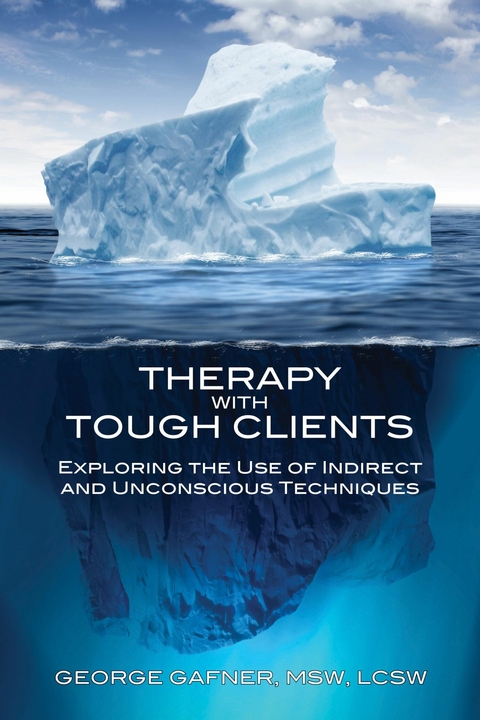

Therapy with Tough Clients (eBook)

316 Seiten

Crown House Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-84590-883-6 (ISBN)

George Gafner, MSW, LCSW, is director of the hypnosis training program and director of the family therapy training program at the Southern Arizona Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Tucson. He is the author of four previous books on hypnosis and hypnotic inductions.

Whether you're fairly new to therapy or you've practiced for many years, no doubt at times you've found yourself stumped with certain clients who leave you feeling perplexed and discouraged with that 'I-just-don't-know-what-to-do-next' feeling. George Gafner has been there and that's precisely why he wrote this book. The reality is that today's cookie-cutter treatment mentality presupposes that all people with, say, depression, can be treated essentially the same way, which virtually ignores the established fact that a good deal of a person's mental functioning is governed not by conscious choice but instead by automatic, or unconscious, forces that lie outside voluntary control

An enduring teachable moment

When we do unconsciously-directed work with clients we are privileged, as they open for us that window to the deepest part of them. When we direct therapy through that window—with story, anecdote, hypnotic language, pacing of ongoing response, or various other techniques—I call this an enduring teachable moment, as it is a time of heightened receptivity. But this is not a one-way glass like we used in the 1970s to view trainees doing therapy. We, as therapists, also have an ongoing process, much of it unconscious, reflected back through that window, and in this book I try to capture both sides of that window as I take you through therapy with two engaging and multidimensional people, Maggie and Charles. They represent two of the most complicated and challenging clients I ever had, and by working with them I demonstrate a host of techniques that you may find useful in doing therapy with your toughest clients.

Once I heard someone say that a delight in poetry is “discovering something I didn’t know I knew.” Now, recalling that discovery is an example of this enduring teachable moment, and I’d bet that whatever that person read that day in a poem continues to sit there deep within, waiting to be triggered in the future by a like association. So, too, an enduring teachable moment is evident when I run into a client I saw 15 years ago and she mentions, “You know, that old woman in the woods you told me about, I still think about her.” Something triggers the memory of the woman in the story. It may be mention of a cold day, a forest, or of some other aspect of The Three Lessons story she heard from me years ago, all inextricably linked to the meta-message of the story, that people have resources within to help themselves with their problems. That memorable tale, which I adapted from a story of the same name by Lee Wallas (1985), is an example of what you can do in your practice, borrowing from a story or technique in this book, adapting it to your needs, and fashioning it for whatever clinical scenario you encounter.

Luis, back from Afghanistan

As the unconscious is certainly the aegis of hypnosis, and as this book deals in part with hypnosis, let me share a clinical example that opened up this window to me as much as the client. Around 2005, I was referred a young Hispanic soldier, Luis, who had recently returned from Afghanistan. His problem was erectile dysfunction. He was in perfect health, on no medications, did not have depression or PTSD—despite months of harrowing combat—and like many hypnosis referrals, it came out of frustration after all else had been considered. Luis was married, of average intelligence, spoke good English, and said he didn’t drink or use drugs. He was calm, in no distress whatsoever, and said he wasn’t bothered at all about the war. His only concern was that he was impotent.

The next session we began hypnosis. He responded with deep trance and amnesia to a conversational induction and The Three Lessons story, which embeds the suggestion that people have resources within to help with their problem. The next session I employed a similar procedure but added an ego-strengthening story and set up finger signals for unconscious questioning. Using age regression, I asked him to go back in time to “any time in the past that might have to do with the problem … and when you’re there, Luis, you may let your ‘yes’ finger rise.” After about a minute his index finger twitched and he began to mutter some words that were unintelligible to me, but I did glean a fragment of a phrase, “I-U-D, I-E-D.”

I re-alerted him and discussed today’s session. It soon was apparent that his unconscious mind had mixed up the improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in the war with his wife’s new intrauterine device (IUD), and impotence resulted. Discussion normalized and integrated this phenomenon, the problem immediately resolved, he was seen one more time in a month and was doing fine, end of story. Now, how many sessions of talk therapy might have been needed to resolve that problem?

Peter in jail

Therapy with Luis was during a scheduled appointment in a comfortable office at the Veterans Affairs (V.A.) Medical Center. The conditions were optimal. But such conditions aren’t always necessary to elicit a similar response within unconsciously-directed therapy. For example, I am now retired, for the most part, but I used to work about four days a month at the local jail. The other day one of the psychiatrists grabbed me as I was walking by and asked me if I would see this very anxious client I’ll call Peter, a Black male being treated for bipolar disorder. I sat with Peter for a few minutes in a busy hallway outside the exam rooms in the medical section of the jail. The first thing I noticed was Peter’s very fast and shallow breathing.

I showed him deep breathing and asked him if I could tell him a little story while he practiced this better way to breathe. “You can close your eyes or keep them open, whatever you wish,” I told him He chose to close his eyes and I told him The Three Lessons story, which I often use early on. People continued to walk by in handcuffs and chains, doctors and nurses were talking, and it was business as usual while Peter responded highly favorably to the story. In two minutes we were done, his anxiety was allayed, and he left with some tools to help him in the future. I have had similar responses in even worse conditions there, like talking to them through the food trap in the door in segregation, or standing in the corner of a busy day room with the curious walking by, straining to hear what was being said. In other words, a nice office with a recliner and wind chimes music is nice, but if you don’t have it, you can improvise, even in the midst of rapists and murderers.

Standing on broad shoulders

In my years in this business I have learned from many, from my family, colleagues, people in the field, and my trainees, who came from divergent backgrounds and theoretical perspectives. However, my clients probably taught me more than anyone. For 38 years I worked at clinics and hospitals, and for 28 of those years I directed a program in family therapy and hypnosis training in the V.A. in Tucson, Arizona.

I learned from people who had extraordinary experiences, like the men who had been prisoners of war in World Wars I and II, as well as in later wars in Korea and Vietnam. I learned from the reactant and hostile, like the spouses and children who involuntarily attended family therapy, or those who were directed to attend one of the two anger management groups I conducted for 20 years. One Vietnam veteran with florid PTSD said he was eager to attend because “this is my 12th marriage and I intend to keep it.” He did well in the group and his wife was eternally grateful. Years after the group, when I encountered that man or many others, I asked them what they remembered about the group, and invariably they answered, “To take a deep breath or a time-out … but what I liked best was the stories you told.” Indeed, stories and anecdotes, both indirect, or unconsciously-directed techniques, have been my allies for many years.

I learned from my long-term therapy clients and I learned from the ones I saw only once or twice, like the paranoid personality disorder who defied me to try and help him. The V.A. is a fascinating place to work because you encounter a wide diversity of people with every kind of clinical problem. The youngest veteran I saw was 19 and the oldest 102. The oldest couple I saw had been married 76 years. Their recipe for a successful marriage? “Always talk things out and never go to bed angry.” I learned from the elderly schizoid woman whose eyes I never saw because of her mirrored sunglasses. I learned from the overly compliant and passive, the therapy addicts who lived in their heads and were resistant to all change however small. I learned from the 200 trainees I had over the years in psychology, psychiatry, nursing, social work and other disciplines. I estimate that over the years I had to do with some 10,000 clients that I either saw directly or whose cases I supervised. In this business we quickly learn that some we help, some we don’t, and some we never know because they just fade away.

Trying new things as we counter resistance

For years on Tuesday evenings I was a volunteer therapist at the refugee clinic of the University of Arizona where I saw victims of torture. These people from Central America, Africa and the Balkans had experienced all manner of cruelty, loss and humiliation. I’ve always done therapy in either English or Spanish, but sometimes at this clinic an interpreter was employed, usually a French-speaking medical student who had done a rotation in Africa. From those in the refugee clinic I learned how fleeting and precious life is, and how we need to make the most of those few minutes or hours we are with any client. Seeing people who were able to overcome the most awful circumstances somehow made it easier for me to help the majority of my clients, people whose problems were understandably dear to them but which paled in comparison to those of survivors of the Bataan Death March, or the lone survivor in a village where all were killed.

Along the way I learned patience. With patience you don’t give up on clients and you keep trying new things in order to make an impact. As we try new approaches and techniques we discover what may work in certain situations, but we...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.4.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie ► Allgemeine Psychologie |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Gesundheitsfachberufe | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Psychiatrie / Psychotherapie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84590-883-X / 184590883X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84590-883-6 / 9781845908836 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich