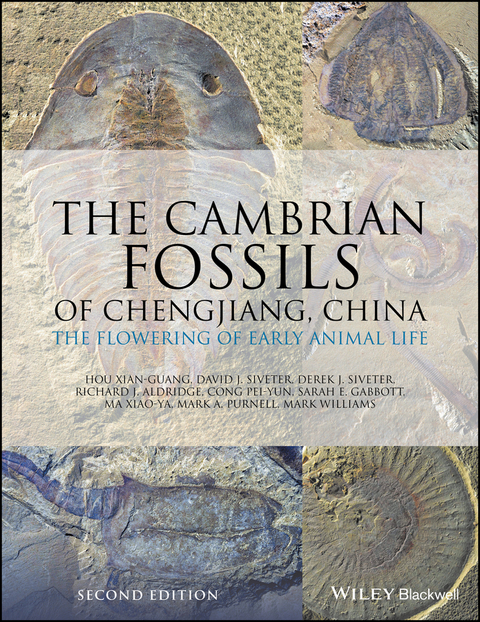

The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang, China (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-89626-6 (ISBN)

The celebrated lower Cambrian Chengjiang biota of Yunnan Province, China, represents one of the most significant ever paleontological discoveries. Deposits of ancient mudstone, about 520 million years old, have yielded a spectacular variety of exquisitely preserved fossils that record the early diversification of animal life. Since the discovery of the first specimens in 1984, many thousands of fossils have been collected, exceptionally preserving not just the shells and carapaces of the animals, but also their soft tissues in fine detail. This special preservation has produced fossils of rare beauty; they are also of outstanding scientific importance as sources of evidence about the origins of animal groups that have sustained global biodiversity to the present day.

Much of the scientific documentation of the Chengjiang biota is in Chinese, and the first edition of this book was the first in English to provide fossil enthusiasts with a comprehensive overview of the fauna. The second edition has been fully updated and includes a new chapter on other exceptionally preserved fossils of Cambrian age, exciting new fossil finds from Chengjiang, and a phylogenetic framework for the biota. Displaying some 250 figures of marvelous specimens, this book presents to professional and amateur paleontologists, and all those fascinated by evolutionary biology, the aesthetic and scientific quality of the Chengjiang fossils.

Hou Xian-guang is former Director, Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology, Yunnan University, Kunming

David J. Siveter is Professor Emeritus of Paleontology, University of Leicester

Derek J. Siveter is Professor Emeritus of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford

Richard J. Aldridge was Professor Emeritus and F.W. Bennett Professor of Geology, University of Leicester

Cong Pei-yun is Professor of Paleobiology, Yunnan University, Kunming

Sarah E. Gabbott is Professor of Paleobiology, University of Leicester

Ma Xiao-ya is Professor of Paleobiology, Yunnan University, Kunming, and the Natural History Museum, London

Mark A. Purnell is Professor of Paleobiology, University of Leicester

Mark Williams is Professor of Paleobiology, University of Leicester

The celebrated lower Cambrian Chengjiang biota of Yunnan Province, China, represents one of the most significant ever paleontological discoveries. Deposits of ancient mudstone, about 520 million years old, have yielded a spectacular variety of exquisitely preserved fossils that record the early diversification of animal life. Since the discovery of the first specimens in 1984, many thousands of fossils have been collected, exceptionally preserving not just the shells and carapaces of the animals, but also their soft tissues in fine detail. This special preservation has produced fossils of rare beauty; they are also of outstanding scientific importance as sources of evidence about the origins of animal groups that have sustained global biodiversity to the present day. Much of the scientific documentation of the Chengjiang biota is in Chinese, and the first edition of this book was the first in English to provide fossil enthusiasts with a comprehensive overview of the fauna. The second edition has been fully updated and includes a new chapter on other exceptionally preserved fossils of Cambrian age, exciting new fossil finds from Chengjiang, and a phylogenetic framework for the biota. Displaying some 250 figures of marvelous specimens, this book presents to professional and amateur paleontologists, and all those fascinated by evolutionary biology, the aesthetic and scientific quality of the Chengjiang fossils.

Hou Xian-guang is former Director, Key Laboratory for Palaeobiology, Yunnan University, Kunming David J. Siveter is Professor Emeritus of Paleontology, University of Leicester Derek J. Siveter is Professor Emeritus of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford Richard J. Aldridge was Professor Emeritus and F.W. Bennett Professor of Geology, University of Leicester Cong Pei-yun is Professor of Paleobiology, Yunnan University, Kunming Sarah E. Gabbott is Professor of Paleobiology, University of Leicester Ma Xiao-ya is Professor of Paleobiology, Yunnan University, Kunming, and the Natural History Museum, London Mark A. Purnell is Professor of Paleobiology, University of Leicester Mark Williams is Professor of Paleobiology, University of Leicester

The first edition of The Cambrian fossils of Chengjiang was a ?must have? book for palaeontologists. Now I am afraid you are all going to have to fork out for the second edition. After 13 years, this completely revised edition reflects the significant amount of research that has taken place over the last decade or more on the remarkable Chengjiang lagerstatte.

The fossil material of the Chengjiang lagerstatte is of course stuff to drool over and the envy of palaeontologists who have to deal with the more common forms of hard-part preservation. Over 30 species have been added to the taxonomic list, reflecting a greater understanding of the diversity and taxonomy of this biota, which now boasts a total of over 250 species. A significant number of these are still ?floating around? waiting for their systematic identity card so the Chengjiang case is far from being closed.

The discovery is now over 30 years old, being first found in 1984 by Hou Xian-Guang, who is still active and one of the authors of this new edition. Since the first edition was published, the site has been inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (in 2012) as a ?globally outstanding example of a major stage in the history of life, representing a paleobiological window of great significance?. As such, the 515-520 Ma Chengjiang biota complements Canada?s slightly younger, 505 Ma Burgess Shale biota. The latter is somewhat less diverse (c 120 known species) but has a similar ecological structure; consequently, the taxonomic similarities and differences between the two are of particular evolutionary interest and significance.

This second edition of The Cambrian fossils of Chengjiang is much more than a mere update. It provides an overview of the lagerstatte and the rapidly expanding literature on all aspects of its geology, much of which is in Chinese and otherwise difficult to access. The format of the book is larger and many of the photos are even better than before. The book would be a fine present for any palaeontologist - even if you have to treat yourself!

Reviewed by: Douglas Palmer

"The work is authoritative and highly illustrated; the high-quality illustrations were, and are, an immensely important aspect of the work. They show just how beauti-fully preserved these soft-bodied animals are and how, with the requisite skills, this extraordinary detail can be illustrated. It is essential that this book be on every paleo-biologist?s bookshelf."

- Paul Seldon, Priscum Summer 2018

"Very much like its predecessor, this book is bound to become a standard reference thanks to its very well contextualized introduction and really complete overview of the Chengjiang biota. Whether you are a natural science teacher, a specialist of the Cambrian Explosion, have an interest in palaeontology and evolution of early life, or you just like the weird diversity of forms in Cambrian animals, then this book is for you. I would recommend it to all palaeontologists and libraries, this is a must-have!"

- Vincent Perrier, Paleontology Association Newsletter, July 2018

1

Geological Time and the Evolution of Early Life on Earth

Our planet is some 4540 million years old. We have little record of Earth’s history for the first half billion years, but rocks have been found in Canada that date back some 4000 million years (Bowring & Williams 1999). There are yet older indications of the early Earth in the conglomerates of the Jack Hills of Australia, where tiny zircon crystals recycled from much older rocks give ages as old as 4400 million years (Wilde et al. 2001), and therefore their formation occurring a little after the birth of our planet. These zircons are important, because chemical signals within the crystals suggest the presence of water, a prerequisite for life on Earth, and also the lubricant for plate tectonics, which provides an active mineral and nutrient cycle to sustain life.

Because Earth’s history is so enormous from a human perspective, it has been divided up into more manageable packets of time, comprising four eons, the Hadean, the Archean, the Proterozoic, and the Phanerozoic (Fig. 1.1); the Hadean, Archean, and Proterozoic are jointly termed the Precambrian. In practice, the boundaries between these eons represent substantial changes in the Earth system driven by such components as plate tectonics, the interaction of life and the planet, and by the evolution of ever more complex biological entities. The boundary between the extremely ancient Hadean and Archean is set at about 4000 million years, whilst that between the Archean and Proterozoic is drawn at 2500 million years. The beginning of the Phanerozoic (literally meaning ‘manifest life’) is recognized by evolutionary changes shown by animals about 541 million years ago. The Archean is subdivided into the Eoarchaen (4000–3600 million years), the Paleoarchean (3600–3200 million years ago), the Mesoarchean (3200–2800 million years ago), and the Neoarchean (2800–2500 million years ago) eras. The Proterozoic is subdivided into the Paleoproterozoic (2500–1600 million years), the Mesoproterozoic (1600–1000 million years), and the Neoproterozoic eras (1000–541 million years). The earliest period of the Phanerozoic eon, the Cambrian, coined after the old Latin name for Wales, was a time that almost all of the major animal groups that we know on Earth today made their initial appearances in the fossil record. Some of the most important fossil evidence for these originations has come from the Chengjiang biota of southern China.

Figure 1.1 Some major events in the history of the Earth and early life.

However, the record of life on Earth goes back much further in time than the Cambrian Period, perhaps nearly as far as the record of the rocks. The early, Hadean Earth was subject to heavy bombardment by asteroids, many of which were so large that they would have vaporized early surface waters and oceans. This heavy bombardment ceased some 3900 million years ago, and from this period of the early Archean onwards there have been permanent oceans at the surface of planet Earth. Not long after – from a geological perspective – there is evidence for life. Microfossils of sulfur‐metabolizing bacteria are reported from Paleoarchean rocks as old as 3400 million years in Australia (Wacey et al. 2011), and there is circumstantial evidence from geochemical studies that carbon isotopes were being fractionated by organic processes as long ago as 3860 million years in the Eoarchean (Mojzsis et al. 1996). However, there is a need to treat some of the reports of evidence for very early life with caution, and the further back in time the record is extended the more controversial the claims become (see, e.g., Grosch & McLouglin 2014).

The sparse organic remains of the Archean are microscopic and sometimes filamentous. But there is also macroscopic evidence for early life, represented by microbial mat structures (Noffke et al. 2006) and stromatolites (Fig. 1.2). Modern stromatolitic structures are built up through successive layers of sediment being trapped by microbial mats. The resulting stromatolite forms are commonly dome‐like or columnar, and these characteristic shapes can be recognized in Paleoarchean sedimentary deposits up to 3500 million years old. Once again, the very oldest stromatolites are somewhat controversial, and it is possible that they could have been constructed by abiogenic processes rather than by living organisms (Grotzinger & Rothman 1996).

Figure 1.2 Representative fossils of the early history of life on Earth. (a) The trace fossil Treptichnus, burrows from early Cambrian strata in Sweden, signaling the movement of bilaterian animals through the seabed, ×1.5. (b) An Ediacaran acritarch, a probable resting cyst of a unicellular eukaryotic phytoplanktonic organism, ×1000; these were important primary producers in the Proterozoic and early Phanerozoic oceans. (c) Ediacaran organisms on a late Proterozoic marine bedding plane surface characteristic of Earth’s first widespread complex multicellular ecosystems; Mistaken Point, Mistaken Point Ecological Reserve, Newfoundland. The specimen upper center is about 20 cm long. (d) Late Proterozoic stromatolites, microbial mat structures; Bonahaven Formation, Islay, Scotland, see Estwing hammer for scale.

The microorganisms identified living in modern stromatolitic communities represent a wide range of types of life, including filamentous and coccoid cyanobacteria, microalgae, bacteria, and diatoms (Bauld et al. 1992). If we accept the combined evidence from microfossils, microbial mats, stromatolites and carbon isotopes, then it appears that life may have begun on Earth some 3500 million years ago, or possibly somewhat earlier, and that these life forms included microorganisms that could generate their own energy by chemo‐ or photosynthetic processes. Whether these earliest microorganisms used oxygenic photosynthesis – utilizing carbon dioxide and water to make energy and thereby releasing free oxygen – is controversial, and there is little evidence of a build‐up of oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere until much later. But by the boundary between the Archean and Proterozoic eons, 2500 million years ago, cyanobacterial microorganisms using oxygenic photosynthesis had certainly evolved. These are responsible for one of the key events in the evolution of the Earth’s biosphere, the Great Oxygenation Event between 2400 and 2100 million years ago. This event led to atmospheric levels of oxygen rising to about 1% of the current level, and it is evidenced by the disappearance of reduced detrital minerals such as uraninite (uranium ore) from sedimentary deposits younger than this age worldwide (Pufahl & Hiatt 2012). The oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere and hydrosphere was to have profound implications for the path of life. It provided new mechanisms of energy supply, and also pushed to the margins of existence in Earth’s earliest biosphere those organisms of the Archean that were adapted for an anoxic world and for which free oxygen was toxic.

There is a much richer and less controversial record of life in rock strata of Paleoproterozoic and Mesoproterozoic age. Microbial mats and stromatolites constructed by cyanobacteria are quite abundant, and it is likely that cyanobacteria had become diversified by the mid‐Paleoproterozoic (Knoll 1996). There are also fossil data showing that one of the most significant steps in evolutionary history had taken place by this time – the appearance of complex, eukaryotic cells (Fig. 1.2). Eukaryotes are distinguished from the more ancient prokaryotes by their larger size, and by their much more complicated organization, with a membrane‐bound nucleus containing DNA organized on chromosomes, and a variety of organelles within the cytoplasm. There are tell‐tale signatures in fossils that identify eukaryotes in Paleoproterozoic rocks. Prokaryotic cells such as bacteria can be large. They can have processes that project out from the cell, and they can have cell structures that preserve as fossils. However, no single prokaryotic cell possesses all of these characters, and neither do they possess a nucleus or the complex surface architecture of eukaryotes. Based on these pragmatic criteria, the first appearance of eukaryotes is seen in fossils from rocks in China and Australia about 1700 million years ago (Knoll et al. 2006).

Later still, during the Mesoproterozoic, came the origination of sex, with its ability to exchange genetic information and thereby increase the genetic variability of life, and the development of multicellular structures, with their ability for some cells to become specialized for different functions. Amongst the earliest multicellular and sexually reproducing organisms is the putative red alga Bangiomorpha, which lived in shallow seas some 1200 million years ago. It possessed specialized cells to make a holdfast for attaching to the seabed, and from its holdfast arose filaments composed of multiple cells, the arrangement of these cells being comparable to the modern red alga Bangia (Butterfield 2000).

The first metazoans (animals) arose during the Neoproterozoic. Typical metazoans build multicellular structures with cells combining into organs and specializing in different functions, such as guts, hearts, livers, or brains. However, probably the most primitive of metazoan organisms are the sponges, which build three‐dimensional structures that control the flow...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.3.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Archäologie |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Vor- und Frühgeschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Mineralogie / Paläontologie | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | animals fossils • Biota • Biowissenschaften • Cambrian age fossils • Cambrian Chengjiang biota • Cambrian Fossils • chengjiang • Chengjiang algae • Chengjiang biota • Chengjiang Biota paleoecology • Chengjiang Biota recorded species • Chengjiang Biota significance • Chengjiang fossils • Chengjiang fossils preservation • Chengjiang fossils taphonomy • Chengjiang Lagerstatte geological setting • China • early animal life • earth sciences • Evolution • evolutionary biology • Evolutionsbiologie • fossils • Geowissenschaften • Life Sciences • Paläontologie, Paläobiologie u. Geobiologie • paleontological discoveries • paleontologists • paleontology • Paleontology, Paleobiology & Geobiology • Phylum Brachiopoda • Phylum Cnidaria • Phylum Lobopodia • Phylum Nematomorpha • Phylum Porifera • Phylum Priapulida: Phylum Hyolitha • preserved Paleozoic faunas • The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang • The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang, China: The Flowering of Early Animal Life • who discovered Chengjiang Biota • yunnan province |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-89626-2 / 1118896262 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-89626-6 / 9781118896266 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich