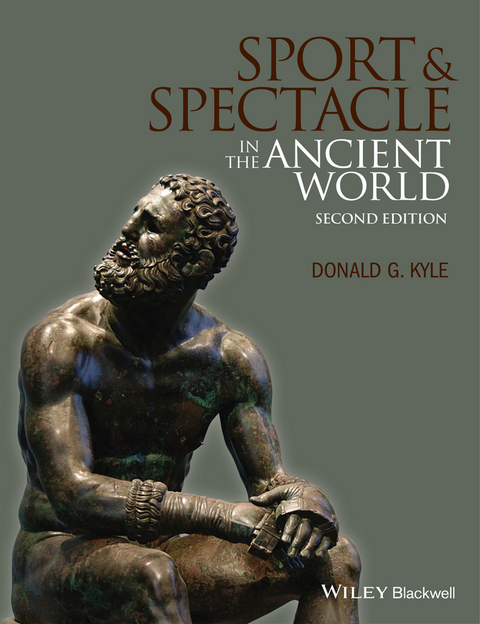

Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-61380-1 (ISBN)

The second edition of Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World updates Donald G. Kyle's award-winning introduction to this topic, covering the Ancient Near East up to the late Roman Empire.

• Challenges traditional scholarship on sport and spectacle in the Ancient World and debunks claims that there were no sports before the ancient Greeks

• Explores the cultural exchange of Greek sport and Roman spectacle and how each culture responded to the other's entertainment

• Features a new chapter on sport and spectacle during the Late Roman Empire, including Christian opposition to pagan games and the Roman response

• Covers topics including violence, professionalism in sport, class, gender and eroticism, and the relationship of spectacle to political structures

Donald G. Kyle is Professor, former Chair of History, and Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Texas at Arlington. He is the author of Athletics in Ancient Athens (1987), Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome (1998), Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World (Wiley-Blackwell 2007); and co-editor (with Paul Christesen) of A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity (Wiley-Blackwell 2014).

Donald G. Kyle is Professor, former Chair of History, and Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Texas at Arlington. He is the author of Athletics in Ancient Athens (1987), Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome (1998), Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World (Wiley-Blackwell 2007); and co-editor (with Paul Christesen) of A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity (Wiley-Blackwell 2014).

"This is without a doubt the single best overview of

ancient sport. Donald Kyle delivers a clear, lively, and detailed

account that reflects his unmatched erudition and insight."-

Paul Christesen, Department of Classics, Dartmouth

College

"Kyle furnishes a sophisticated and lucid account of sport and

spectacle as important cultural phenomena in antiquity.

Especially insightful is his treatment of both Greek and Roman

sport as spectacle. Most welcome too are the relevant

parallels and significant differences he observes between ancient

and modern athletics." - Hugh Lee, Emeritus Professor of

Classics, University of Maryland, College Park

"An excellent, wide-ranging survey of ancient sport. No

other introductory volume combines the study of Greek and Roman

sport and spectacle so effectively. This second edition adds a

wealth of new material to the original version." - Jason

König, School of Classics, University of St Andrews

Introduction: AncientSport History

I learned early on that sports is a part of life, that it is human life in microcosm, and that the virtues and flaws of the society exist in sports even as they exist everywhere else. I have viewed it as part of my function to reveal this in the course of my pursuit of every avenue of the sports beat.

Howard Cosell, Cosell (1974) 415

However propagandistic, Leni Riefenstahl’s film Olympia (1938) about the 1936 Olympics was a triumph of cinematography and an inspiration for later sport documentaries and photography. With striking camera angles, iconic forms, and ageless symbols, the film turned athletic intensity into aesthetic delight. With scenes of misty mythological times, an athletic statue coming to life and hurling a discus, robust maidens dancing outdoors, and ancient ruins of Athens and Olympia, the film evokes ancient glory. A torch relay of handsome youths brings the talismanic fire of Classical Greece across miles and millennia to sanction the “Nazi” Olympics (see Figure I.1). Almost seamlessly, the film transports the viewer from the supposedly serene pure sport of Ancient Greece to the spectacle of the Berlin Olympics with its colossal stadium, masses of excited spectators, Roman symbols (e.g., eagles and military standards) of the Third Reich, and, of course, the emperor Hitler as the attentive patron, beaming as athletic envoys of nation after nation parade through and salute him.

Figure I.1 Torch relay runner in Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympiad (1938).

© akg-images/Interfoto/Friedrich.

Riefenstahl’s commissioned effort took manipulative myth making to new lengths; but, instead of recording a triumph of the fascist will, in spite of itself the spectacle immortalized Jesse Owens as an athletic hero. With its characteristic element of suspense, of unpredictability despite appearances and agendas, sport triumphed over despotism and racism. Through the beauty and brutality of various contests, and the human virtue of athletes of diverse lands, sportsmanship survived on the field of play. The crowd, and in time the world, cheered even as the tyrant and his cultural and propaganda ministers watched. All were amazed. Everyone knew that something extraordinary, something spectacular, was taking place.

The 1936 Olympics and Riefenstahl’s film were not the first or last combinations of sport and spectacle. When talented, determined, and charismatic athletes strive against each other, athletic competition becomes a spectacle. People want to watch, and performers want to be watched, to have others appreciate their efforts and hail their victories. Ancient spectacles similarly incorporated physical performances, many of them on a competitive basis with rules, officials, and prizes. It was the modern world that decided that the activities it differentiated as “sport” and “spectacle”—and the athletes and performers regarded as “sportsmen” and “professionals”—were incompatible, even as the competitions and competitors coalesced in ever-grander and more popular modern games at colleges and in the Modern Olympics.

With its heroes and hustlers, its victors and victims, sport—the playing, organizing, and watching of sports—was, is, and will remain undeniably popular and significant. Ancient and modern civilizations share an obsession with physical contests and public performances, but just what are “sport” and “spectacle,” and how can they be studied and understood historically? How and why did sports and spectacles become so central, so moving, in the life of ancient Mediterranean civilizations? This work examines the prominence, forms, and functions of sports and spectacles in ancient societies, but first let me explain how the game should be played.

This is a study of ancient sport, not ancient sports, a sport history or a history of sport rather than a sports history or a history of sports. Traditional sports history tends to be event oriented, concentrating on individual sports and providing chronological narratives by leagues, teams, or players. Treating data (e.g., records and statistics) as facts, it favors anecdote above analysis. Instead, sport history pursues the phenomenon of sport over time, identifying and trying to explain its changes and continuity both causally and in context. It approaches ancient sport and spectacle not as isolated pastimes but as essential elements in social, civic, and religious life. Serious interdisciplinary sport history uses sport as a lens to examine human nature, societies, and cultures, not as an end in itself. Ancient sport historians have moved the field from antiquarianism to contextualization, from collection to collation, from enumeration to interpretation.1 In recent decades, we have improved our understanding of ancient sport by questioning traditional assumptions, integrating new archaeological evidence, reexamining existing texts and artifacts, and applying anthropological, comparative, and social historical approaches.

Most historians of sport agree that sport, in some form, is a universal human phenomenon, that agonism (competitiveness, rivalry, and aggressiveness) is fundamental to human nature, and that agonistic motifs abound in widely dispersed myths and literature.2 Most also agree that sport exhibits significant adaptations and variations over time and space. The impulse to sport emerged early and remains rooted in human instincts and psychology, but different human groups, classes, cultures, societies, and civilizations practice and view sport in revealing and characteristic ways. Sport cannot be studied in isolation from its historical, social, and cultural context, and sport historians now speak of cultural constructions, tensions, negotiations, and discourse in sport and spectacle.

Ancient sport is a growing and exciting field in which scholarly advances and controversies abound. Disillusioned by excessive athleticism and the impact of ideologies on modern sport, demythologizing scholarship has shown that modern movements have abused the ancient games for their own ends, turning them into what they wished the games had been. Traditional studies now seem methodologically antiquarian or ideologically burdened with assumptions about amateurism, athleticism, classicism, idealism, Hellenism, Eurocentrism, and Olympism. As modern sport and the Modern Olympics evolve, scholars have reexamined traditional and supposedly ancient notions of sport for its own sake alone. A traditional rise and fall paradigm of pristine origins, golden age, and later decadence has been challenged. Now more ideologically self-conscious, we realize that the study of cultural adaptation over time involves continuity as well as change in the phenomenon and in modern interpretations.

Using interdisciplinary approaches from comparative, political, and symbolic anthropology, ethnology, sociology, New Historicism, and cultural and social history (e.g., on rituals, performance, initiation, hunting, processions, identity, and more),3 scholars have gone beyond the traditional concentrations—the Greek Olympics and the Roman Colosseum—to look at the sporting activities and spectacles of earlier Near Eastern peoples, the archaeology of the Bronze Age Mediterranean, the crucial transitional Hellenistic era, local games with their intriguing contests, rites of passage, and issues of class and gender, the emergence of Etruscan and Roman spectacles, the facilities and stagecraft of spectacles, and the persistence of Greek sport in the Roman Empire. Research on ancient sport and spectacle in the last generation has been so fertile, innovative, and international that there is a need for a synthetic and suggestive survey to attract and assist students and scholars who have not studied antiquity from this perspective.4

This survey of demythologizing therapeutic trends in ancient sport studies challenges old moralistic conventions including the claim that there was no sport before the Greeks and the simplistic contrasting of Greek sport and Roman spectacles as polar opposites. After downplaying or ignoring cultures before the Greeks, traditional studies applaud Greek sport as admirable, pure, participatory, amateur, graceful, beautiful, noble, and inspirational, and they denounce Roman spectacles as decadent, vulgar, spectatory, professional, brutal, inhumane, and debasing. Taking a broader approach, this work argues that sport and spectacle were not mutually exclusive but rather compatible and complementary. Especially at advanced levels, in ancient as in modern times, sport and spectacle have very much in common.

Why Sport History?

Sport is eminently worthy of study because it is both relevant and revealing. If historians want to understand fully the societies they study, it is imperative that we study people intently engaged in work, war, or play. Why does it seem so important that we win—or above all not lose—games? As if we were on a primordial hunt or a battleground, sport means something much more than just the activity itself. Also, the sports that groups embrace are not a matter of serendipity. Local versions of sport are adapted (or constructed) in interaction with cultural norms and tastes. Both sport and spectacle are central to the social life of groups and the operation of states.

From schoolchildren to weekend quarterbacks, from doctors to lawyers, from entrepreneurs to politicians, from the YMCA to the World Cup, sport...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.11.2014 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Ancient Cultures |

| Ancient Cultures | Ancient Cultures |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Vor- und Frühgeschichte |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Altertum / Antike | |

| Schlagworte | Ancient & Classical History • Ancient Culture • Ancient world, ancient games, gladiators, chariot races, ancient sports, ancient spectacles, Greek Olympics, Greek games, Greek stadium, Olympic games, Roman Colosseum, Roman spectacles • Antike • Antike u. klassische Geschichte • Archäologie • archaeology • Archäologie • Classical Studies • Humanistische Studien • Klassisches Altertum • lifestyle • lifestyles • Sport • Sports |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-61380-5 / 1118613805 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-61380-1 / 9781118613801 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich