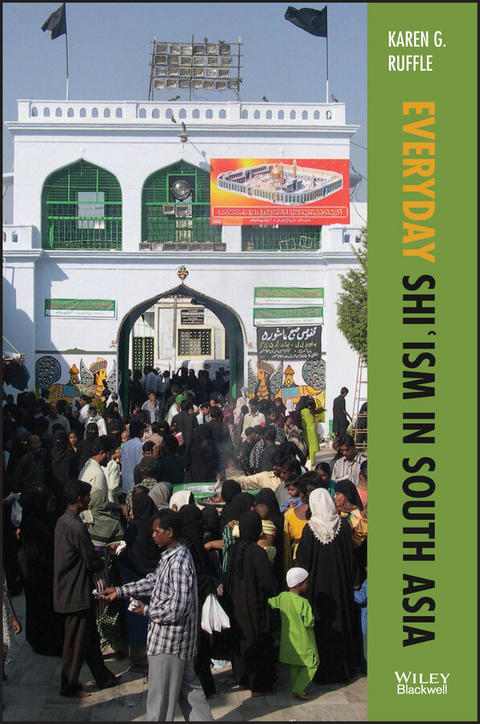

Everyday Shi'ism in South Asia (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-119-35715-5 (ISBN)

The first textbook to focus on the history of lived Shi'ism in South Asia

Everyday Shi'ism in South Asia is an introduction to the everyday life and cultural memory of Shi'i women and men, focusing on the religious worlds of both individuals and communities at particular historical moments and places in the Indian subcontinent. Author Karen Ruffle draws upon an array primary sources, images, and ethnographic data to present topical case studies offering broad snapshots Shi'i life as well as microscopic analyses of ritual practices, material objects, architectural and artistic forms, and more.

Focusing exclusively on South Asian Shi'ism, an area mostly ignored by contemporary scholars who focus on the Arab lands of Iran and Iraq, the author shifts readers' analytical focus from the center of Islam to its periphery. Ruffle provides new perspectives on the diverse ways that the Shi'a intersect with not only South Asian religious culture and history, but also the wider Islamic humanistic tradition. Written for an academic audience, yet accessible to general readers, this unique resource:

- Explores Shi'i religious practice and the relationship between religious normativity and everyday religious life and material culture

- Contextualizes Muharram rituals, public performances, festivals, vow-making, and material objects and practices of South Asian Shi'a

- Draws from author's studies and fieldwork throughout India and Pakistan, featuring numerous color photographs

- Places Shi'i religious symbols, cultural values, and social systems in historical context

- Includes an extended survey of scholarship on South Asian Shi'ism from the seventeenth century to the present

Everyday Shi'ism in South Asia is an important resource for scholars and students in disciplines including Islamic studies, South Asian studies, religious studies, anthropology, art history, material culture studies, history, and gender studies, and for English-speaking members of South Asian Shi'i communities.

Karen Ruffle, PhD, is Associate Professor in the Department of Historical Studies and the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto where she specializes in the study of South Asian Shi'ism. Her research and teaching interests focus on Shi'i devotional texts and ritual and material practices in South Asia. She is the author of Gender, Sainthood, and Everyday Practice in South Asian Shi'ism.

The first textbook to focus on the history of lived Shi'ism in South Asia Everyday Shi'ism in South Asia is an introduction to the everyday life and cultural memory of Shi i women and men, focusing on the religious worlds of both individuals and communities at particular historical moments and places in the Indian subcontinent. Author Karen Ruffle draws upon an array primary sources, images, and ethnographic data to present topical case studies offering broad snapshots Shi'i life as well as microscopic analyses of ritual practices, material objects, architectural and artistic forms, and more. Focusing exclusively on South Asian Shi'ism, an area mostly ignored by contemporary scholars who focus on the Arab lands of Iran and Iraq, the author shifts readers' analytical focus from the center of Islam to its periphery. Ruffle provides new perspectives on the diverse ways that the Shi'a intersect with not only South Asian religious culture and history, but also the wider Islamic humanistic tradition. Written for an academic audience, yet accessible to general readers, this unique resource: Explores Shi i religious practice and the relationship between religious normativity and everyday religious life and material culture Contextualizes Muharram rituals, public performances, festivals, vow-making, and material objects and practices of South Asian Shi'a Draws from author's studies and fieldwork throughout India and Pakistan, featuring numerous color photographs Places Shi'i religious symbols, cultural values, and social systems in historical context Includes an extended survey of scholarship on South Asian Shi ism from the seventeenth century to the present Everyday Shi'ism in South Asia is an important resource for scholars and students in disciplines including Islamic studies, South Asian studies, religious studies, anthropology, art history, material culture studies, history, and gender studies, and for English-speaking members of South Asian Shi'i communities.

Karen Ruffle, PhD, is Associate Professor in the Department of Historical Studies and the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto where she specializes in the study of South Asian Shi'ism. Her research and teaching interests focus on Shi'i devotional texts and ritual and material practices in South Asia. She is the author of Gender, Sainthood, and Everyday Practice in South Asian Shi'ism.

Introduction

On a bright, sunny day in Hyderabad’s Old City during Muharram in 2005, I was in the lane leading to the house of my mentor, the late Dr. Sadiq Naqvi, a historian of Persian literary and cultural history at Osmania University, as well as a renowned orator (zakir; “one who remembers”) in the Muharram mourning assemblies. On the long, white‐washed wall off Alava‐e Sartauq Mubarak ʿashurkhanah, a centuries‐old building where the metal standard containing a piece of the shackle that was placed around the neck of Imam Zain al‐ʿAbidin – the only male survivor of the battle of Karbala, Iraq in 680 CE – is displayed throughout the year, I saw hanging a massive, black banner, so rich in visual and verbal detail that it stopped me in my tracks to stare at it for several minutes.

The tableau presented by the banner, its subsidiary banners projecting below, as well as the artfully placed potted plants, compelled me to snap a photograph. Over the years, I have taken thousands of photographs of Muharram rituals, Shiʿi built space and devotional objects, and it is to the image of this banner that I return again and again (see Figure 0.01).

Each chapter of Everyday Shiʿism in South Asia is informed and inflected by elements of this banner, whether it is ʿAbbas’s ethic of care for family (represented by his severed arms and the arrow‐pierced waterskin), Qasem’s blood‐drenched name (representing his battlefield valor and commitment to protecting his faith, despite being a newlywed husband), Zainab, whose voice and testimony serves as inspiration for Shiʿi devotional literature, and Zainab’s young sons ʿAun and Muhammad (symbolized by two small water pots), who chose to fight like men on the Karbala battlefield while suffering terribly of thirst. The poet Millat’s couplets add an aesthetic touch to the banner, while amplifying the emotional effect of the verbal and visual images:

Figure 0.01 Muharram banner, Hyderabad. Photo by author, 2005.

On ʿashura morning, deep in thought and with a

Grieving heart, ʿAbbas must now show bravery.

Elsewhere on the banner Zainab speaks poetically of her half‐brother ʿAbbas’s valiant sacrifice, and we also hear her tone of righteous indignation at the humiliations suffered by her family:

When Zainab laid eyes on ʿAbbas’s arm,

She cried out, “Why not come, and cut the other, too?”

Another couplet encourages the devotee to consider the sacrifice of Imam Husain’s six‐month‐old son ʿAli Asghar, whose throat was pierced by an arrow:

Until we live in the path of ʿAli Asghar,

We shall only feel shame.

That an infant would give up his life for the cause of family and faith is intended to give pause, to reflect on one’s petty needs and concerns in the world.

This banner is not mere art, although it is certainly artistic. Nor is it simply a work of literary devotion to Imam Husain and the Ahl‐e Bait. Shiʿi cultural memory is encoded in this banner graphically and visually in ways that are legible for South Asian Shiʿa, using symbols and linguistic terms of reference that are resonant and spiritually meaningful. While an outsider may look at this banner and see dripping blood, severed arms, prison doors, and arrows, an insider to the tradition will immediately understand how these images are coded and to whom each representation points. ʿAbbas’s severed arms are viewed not with revulsion or fear by Shiʿa. Rather, they are viewed with a tremendous sense of love for his tender affection towards the children in the caravan suffering terrible thirst in the desert heat and deprived of water for three days. They remember ʿAbbas going on a suicidal mission to the banks of the Euphrates River to fill a waterskin, affectionately known as mashk‐e Sakinah in memory of his beloved niece and Husain’s youngest daughter, whose suffering he could no longer endure. The violence that is remembered is in relation to the caretaking ʿAbbas was doing for his family, particularly for the children who could not care for themselves, which brings tears to devotees in the mourning assemblies (majlis‐e ʿaza) during Muharram.

This banner reflects an important dimension of everyday Shiʿism through which Shiʿi devotion to the Imams and Ahl‐e Bait is grounded in emotional practices that mediate historical remembrance of the Karbala events, providing outlets for creative expression through ritual performances of the cultural memory of a violent act without violence. In Shiʿi cultural memory, the battle of Karbala was an act of shocking and horrific violence that was committed against the grandson and family of the Prophet Muhammad. It is through the shared cultural memory of the violence of Karbala, ritually performed through orations describing their suffering, the recitation of poetry in the mourning assembly, the display of devotional objects, and through the performance of highly structured forms of self‐flagellation (matam) performed with the hands and with instruments such as blades and chains, that individual and collective bonds of loyalty (walayah) and love (mahabbah) are reaffirmed each year.

Clifford Geertz’s “Notes on a Balinese Cockfight” offers useful insight into how we might further understand this banner and how it is emblematic of the ethos of the everyday Shiʿism I present in this book. In his ethnographic study of the cockfight in Bali, Geertz came to treat this ritual performance of a violent act without violence, considering it “as a text is to bring out a feature of it (in my opinion, the most central feature of it) that treating it as a rite or pastime, the two most obvious alternatives, would tend to obscure: its use of emotion for cognitive ends. What the cockfight says it says in a vocabulary of sentiment … Attending cockfights … is … a kind of sentimental education. What he learns there is what is his culture’s ethos and his private sensibility (or anyway, certain aspects of them) look like when spelled out externally in a collective text” (Geertz 1973, 449). The banner I photographed draws on key Karbala themes of sacrifice, suffering, violence, love, bravery, valor, kindness, faith, and generosity. This banner offers a microscopic perspective into the South Asian Shiʿi ethos and is a primer of religious sentiment.

The dense bundling of symbols and text on this Muharram banner demonstrates that for South Asian Shiʿa, memory of Karbala does not reside in an abstracted, remote past. While the event of Karbala happened in the historical past in 680 CE, its memory is embodied through social and cultural forms of production such as poetry, oratory, material objects, and built space. The banner is a mnemonic device, that is, it serves as a “reminding object” to help Shiʿa remember the panoply of Karbala events (Assmann 2015, 332). According to Jan Assmann, the forms that cultural memory takes are myriad and formalized as “narratives, songs, dances, rituals, masks, and symbols; specialists such as narrators, bards, mask‐carvers, and others are organized in guilds and have to undergo long periods of initiation, instruction, and examination” (2015, 334).

This book is about the contours of everyday life and cultural memory of Shiʿi women and men, which is shaped by visitations to the shrine‐tombs of saints, recitation of poetry, remembrance of the battle of Karbala, religious architecture and the devotional objects these buildings contain, festive events known as jashn, and different types of vows and votive offerings, all of which are inflected by perpetual devotion to the Imams and Ahl‐e Bait. The identities of these Shiʿa are also shaped by virtue of living in South Asia, by rank and status (whether one is sayyid or not), by the languages they speak, such as Urdu, Bengali, Sindhi, Telugu, Panjabi, or a range of other regional languages, and territorial affiliation to diverse locales, including Chennai, Ladakh, Kohat, Rampur, or Cambay. The vicissitudes of the 1947 Partition of the subcontinent into the postcolonial nation‐states of India and Pakistan have further molded Shiʿi identities in the modern period. For Pakistani Shiʿa, one’s status as a migrant citizen (muhajir) who came to the Muslim state from Lucknow or Delhi or elsewhere in India in the mass movement of people across the borderland constitutes a discursive domain in which “local” vs. “foreign” practices are negotiated and debated.1

Everyday Shiʿism

This book focuses on the everyday religious worlds of Shiʿi individuals and communities at particular historical moments and places in South Asia. I draw many of my examples from Hyderabad and the surrounding region, where I have conducted fieldwork on Shiʿi history, ritual, and material practices since 2003. I do not intend to make Hyderabad “speak” for all of South Asian Shiʿism, however, this is a place where I have spent extended periods of time. I have also studied and conducted fieldwork in Lucknow, India, and in Islamabad, Lahore, and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.4.2021 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Lived Religions |

| Lived Religions | Lived Religions |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Islam |

| Schlagworte | Geschichte • Geschichte des Islams • History • history of islam • Islam • Religion & Theology • Religion u. Theologie • Shi'i India • Shi'i Pakistan • Shi'i rituals • Shi'ism history • Shi'ism India • Shi'ism material culture • Shi'ism Pakistan • Shi'ism practices • Shi'ism rituals • Shi'ism South Asia • Shi'ism subcontinent • Shi'ism textbook • Shi'i South Asia • Shi'i textbook |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-35715-2 / 1119357152 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-35715-5 / 9781119357155 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich