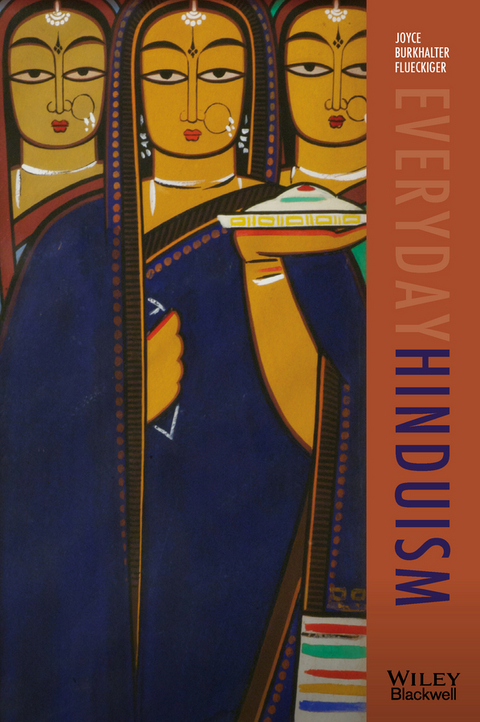

Everyday Hinduism (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-52818-1 (ISBN)

- Introduces and contextualizes the rituals, festivals and everyday lived experiences of Hinduism in text and images

- Includes data from the author’s own extensive ethnographic fieldwork in central India (Chhattisgarh), the Deccan Plateau (Hyderabad), and South India (Tirupati)

- Features coverage of Hindu diasporas, including a study of the Hindu community in Atlanta, Georgia

- Each chapter includes case study examples of specific topics related to the practice of Hinduism framed by introductory and contextual material

Joyce Burkhalter Flueckiger is a Professor in the Department of Religion at Emory University. She is the author of When the World Becomes Female: Guises of a South Indian Goddess (2013), In Amma's Healing Room: Gender and Vernacular Islam in South India (2006), and Gender and Genre in the Folklore of Middle India (1996).

Acknowledgements viii

A Note on Transliteration x

Map of India xii

Introduction 1

The Terms "Hindu," "Hinduism," and "Hindu Traditions" 2

Dharma: A Way of Life and Religious Tradition 3

Context and Multiplicity 6

Ethnographic Selection and Chapter Topics 9

A Note on Caste 13

1 Families of Deities 18

The Trimurti 20

Mythological and Narrative Families 21

Vishnu 21

Shiva 25

Devi, the Goddess 28

Gramadevatas, Village Deities 30

Temple Families 34

Ritual Families in Domestic Shrines 36

2 Oral and Visual Narratives and Theologies 46

Oral Performance Genres 47

Visual Narratives and Theologies 49

Verbal and Visual Together 56

Where Does the Narrative Lie? 61

The Ramayana Tradition Performed 62

3 Loving and Serving God: Bhakti, Murtis, and Puja 73

Bhakti, Devotion 73

Singing to God and the Goddess 76

Worshipping Deities in Material Form 77

Narratives of God in the Murti 80

The Deity without Form 83

Modes of Worshipping the Murti 85

The Services of Puja 89

Online, Cyber Puja 93

4 Temples, Shrines, and Pilgrimage 97

Temples 98

Sthala Puranas 99

Temple Architecture 101

Temple Worship 104

Shrines 109

Pilgrimage 110

Tirumala, a Southern, Pan?]Indian, and Transnational Pilgrimage Site 114

Narsinghnath, a Sub?]regional Pilgrimage Site 119

5 Festivals 123

Divali: Festival of Lights 127

Ganesha Chaturthi: Domestic, Neighborhood, and City?]Wide Celebrations 129

Place?]Bound Festivals: Tirupati's Gangamma Jatara 138

6 Vrats: Ritual Vows and Women's Auspiciousness 145

Temple Vrats 146

Domestic Vrats 147

Vrat Kathas: Ritual Narratives 150

Two South Indian Vrat Traditions 151

Gender and Vrats 164

7 Samskaras: Transformative Rites of Passage 169

Pregnancy and Birth 170

First?]Year Samskaras 171

Upanayana and Rituals of Transition to Adulthood 172

Ranga Pravesham: Ascending the (Dance) Stage 177

Marriage 178

Death Rituals 186

8 Ritual Healing, Possession, and Astrology 193

Accessing Multiple Healing Sites 194

Healing across Religious Boundaries 199

Possession 203

Astrology 211

Afterword 220

Glossary 227

Index 231

"An engaging read, as a textbook as well as general resource, this book has the potential to make instructors re-envision how they teach Hinduism in the classroom." (CHOICE, 2016)

"Flueckiger draws on her wide-ranging ethnographic work to vividly illustrate and critically appreciate the stories, rituals, and materials of an ancient, complex, and continuously evolving tradition and invites readers to engage both the past and the modern in fresh and respectful ways. Imaginatively conceptualized, sensitive to variation, context and change, and beautifully written, Everyday Hinduism evokes a wonderful sense of the people-centered plural worlds of Hinduism."

--Leela Prasad, Duke University

"Clear, deft, and beautifully proportioned, Everyday Hinduism is exactly what's been missing as a major textbook resource for an introductory course on Hinduism. I am thrilled to see it: a wish fulfilled!"."

--Professor John Stratton Hawley, Columbia University

"At last! Flueckiger's accessible introduction to contemporary Hinduism in practice could not be more welcome. This book successfully and respectfully illuminates dynamic interactions of deities, rituals, stories and ordinary people -- and promises to enhance understandings of a complex, multi-faceted religion for students from outside and inside Hindu cultural worlds.."

--Professor Ann Grodzins Gold, Syracuse University

Introduction

Many introductory textbooks on Hinduism begin with the historical roots of Hindu traditions, starting with the sacred texts of the Vedas, then proceed through a primarily textual history of Hindu traditions, through the Upanishads, the Ramayana and Mahabharata epics, and bhakti (devotional) poetry of the medieval and premodern periods.1 However, most Hindus do not experience or talk about their religious traditions along the trajectories of these kinds of textual histories. They may invoke the authority of what they consider to be “ancient texts” or “the old ways” and “custom,” but they also – and primarily – experience these as contemporary practices.

The ethnographic focus of this book is these everyday ritual and narrative practices of specific people in specific places. Such a perspective reveals the fluidity, flexibility, and creativity of Hindu practices as well as some broad structures and parameters that may cross and be shared across space and time. For most Hindus, what they do – what rituals they practice, the festivals they celebrate, who they marry, what they eat – matters more on a day-to-day basis than the philosophical concepts of karma, samsara, and moksha. So while these concepts will come up in the practices described in this book, they will not be its focus. The ethnographic approach to Hindu practices in this book is not intended to be a comprehensive study of Hinduism; rather, it presents one starting point and framework for the study of Hindu traditions and is complementary to textual and historical approaches.

The Terms “Hindu,” “Hinduism,” and “Hindu Traditions”

The term “Hindu” (derived from the Persian word sindhu) was first used by “outsiders” (i.e., Persians and others) as a designation for those people who lived east of the Indus River. “Hindu” and “Hinduism” became terms used for a religious identity and “system” (an “ism”) by British colonists in the 19th century to distinguish in their census materials those Indians who were not Christian or Muslim. Nevertheless, even if the terms were initially developed by “outsiders,” they have become indigenous terms – used by Hindus in both India and the diaspora – that have come to identify traditions that share certain elements of a worldview, narrative repertoire, and ritual grammar. However, although contemporary Hindus may self-identify as Hindus on various government forms, school registrations,2 and so on, when speaking among themselves, the term “Hindu” is much less commonly used than regional, sectarian, or caste identifications.

The parameters of Hindu traditions (a term I prefer over “Hinduism” in order to reflect the plurality of traditions) and the identifying features that “make someone a Hindu,” are difficult to identify given the hundreds of sacred oral and written texts, the wide diversity of ritual practices, and the absence of a singular religious authority or class of authorities. Simply being born into a Hindu family is one means of identification, without requiring or implying any level of ritual practice or theology. On the other hand, we have an example of a Hindu man who asked an Orthodox Jewish anthropologist whether he was Hindu, further asking if he cracked coconuts when he worshipped god. When the anthropologist answered that he did not, the man determined the anthropologist was not a Hindu; for this man, ritual practice determined Hindu identity (Hiltebeitel 1991, 28).

Dharma: A Way of Life and Religious Tradition

The Indian language term most frequently used to translate “religion,” dharma, implies correct action, practice, and ethics rather than a requisite set of beliefs (although it does not preclude beliefs). The term comes from the Sanskrit root dhr, which means to hold together, to support, or to order. Dharma can be interpreted, then, as that which holds the world together: ethics, ways of living, a “moral coherence” (Marriot 2004, 358); I use the term analytically to identify narratives and practices that help to structure or shape everyday Hindu lives.

I often ask my students in Hinduism classes how many have heard the now-common mantra, “Hinduism is not a religion, it’s a way of life.” Many Indian-American and non-Indian American students alike raise their hands. Then I ask, “How many of you have heard this saying in an Indian language?” No hands are raised. Most Hindus who speak this mantra have exposure to other religious traditions, such as Protestant Christianity, that tend to focus on belief and textual and institutional authorities, rather than everyday practices, as being inherent to the religion. They have internalized this emphasis in their own definition of “religion” in English and know that Hinduism does not fit very well, and therefore exclude their own traditions from “religion.”

The emphasis on texts and belief reflects a post-Enlightenment definition of what “counts” as religion. Religious studies scholar Vasudha Narayanan relates an interaction she had with one of her doctoral colleagues at Harvard University shortly after she had arrived in the United States in the 1970s; the student had given her several books to read on Hinduism and wanted to know what she thought of them. Her response, she writes, was,

Food … my grandmother always made the right kind of lentils for our festivals. The auspicious kind. We make certain vegetables and lentils for happy and celebratory holy days and others for the inauspicious ceremonies like ancestral rites and death rituals. And none of the books mentioned auspicious and inauspicious times

(Narayanan 2000, 761).

Given the centrality of everyday practices in Hindu traditions, over both time and space – including the foods one cooks at particular ritual occasions – I would prefer to expand the boundaries of what counts as “religion” to include “ways of life” rather than to exclude Hinduism. This inclusion may cause us to see practices in other religious traditions, such as cooking, in a new light – as religious practices. Some ritual traditions that are practiced by Hindus are also shared with Indian Muslim, Buddhist, and Christian communities (including rituals that divert the evil eye, some healing practices, and menstrual segregation); however, when a Hindu engages these practices, she/he frames them as something “we” (Hindus) do, or as dharma (appropriate conduct) as received from one’s family, and so I include some of these shared practices in this book.

So how does a Hindu learn his/her dharma, given that there is no singular book, creed, or religious authority in Hindu traditions (compared, for example, to the Tanakh, Bible, and Quran for Jews, Christians, and Muslims – although these traditions, too, rely in many contexts on non-textual means of knowing or learning their traditions). While there is a class of brahminic Sanskrit texts called the Dharmashastras (ca. 500 bce–400 CE), which provide intricate context-specific codes of social and ritual conduct, most Hindus do not learn their appropriate dharma from reading or hearing these texts, and many may not even know about or ever make reference to them. The primary way a Hindu learns his/her dharma is through observing and participating in family traditions and customs (Hindi niyam; Sanskrit paddhati), traditions passed from guru to disciples (who themselves become gurus or teachers), listening to performances of Hindu narratives, and simply by living in a Hindu-majority culture in which Hindu gods, temples, narratives, and rituals are “all around,” and a child imbibes them almost through osmosis.

Leela Prasad, in her ethnography Poetics of Conduct (2007), analyzes the ways in which ethical (dharmic) practices are learned and known in the small South Indian town of Sringeri, which is the site of an important matha (monastery and site of brahminic learning and exposition, including of the Dharmashastras). Prasad is particularly interested in the ways in which the term shastra (authoritative tradition of ethical action, or dharma; teaching) is invoked in everyday conversations and narratives. Through analyses of conversational narration, she finds that there is wide scope for interpretation of shastra and its authority, going much beyond reference to the textual tradition of the Dharmashastras. She argues that “… narration itself is an ethical act …,” and that stories are an important means through which Hindus learn dharma, that is, how to live in the world (Prasad 2007, 6). Prasad concludes that “‘shastra’ in lived Hinduism is truly elastic in its creative engagement of tradition, text, practice, and moral authority … as a moral concept, shastra coexists with other concepts of the normative” (12–13).3 This book includes many of these coexisting ways in which Hindus learn and know dharmic ways of living.

Context and Multiplicity

Although there is an Indian language term for universal dharma – sanatana dharma...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.2.2015 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Lived Religions |

| Lived Religions | Lived Religions |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Hinduismus |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Religion / Theologie ► Judentum | |

| Schlagworte | Hinduism • Hinduismus • <p>Hinduism, Trimurti, dharma, theology, religious studies, religion, Puja, Bhakti, religious practice, Divalia, Ganesh, vrats, Hindu tradition, India, diaspora, ethnography, anthropology of religion, Hindu rituals, Hindu festivals</p> • Religion & Theology • Religion, Issues & Current Affairs • Religionsfragen u. aktuelle Probleme • Religion u. Theologie |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-52818-2 / 1118528182 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-52818-1 / 9781118528181 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich