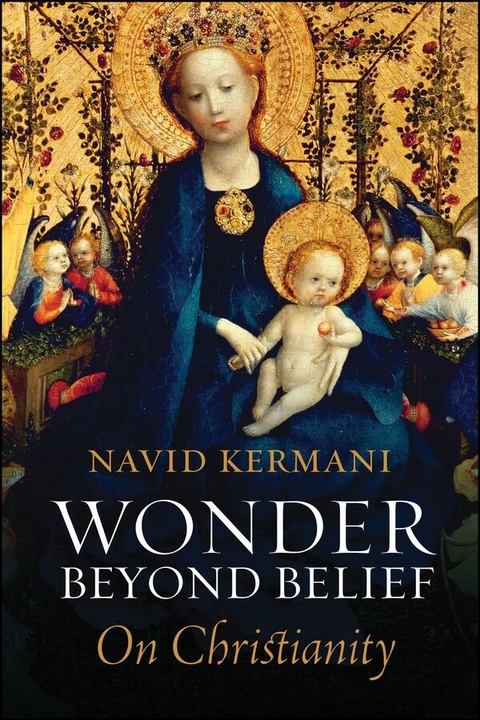

Wonder Beyond Belief (eBook)

241 Seiten

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-5095-1487-8 (ISBN)

What happens when one of Germany's most important writers, himself a Muslim, immerses himself in the world of Christian art? In this book, Navid Kermani is awestruck by a religion full of sacrifice and lamentation, love and wonder, the irrational and the unfathomable, the deeply human and the divine - a Christianity that today's Christians rarely speak of so earnestly, boldly and enthusiastically.

With the open-minded curiosity of a non-believer - or rather a believer in another faith - Kermani engages with Christian art in its great richness and diversity. The result is an enchanting reflection which reinvests in Christianity both its spectacular beauty and its terror. Kermani struggles with the cross, falls in love at the sight of Mary, experiences the Orthodox Mass and appreciates the greatness of St Francis. He teaches us to see the questions of our present-day lives in the pictures of old masters such as Botticelli, Caravaggio and Rembrandt - not with lectures on art history or theology, but with an intelligent eye for the essential details and the underlying relations to seemingly remote worlds, to literature and to mystical Islam.

Kermani's poetic school of seeing draws us in as we are carried along by his unique perspective on Christianity, rekindling our interest in great art at the same time. We are captivated by his unique and brilliant Islamic reading of the West.

Navid Kermani is a writer and scholar who lives in Cologne, Germany. He has received numerous accolades for his literary and academic work, including the 2015 Peace Prize of the German Publishers' Association, Germany's most prestigious cultural award.

What happens when one of Germany s most important writers, himself a Muslim, immerses himself in the world of Christian art? In this book, Navid Kermani is awestruck by a religion full of sacrifice and lamentation, love and wonder, the irrational and the unfathomable, the deeply human and the divine a Christianity that today s Christians rarely speak of so earnestly, boldly and enthusiastically. With the open-minded curiosity of a non-believer or rather a believer in another faith Kermani engages with Christian art in its great richness and diversity. The result is an enchanting reflection which reinvests in Christianity both its spectacular beauty and its terror. Kermani struggles with the cross, falls in love at the sight of Mary, experiences the Orthodox Mass and appreciates the greatness of St Francis. He teaches us to see the questions of our present-day lives in the pictures of old masters such as Botticelli, Caravaggio and Rembrandt not with lectures on art history or theology, but with an intelligent eye for the essential details and the underlying relations to seemingly remote worlds, to literature and to mystical Islam. Kermani s poetic school of seeing draws us in as we are carried along by his unique perspective on Christianity, rekindling our interest in great art at the same time. We are captivated by his unique and brilliant Islamic reading of the West.

Navid Kermani is a writer and scholar who lives in Cologne, Germany. He has received numerous accolades for his literary and academic work, including the 2015 Peace Prize of the German Publishers' Association, Germany's most prestigious cultural award.

I. MOTHER AND SON

MOTHER

SON

MISSION

LOVE I

LOVE II

HUMILIATION

BEAUTY

CROSS

LAMENTATION

RESURRECTION

TRANSFORMATION

DEATH

GOD I

GOD II

II. WITNESS

CAIN

JOB

JUDITH

ELIZABETH

PETER

JEROME

URSULA I

URSULA II

BERNARD

FRANCIS

PETER NOLASCO

SIMONIDA

PAOLO DALL'OGLIO

III. INVOCATION

VOCATION

PRAYER

SACRIFICE

CHURCH

PLAY

KNOWLEDGE

TRADITION

LIGHT

LUST I

LUST II

RECESSIONAL

ART

FRIENDSHIP

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

'An astonishing, deeply sympathetic, constantly surprising meditation on Christianity from one of the greatest Muslim writers and thinkers in the Western world. Kermani writes perceptively about individual works of art and particular places, about the New Testament, and about the rich traditions of Christian theology and practice. Still more important, he articulates a vision of Islamic-Christian friendship that is, in our vexed world, a human gift of rare importance.'

Stephen Greenblatt, Cogan University Professor of the Humanities, Harvard University

'In this beautifully written book, Navid Kermani performs something which, if not unprecedented, is still highly unusual, as he considers Christianity from the distance of a different faith. He does not claim any superiority here, quite the opposite. Unencumbered by the need to accept or reject, he explores the Christian faith with an alert interest and consuming curiosity. Through his keen gaze, coupled with a profound knowledge of theology and art history, Kermani captivates readers with the marvels of artworks that they might otherwise never really notice. The anglophone world needs and deserves this gem of a book.'

Daniel Boyarin, University of California, Berkeley

'In this book Navid Kermani draws on his unique perspectives as a Muslim intellectual to offer thoughtful reflections on the complex divine ideas underlying Christian art and the deep parallels that can be drawn between it and other traditions, including mystical Islam. As an outside observer of Christianity, Kermani reminds us that the great faith traditions have more in common than they have difference and how, at the end of the day, we all pay tribute to the same divine spirit. May more Muslim and Christian thinkers alike be inspired by his deep reflectiveness and willingness to engage across faith traditions.'

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed, Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies, American University, Washington, DC

'When I lived in Deir Mar Musa, Paolo Dall'Oglio would sometimes press a "very important" book on me to read. I am sure that Wonder Beyond Belief is one of these books. It encourages debate and impresses the reader with the need for communication and respect for other people's beliefs.'

Emma Loosley, University of Exeter

'In this beautifully written book, Navid Kermani performs something which, if not unprecedented, is still highly unusual, as he considers Christianity from the distance of a different faith. He does not claim any superiority here, quite the opposite. Unencumbered by the necessity to accept or reject, he explores the Christian faith with an alert interest and consuming curiosity. Through his keen gaze, coupled with a profound knowledge of theology and art history, Kermani captivates readers with the marvels of artworks that they might otherwise never really notice. The Anglophone world needs and deserves this gem of a book.'

Daniel Boyarin, University of California, Berkeley

Son

The boy is ugly. He is much uglier than he looks in this picture, or in any of the others that I have found on the Internet or taken myself with the good camera I borrowed. Clicking from one photo to the next, I would even go so far as to say that the boy is downright photogenic, when I remember how ugly he really looks. His mouth, for example, that open mouth: his receding lower and protruding upper jaw; and the lips more so: the lower lip short, or, more precisely, not short, but pressed, extruded into two fat bulges, accompanied by an upper lip pulled upwards like a tent on two strings, spreading out sideways to shelter the corners of the mouth. Because each picture captures only one point of view, they give no more than an inkling of how stupid the boy looks with his gaping lips – really stupid, more than just unbecoming: dimwitted, a mean kind of dimwit with something awkward and boorish about him at the same time, something of a spoiled brat thinking only of himself. It is unpleasant, unsavoury no less, to imagine a kiss, no matter how readily and easily we receive kisses from other children – but from him? There are children like that, five-year-olds who still scratch blithely in their unwiped bum crease and hold out their shit to you. This one has only lost some paint, but precisely on the three fingers that he holds up in blessing, and from the tip of his fingernails past the second knuckle. At first glance he seems about to stick his bent, brown fingers down your throat.

And how round he is – not fat in the sense of overweight, but rounded, his nose wider than it is long, his skin rotund like blown-up balloons. His cheeks look all the more spherical because the retracted lower lip lifts up his ball-shaped chin. In all, his face consists of three – no, four – no, five balls, because his double chin and the tip of his nose are also globular, but the spherical shape of his exaggerated bulk is what you can’t see if you look at the boy from a single point of view, that is, in only two dimensions. The two breasts are likewise round, like a woman’s, I notice looking at photos of the boy, and the fat encircles his upper and lower arms, forming more balls. A cherub, a mother would call him, believing her child the most beautiful on earth even if he is a paragon of hideousness to anyone else, especially an unbeliever or a believer in a different faith like me. My Catholic friend, whom I asked to go by the Bode Museum on his next visit to Berlin because, in the photos I had sent him, the boy’s stupidity is only twodimensional, my friend too conceded on the phone that the last thing he would associate with the boy was beauty, grace, charm.

‘Did you see his fingers?’

‘I’m standing right in front of him,’ my friend whispered.

He had no trouble finding the boy; he just asked the first guard he saw where to find the ugly Christ Child and was shown the way with a grin. All the guards knew it: Fatty is down the corridor to the hall under the smaller cupola, then first door on the left. In the catalogue, meanwhile, there is no illustration of the Christ Child, and even the special catalogue of the sculpture collection contains only a small, almost tiny photo, flatteringly lighted, as if the museum’s directors were ashamed of it or did not want to cause any trouble by a kind of blasphemy. Although blasphemy no longer bothers anyone in Berlin, except perhaps some of the Turks. But this boy, and this is the important thing to understand, praises the Father.

Christ Child, Perugia, c. 1320, nutwood, height: 42.2 cm. Bode Museum, Berlin.

The motif of Jesus as a child did not appear in Catholic art until the thirteenth century, my friend digresses, so the sculpture must be a very early, immature specimen. St Francis in particular loved the Christ Child, he explains, and female mystics cherished Him in contemplation and rocked Him in their arms, feeling themselves one with the Mother of God.

‘That snotface?’ I ask.

‘Well,’ my friend whispers. The sculptor of this particular piece, he supposes, which is perhaps less propitious to unio mystica, immortalized the features, and probably the dense curls, of his patron, or his patron’s child.

‘Aha,’ I say, just to say something in reply to his explanation, which doesn’t entirely satisfy me.

But my friend begs to be excused, he has to hang up, he just wanted to let me know. ‘Look it up in Ratzinger,’ he follows up in a text message. ‘I’ve read it,’ I answer.

I would rather have asked my friend more about St Francis, who didn’t mind the Son’s ugliness perhaps because he cherished every child, ugly or beautiful, as a child of God. Be that as it may, the retired pope, whom my friend esteems more highly than he does Pope Francis I, has not written a book about Jesus’ childhood. The years of Jesus’ childhood, when he was no longer an infant and not yet a youth, are omitted from the Infancy Narratives. Benedict XVI describes the annunciation of the birth, the birth itself, the visit of the three wise men, and the flight into Egypt – Jesus was still a baby then. Benedict XVI then continues the story only when Jesus is nearing adolescence. And in the meantime? He must know, the retired pope, that there are indications: the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Although it was not included in the canon, Christians gave it consideration as a testimony for many centuries.

Without entering into the philological controversy, I always found the Infancy Gospel to be a very realistic text. Precisely because it is disturbing, because it deviates very unfavourably from the notion we form, believing or unbelieving, of the adult Jesus, its conservation and propagation among Christianity would be plausible only by means of a particularly strong chain of transmission. For I never found the Infancy Gospel to be logically consistent, of a piece, with the beloved infant and the so fiercely loving later man. Playing on the bank of a stream, for example – and this is the bang that opens the book – the five-year-old diverts its rushing waters into little puddles by the sheer power of his will. A neighbour boy takes a willow switch and sweeps the water back into the stream. The two quarrel, and up to here it reads like a normal story: a scene between two boys that could happen in any kindergarten. But then Jesus cries out that the neighbour boy should wither up like a dead tree, never to bear leaves or roots or fruit again. And immediately the neighbour boy withers up completely, which can only mean he dies, he dies a wretched death, plunging his parents into sorrow, as the Infancy Gospel explicitly says. Jesus, unmoved, goes home.

And the account continues, in exactly that style, with those character traits: in the village, a boy running accidentally bumps Jesus’ shoulder. What does Jesus do? Kills the boy with a single word. And when the parents of this and the other boy, and more and more people, complain to Joseph – what does Jesus do? Strikes them all blind. And when his knowledge exceeds that of his teacher Zachaeus, he makes a laughing stock of the old man in front of everyone; Zachaeus despairs and wants to die on account of this child, who must be a paragon of hideousness.

Perhaps Benedict XVI, and my Catholic friend along with him, are too spellbound by the beauty they seem to find so important in Christianity, and hence in Jesus Christ, to see the ugliness as well. I understand their persistence; in a city like Berlin I need only attend a simple Sunday service to concur with them that beauty is sorely lacking in Christianity today. Poverty alone can’t make a God great. But beauty can only be realized together with its opposite. Jesus himself said, or is said to have said, in a saying transmitted by the Church Father Hippolytus, ‘He who seeks me will find me in children from seven years old.’ That would seem to mean that the Saviour is not to be found in the five-year-old that the Infancy Gospel describes. It means that even the Son must first become that which, in the canonical tradition, he is from the beginning. Jesus may have been a snotface, a monster of a child, one who possessed miraculous powers yet used them with malice. I am afraid some will think I am now blaspheming against Jesus himself. But it is no blasphemy, and malice is an attribute that is ascribed to God too.

Clicking from one picture to the next, I wonder whether it was not by remembering with shame the loveless child he had been that Jesus became filled with love, ultimately an ecstatic, enthusiastic, understanding man who emphasized the good even in a felon, who praised beauty even in what is ugly. This anecdote is a favourite of the Sufis, and also the one I love best: Jesus and his disciples come across a dead, half-decayed dog, lying with its mouth open. ‘How horribly it stinks,’ say the disciples, turning aside in disgust. But Jesus says, ‘See how splendidly its teeth shine!’ Jesus might have been speaking not only of the dog but also of the child he used to be.

But the mother – you couldn’t wish it on any mother to have such a son: announced by angels, exalted by kings, and then he turns out to be a spoiled brat brimming with supernatural power. The Infancy Gospel mentions Mary only at the very end, when Jesus is more than seven years old. She must have agonized over him, felt ashamed of his misdeeds, and yet stood by him, loving her cherub unconditionally. That is his...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.11.2017 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Tony Crawford |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Kunstgeschichte / Kunststile | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie | |

| Schlagworte | Art & Applied Arts • Art History & Criticism • Christentum • Christian art, art history, religious art • Cultural Studies • Cultural Studies Special Topics • Kulturwissenschaften • Kunstgeschichte • Kunstgeschichte u. -kritik • Kunst u. Angewandte Kunst • Religion • Religion & Culture • Religion & Theology • Religion u. Kultur • Religion u. Theologie • Spezialthemen Kulturwissenschaften |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-1487-2 / 1509514872 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-1487-8 / 9781509514878 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich