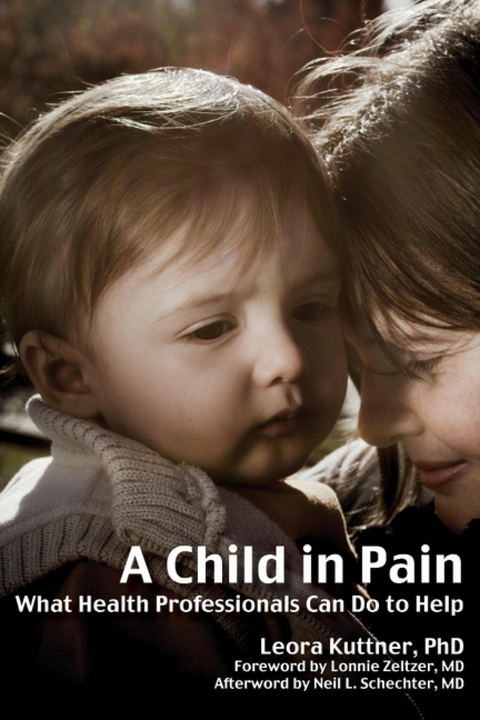

A Child in Pain (eBook)

416 Seiten

Crown House Publishing (Verlag)

9781845904555 (ISBN)

Leora Kuttner, PhD is a pediatric clinical psychologist who specializes in children's pain management. She is a Clinical Professor in the Pediatric Department of the University of British Columbia and BC Children's Hospital, Vancouver, Canada. Dr. Kuttner has authored A Child in Pain: How to Help, What to Do, a book for parents, and has also co-produced and directed award winning film documentaries on pediatric pain management, No Fears, No Tears, No Fears, No Tears - 13 Years Later, and When Every Moment Counts.

Chapter 1

Pain in Children’s Lives

“Pain is when it hurts.”

5-year-old boy

As children and teens grow and explore the world, they experience many falls, illnesses, and hurts of one kind or another. They turn to their parents to find relief from pain. Too often parents feel anxiety and fear, not knowing what to do in the face of their children’s pain, and turn to pediatric professionals for the expertise and guidance to provide their child with sufficient relief. Pediatric health professionals at all levels of care need to know how to provide this necessary help.

Fortunately today many breakthroughs in scientific research have increased our understanding and treatment of childhood pain. The goal of this book is to make this information easily accessible to those working directly with children. With a knowledge of the most effective therapies and treatment combinations in conventional and complementary medicine, professionals can help children and their parents to better manage minor and major pain from injuries and illness. Instead of minimizing, misunderstanding, or dismissing a child’s pain, a skilled professional can provide prompt pain relief and empower the child to cope. This requires a combination of helping the child to understand and interpret the pain sensations and to develop coping skills, as well as being aware of the treatment options to ease the pain.

Pain is part of growing up. Young children frequently fall and scrape themselves as they learn to walk, run, climb, and ride a bicycle. This is a time of developing co-ordination and skill and, as a consequence, learning about pain and suffering. Research has shown that preschool children during play, experience an average of one ‘owie’ or ‘boo-boo’ every three hours (Fearon, McGrath, & Achat, 1996). Children encounter accidents at home, in parks, in cars, and on the playground at school. They may experience pain when they get a tooth filled at the dentist’s office or when they have an injection at the doctor’s office. Some children and adolescents struggle for years with painful diseases and hospital treatments.

This chapter discusses the role that pain plays in the human body, the relationship between pain and the brain, and types of pain. A few widely held attitudes or misconceptions about pain have prevented parents and health care providers from dealing promptly and appropriately with children’s pain. At the end of this chapter I review and debunk misconceptions about pain.

The Protective Value of Pain

Pain is protective. It provides vital information to guide us in the use of our body, informs us about its condition, and helps us survive and remain intact. As health care professionals, part of our responsibility towards children is teaching them to respect pain signals and to learn how to interpret and cope with them. We know from interview studies on children’s concepts of pain that they seldom mention any beneficial aspects of pain, such as pain’s diagnostic value, its warning function, or its role in determining whether treatment is effective (Abu-Saad, 1984a,b,c; Ross & Ross, 1984a,b; Savedra, Gibbons, Tesler, Ward, & Wegner 1982). Children need to know that pain is their personal safety-alarm system, interpreted by the brain in a highly rapid and sophisticated way. Pain messages quickly tell us if there is something wrong with our organs, muscles, bones, ligaments, and tissues, all of which are interwoven with nerve fibers and pain mediators that rapidly carry pain messages to, from, and within our brain. Children need to be informed that part of the sophistication of pain is that memory, emotions, previous learning, beliefs, stress, endocrine and immunological processes, as well as the current meaning of pain, all factor into how the pain message is experienced.

In its healthiest form, short-term acute pain is protective, alerting and preventing damage to one’s body. As David, aged four and a half, discovered: “You’ve got to listen to your stomach when it’s hurting, ’cause if you don’t, your stomach will get upset!” David knew this firsthand; for five days he had had stomach pains and gastric spasms and had been throwing up. The pain signals had taught him that if he continued eating the tuna sandwich his well-intentioned mother had given him, his stomach might send it back again. Recovering from a gastrointestinal virus, David had come to respect the signals he was receiving from his stomach: to eat only what his stomach could handle and when to stop. Because his actions helped settle his pain and nausea, and because he was being listened to – although he was only four and a half – he learned to manage his own recovery, and set the stage for dealing effectively with the experience of pain in the future.

Children learn about their bodies when we encourage and teach them to pay attention to their body’s messages and sensations. They learn to interpret the different pain signals and determine what gives the best form of relief. This learning is refined over a lifetime. Even very young children can be taught to share their pain sensations so that we can determine what is going on, their severity, and what will be most effective in helping the pain to go and stay away.

The value of pain is poignantly evident when we encounter children born with one of the rare conditions of insensitivity or indifference to pain (Nagasako, Oaklander, & Dworkin, 2003). Throughout their lives, these children are at great risk of damaging their bodies, particularly their eyes, hands, fingers, joints, and feet. Pain is disabled by their genetic condition and does not protect them. It does not alert them to stop an action that will cause injury, or prompt them to call for help when they experience the early pain signals of a medical crisis such as appendicitis. These children continue to walk on sprained ankles and damage the tips of their fingers and their legs; frequently they require artificial protection such as braces and guards. By school age, these children have already sustained significant and often irreparable damage to their limbs.

Pain in the Body and the Brain

David Morris (1991), a Professor of Bioethics, writes about the outdated belief that pain can be divided into physical and mental pain. He calls this ‘the Myth of Two Pains.’ According to this myth, there are two entirely separate types of pain: physical and mental. Morris elaborates: “You feel physical pain if your arm breaks, and you feel mental pain if your heart breaks. Between these two different events we seem to imagine a gulf so wide and deep that it might as well be filled by a sea that is impossible to navigate.” (p. 9)

This concept, that pain is either in the body or the mind, goes back to the 17th-century philosophy of René Descartes, who argued that the body and mind were separate. He also maintained that there was a one-to-one relationship between the injury and the amount of pain felt – a theory now debunked. Today’s scientific evidence is that there is continual interaction in the nervous system between our physical and mental functions such that any division between them is an artificial construct.

One of the earliest medical practitioners to publicly question this mind-body split was Dr. H. Beecher, a Boston surgeon who traveled to Europe with U.S. troops during World War II. In 1956 he published a paper which described how soldiers who had very similar wounds to the civilians he had treated at home, required significantly less pain medication (Beecher, 1956). In talking with these men, he realized that the meaning of their pain was very different from that for civilians. Pain to these soldiers meant they were alive and were out of active warfare. War wounds were a ticket home. Beecher’s reports challenged the thinking of the day and importantly showed that the amount of tissue damage often bore little correspondence to the level of felt pain, and there was no validity in a mind-body dichotomy These conclusions are now widely accepted in clinical practice. We now know that the meaning of a person’s pain is subjective, highly personal, and variable from one situation to another, and that this meaning will influence how the pain is experienced. Mental pain can be physically experienced and physical pain mentally experienced. Mind and body are integrated systems.

Definition of Pain

That pain is subjective in no way detracts from the validity of the physical origins of the pain. Pain signals travel through the limbic system, the part of the brain most involved in emotion and motivation (see Chapter 2). When in pain, we are affected emotionally and our feelings can range from distressed, anxious, vulnerable, weepy, to depressed. These emotional or affective correlates are well documented in the literature. The official definition of pain by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) acknowledges this: “Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage. Pain is always subjective. Each individual learns the application of the word through experiences related to injury in early life.” (1979, p. 249)

Pain is experienced as emotional and mental suffering, as well as a distressing physical sensation. Above all it is subjectively experienced and so is private and entirely personal. Consider the instructive words of sixteen-year-old Jodi, who coped for five years with severe pain from Guillain-Barré, a neuromuscular syndrome:

Pain is something that no one can...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.8.2010 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Pädiatrie | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Psychiatrie / Psychotherapie | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Schmerztherapie | |

| ISBN-13 | 9781845904555 / 9781845904555 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich