buy more stuff to get it.

We resemble the Roman god of doors and gates, Janus, who had two faces turned in opposite directions. In Janus’s case, this was an advantage so he could see the past and future at once. But our two faces represent divided minds as well; we desire a simpler life but we also think that the comfortable life we want can be acquired only by purchasing more things. Whichever face rules us in the moment seems to be unaware of the other. The I-need-more face cannot see that its arms are already full of activities and purchases.

Cultural Awareness

In our journey together in this book, I’ll describe common cultural messages about attractiveness, success and the so-called good life. I do this to help us become savvy about how these messages differ from the wisdom of our teacher, Jesus, and to subtly replace them with thoughts of treasuring God, investing our life in what God is doing and devoting ourselves to the good of other people.

The cultural messages described below—mostly about how success is defined as having more money, fame, power and status—are woven into our thoughts through exposure to the innumerable commercial messages that the average American experiences every day. Below are the assumptions behind those cultural messages. Their preeminence explains why we have to learn to be content. Consider reading these messages prayerfully and with openness, examining their inaccuracy but also observing if they have a sense of reality in your life.

More is better; bigger is better. As society pressures us to move forward and upward, we feel the need to continually upgrade: our computers, our education, our living space, the quality of our grass. Consider that a twenty-ounce soda, now commonplace, used to be enormous. In 1976, when 7-Eleven tested a thirty-two-ounce fountain drink at one of its locations, the store sold out of its entire thousand-cup stock in one weekend. Now a thirty-two ounce drink is small compared to the forty-eight- or sixty-four-ounce options. In the same way, the standard sizes of restaurant plates, television screens, outdoor grills and mattresses have increased without our noticing.

On a national level, we seek a continuously expanding economy, assuming that “the pursuit of self-interest will necessarily lead to ultimate social good,” as author Richard Foster says. But we’re discovering instead that the pressure of constant expansion often leads to the exploitation of both God’s world and other people through false advertising and ill treatment of workers, especially in developing countries by multinational corporations.

Busyness is a sign of power and significance. If someone tells us, “You’re always so busy,” they usually mean it as a compliment. Busy people are important people, and we’re supposed to be flattered. In our society it’s assumed that anyone who wants to get ahead must attend power lunches and strategic social events. These activities satisfy that drive that dictates to us—though we’re barely aware of it— I need to be noticed, to get attention, to move ahead.

All my desires must be fulfilled. When Thomas Jefferson wrote about the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness in the Declaration of Independence, he was thinking in terms of not being locked up for being in debt or for being a Baptist or a Quaker. But that phrase has morphed into the notion that we have a right to pursue whatever makes us happy. For people in developed countries, freedom is no longer about the absence of tyranny and oppression but about unrestricted freedom of choice: You have no right to stop me from doing whatever I want. As a result, people are mastered by their desires. The pursuit of happiness backfires, luring us to use people and love things.

The pursuit of happiness backfires, luring us to use people and love things.

We justify these actions through a deep-seated belief that our feelings must be satisfied. We even hear it said that to choose not to satisfy our desires is to warp our sense of self: I wouldn’t be me. This message stood out to me many years ago during a television show in which a woman (whose character I otherwise admired) advised her unmarried, unattached daughter something like this: “You’re just grouchy because you haven’t had sex lately.”

Think about that for a moment: According to this mindset, kindness isn’t possible without recent sexual experience. The mother believed that the daughter was harming herself by not satisfying her feelings. In this way of thinking, to resist feelings or to replace them with other feelings is out of the question. Feelings of lust and anger, in particular, are not only accepted but also applauded in movies, books and talk radio.

I Can’t Resist

The use of humor and sentimentality in advertising makes this deadly message of self-indulgence seem less harmful than it is—even funny or cute. Self-indulgence grows when we give in to excess, often by spending money or eating certain foods. We repeatedly give in until that activity becomes a settled behavior and we’re unable to resist gratifying even the smallest whim. Giving in to small, seemingly benign, culturally acceptable temptations leads to enslavement. People of faith are not exempt; those in whom the Word of God has been sown may find that the “care of this world . . . and deceitfulness of riches” choke out the life of God in them (Mt 13:22 kjv).

For example, I’ve always wondered how King David could commit adultery with Bathsheba and murder her husband when he lived such a faithful life overall; he was a man after God’s own heart (1 Sam 13:14). But while reading his whole story again recently, I saw that this evil didn’t come out of nowhere. For David’s entire adult life he practiced polygamy over and over in violation of God’s law, marrying six wives and keeping numerous concubines (2 Sam 5:13; 1 Chron 3:1). Every time he took a wife or concubine he gave into the enslavement of that inner voice: I must have her! Committing adultery (and having to cover it up) was the next logical step.

Self-indulgence is self-destructive. It destroys integrity one good intention at a time and eats away at the capacity to think about loving God and others. Self-indulgence invites us to be not only in the world, as Jesus was, but also of the world, with character and habits that look just like everybody else’s (Jn 1:10; 9:5; 17:11; 1 Jn 2:15-16).

Disciplines of simplicity are powerful because they move us away from self-indulgence just for today: don’t buy this one thing; don’t sign up for one more activity; don’t mention this last accomplishment to anyone. Even when we practice these restraints only temporarily, they still train us not to grab what we want...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.4.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Schlagworte | Christian • Energy • God • rhythm of life • Simple • Simple Life • Simplicity • Spiritual Formation • unhurried |

| ISBN-10 | 0-8308-6863-1 / 0830868631 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-8308-6863-6 / 9780830868636 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich