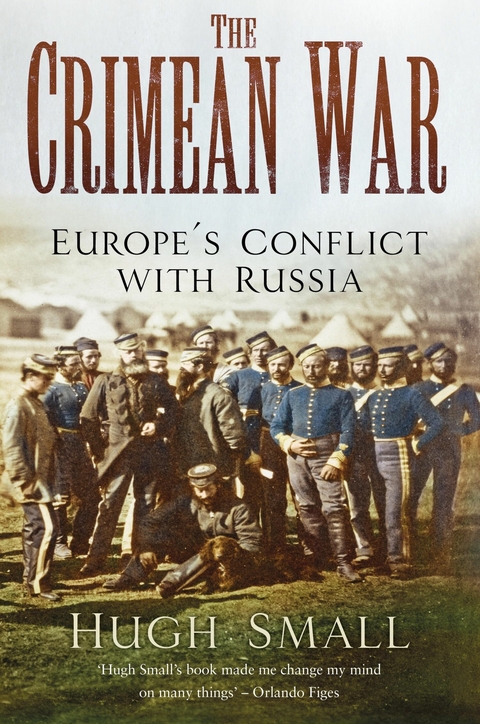

Crimean War (eBook)

240 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

9780750987424 (ISBN)

HUGH SMALL is the author of A Brief History of Florence Nightingale, and her Real Legacy, a Revolution in Public Health. He is an acknowledged expert on the war in the Crimea and has appeared on Channel 4 News, BBC2, Sky News and contributed to History Today on the subject. He lives in Central London.

In the winter of 1854, Britain and France, with Europe-wide support, invaded Russia and besieged the fortress of Sebastopol in the Crimea. Their object was to curtail Russian expansion. It was the most destructive conflict of the century, with total fatalities comparable to those of the American Civil War. Hugh Small, whose biography of Florence Nightingale first exposed the truth about her wartime hospital, now shows how the history of the Crimean War was manipulated to conceal Britain and Europe's failure. Only since the collapse of the Soviet Union has it become clear how much had been at stake in the Crimea. The failure of Britain's politicians to control their generals led to the collapse of the peacekeeping arrangements of the 'Concert of Europe' - a sort of early UN Security Council. Russian expansion continued unchecked, leading to the divisions seen today in Ukraine. Small is equally revealing about the battles. His carefully-researched account of the famous Charge of the Light Brigade overturns the modern conclusion that it was a blunder by senior officers. It was the ordinary cavalrymen who insisted on it - as the Commander-in-Chief admitted in parliament at the time.

HUGH SMALL is an acknowledged expert on the war in the Crimea and has appeared on Channel 4 News, BBC2, Sky News and contributed to History Today on the subject. He has also written Florence Nightingale: Avenging Angel, due to be reissued by Robinson in summer 2017. www.hugh-small.co.uk

3

From Phoney War to Invasion

EUROPE UNITES

The governments in London and Paris first sent their troops to Varna, in what is now Bulgaria, after the Tsar in April 1854 besieged the Turkish fortress of Silistria, on the south bank of the Danube. The Tsar found that his regional support was not as strong as he had expected. The inhabitants of the Balkans, oppressed by Turkish rule though they were, did not seem to relish being occupied by Russia. Their neighbours, the Austrians, had also become very hostile to the Russians and were mobilising a large army against them. The Austrians never declared war, but they ordered Russia to leave the territory they had occupied and signed an agreement with Turkey under which Austrian troops could drive the Russians out if necessary.

The first hostilities between Britain and Russia occurred in April, when the Royal Navy bombarded Odessa, but it was to be five months before the land armies would get to grips with each other. On 13 June the first Franco-British troops to reach the Balkans disembarked at Varna in Bulgaria only seventy miles from Silistria, close enough to hear the Russian siege guns. By mid-July there were 50,000 French, 60,000 Turkish and 20,000 British troops encamped among the lakes spreading inland from Varna. Also in attendance were the British and French fleets – the Royal Navy alone counting 25,000 sailors and 3,000 guns and affording a formidable protection and supply train for the army as long as the latter stayed near the coast. Further north there were 104,000 Turkish troops including the 20,000 besieged at Silistria.1

The Crimean theatre of war.

The French and British armies were very different. The French Army included conscripts, initially enlisted for three years and then placed in reserve and called up when required. The initial three-year enlistment was sufficient to give training in weapons and drill to every Frenchman who could not afford to pay a substitute, and the civilian reserve of former conscripts was the backbone of the French Army. In addition, some middle-class men joined the ranks voluntarily as the only way to progress to officer status in what was a respected profession. Pay was not high, opportunities for pillage were expected, and families sent money to their sons in the ranks rather than vice versa as in England. Britain prided itself in being nearly the only European state not to need conscription because it could afford to pay well. As a colonial power with far-flung manpower needs, a three-year enlistment would not have allowed enough time for transport and acclimatisation as well as a useful period in the colonies. Also, the reserve was not an idea in favour in Britain, where civilians with military training were seen as a threat to political order. In 1847 a Limited Enlistment Act allowed men to sign up for ten or twelve years, so the ranks were made up partly of the hard-core unemployed (among whom many were Irish) who had signed up for at least twenty-two years and partly of younger men who had signed up because of temporary hardship or a desire to see the world. Unlike the French, the British Army almost excluded the middle-class and neither officers nor men had much experience of management or commerce.2

The French officers were much more professional than their British equivalents, but the caricature of the rich young English swell in a loud check suit making jokes in Latin and mad on hunting is misleading. Many such officers existed, particularly at the start of the war, but it would be a mistake to think that when a man purchased a commission he acquired the power and responsibility that goes with that rank today. In the day-to-day business of the regiment nearly all the work was done by the non-commissioned officers, who were much more powerful than they are nowadays, assisted by the adjutant who was usually a commissioned former NCO. To a certain extent, junior officers were there for political, ornamental, and social reasons; that was the privilege that they purchased. Many officers joined up for a few years hoping their regiment would be sent to the Cape Colony, where the climate and the hunting were marvellous, and if a posting to the disease-ridden Indies fell to the regiment’s lot they made themselves scarce. As the Crimean War progressed, there was a high turnover of British officers. As conditions worsened, professional soldiers who were attracted by allowances that increased in proportion, and by the promotion lottery that accompanied a high mortality, tended to replace more affluent dilettantes who exercised their right to send in their papers and go home.

Another significant difference between the French and British was in supply strategy. The French Army traditionally lived off the land, while the British liked to supply their army by sea, from Britain if necessary. This difference had helped Wellington to defeat the French at Torres Vedras in the Peninsular War. Wellington had persuaded the friendly locals to burn their crops for miles around so that the French invaders starved while the Royal Navy fed Wellington’s army on biscuit baked in Woolwich. This difference, in the Crimea, was aggravated by the difference in pay levels. The British complained that the French stole everything available, or at best did not pay market rates but at a price they set themselves. The French would have been justified in complaining that the British, with their exorbitant pay, could force up prices or buy up everything and leave nothing for their impecunious Allies.

Such differences encouraged the two governments to keep the armies separate, under separate commanders, which did not help coordination on the battlefield. But at Varna in the summer of 1854 the armies shared a common problem – they could not get to the front because of a lack of baggage transport.

The plan had been that the British would engage local drivers with their carts at generous rates to carry the armies’ baggage the seventy miles or so inland to Silistria where they could help the besieged Turks. The problem was the local drivers, Bulgarians who disappeared as soon as they had received their first day’s pay. The Bulgarians did not like their Turkish masters, and were not fired by a patriotic desire to help their masters’ Allies. In fact rather than finding themselves on friendly territory as they expected, the Allies admitted that they were more like an ‘army of occupation’ helping Turkey to maintain a precarious presence in its disaffected provinces. The Commissariat couldn’t even get enough carts to deliver the beer ration to the disgruntled men camped eighteen miles from Varna.3 When the continued lack of baggage transport forced the army to remain idle, the cynics in it began to refer to themselves as ‘the army of no occupation’.

The weather was hot and oppressively humid. It sapped the officers’ enthusiasm for conducting repetitive drills and the men soon lost interest in the sports that were organised as an alternative. The powerful local raki had to take the place of Messrs. Barclay and Perkins’ porter and the sight of soldiers lying dead drunk beside the roads to the camp became commonplace. Flogging (which had recently been reduced in severity to avoid permanent disablement) was incapable of keeping the vice in check. Only activity and a sense of purpose could restore morale.

After a few weeks there was a new plan: the army would advance to relieve Silistria using pack horses for baggage transport, thus dispensing with the unreliable Bulgarian human element. It was estimated that 14,000 animals were needed, and buyers scoured the countryside for them. They had only acquired 5,0004 when the distant rumble of the heavy guns ceased: on 24 June the Russians abandoned their siege of Silistria in the face of strong Turkish resistance. The Turks then went on the offensive and attacked the Russians at Giurgevo in early July. On 25 June a British cavalry detachment was sent to the Danube to look for Russians but returned on 11 July without finding any. Two weeks later the Tsar ordered his generals to withdraw from all the occupied territories. Simultaneously, the French commander, Marshal St Arnaud, sent a sizeable force northwards to find and attack the Russians remaining in the Dobrudja, a region just south of the mouth of the Danube. This expedition was motivated partly by a desire to disperse the troops in the face of a cholera epidemic that had broken out in the Allied camps. However, the French took the sickness with them to the Dobrudja, and thousands died. They did not encounter the Russians, and their survivors returned to Varna in mid-August.

At this point, in August 1854, despite the failure of the expeditionary force to engage the Russians the politicians could justly claim a victory because the arrival of a multinational force in Turkey’s Balkan provinces had caused Russia to end the occupation. In the same month Austrian troops, with Turkey’s consent, began peacefully occupying the provinces from which Russia had withdrawn. They stayed there throughout the war as an international peacekeeping force, withdrawing soon after the war ended. British and French politicians could rightly claim that the Austrians would not have been so assertive if they had not sent the multinational force to the Balkans. It was an impressive trial and demonstration of Britain’s and France’s ability to forge an international coalition and to transport 70,000 men and their equipment to any coast in Europe.

It is hard to see how this deployment of British and French troops could have been avoided. It is...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.3.2018 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Black Sea • British Empire • Charge of the Light Brigade • Crimea • Crimean peninsula • crimea, russian empire, british empire, ottoman empire, french empire, second french empire, kingdom of sardinia, black sea, the black sea, crimean peninsula, sevastopol, turkey, sebastopol, florence nightingale, charge of the light brigade, ukraine, europe's conflict with russia • crimea, russian empire, british empire, ottoman empire, french empire, second french empire, kingdom of sardinia, black sea, the black sea, crimean peninsula, sevastopol, turkey, sebastopol, florence nightingale, charge of the light brigade, ukraine, europe's war with russia • europe's conflict with russia • Florence Nightingale • French Empire • Kingdom of Sardinia • Ottoman Empire • Russian Empire • Sebastopol • Second French Empire • Sevastopol • the Black Sea • Turkey • Ukraine |

| ISBN-13 | 9780750987424 / 9780750987424 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich