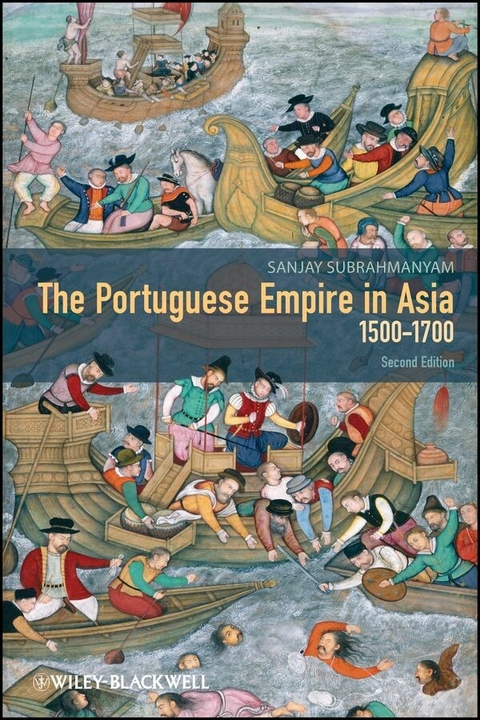

The Portuguese Empire in Asia, 1500-1700 (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

9781118274026 (ISBN)

- Features an argument-driven history with a clear chronological structure

- Considers the latest developments in English, French, and Portuguese historiography

- Offers a balanced view in a divisive area of historical study

- Includes updated Glossary and Guide to Further Reading

Sanjay Subrahmanyam is Professor and Chair of Indian History at UCLA, and has earlier taught in Delhi, Paris, and Oxford. His publications include The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama (1997) and Three Ways to be Alien (2011).

Featuring updates and revisions that reflect recent historiography, this new edition of The Portuguese Empire in Asia 1500-1700 presents a comprehensive overview of Portuguese imperial history that considers Asian and European perspectives. Features an argument-driven history with a clear chronological structure Considers the latest developments in English, French, and Portuguese historiography Offers a balanced view in a divisive area of historical study Includes updated Glossary and Guide to Further Reading

Sanjay Subrahmanyam is Professor and Chair of Indian History at UCLA, and has earlier taught in Delhi, Paris, and Oxford. His publications include The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama (1997) and Three Ways to be Alien (2011).

Abbreviations x

Maps xi

Tables xii

Acknowledgments xiv

Preface to the Second Edition xv

Preface to the First Edition xvii

Introduction: The Mythical Faces of Portuguese Asia 1

1 Early Modern Asia: Geopolitics and Economic Change

11

Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-century States 13

The Circulation of Elites 22

Towards a Taxonomy 27

Long-term Trends 30

2 Portuguese State and Society, 1200-1500 33

Crown and Nobility 33

In Search of a Bourgeoisie 40

Mercantilism and Messianism 48

Summing Up 55

3 Two Patterns and Their Logic: Creating an Empire,

1498-1540 59

The Early Expeditions 60

From Almeida to Albuquerque: Defining the First Pattern 67

The Second Pattern: East of Cape Comorin 74

The Logic at Work: Portuguese Asia, 1525-40 78

Towards the "Crisis" 83

Notes 85

4 The Mid-Sixteenth-century "Crisis" 87

The Dilemmas of Joanine Policy 88

S´as, Sousas, and Castros: Portuguese Asian Officialdom in

the Crisis 96

The Mid-century Debate 104

The Far Eastern Solution 107

The Estado in 1570 113

Notes 114

5 Between Land-bound and Sea-borne: Reorientations,

1570-1610 115

Trade and Conquest: The Spanish View 116

Spain, Portugal, and the Atlantic Turning 120

Girdling the Globe 124

The "Land" Question 130

The Maritime Challenge 141

Concessions and Captains-Major 145

The Beginnings of Decline? 150

6 Empire in Retreat, 1610-1665 153

Political Reconsolidation in Asia, 1570-1610 154

Syriam and Hurmuz: The Beginnings of Retreat 160

Reform and Its Consequences 167

The Decade of Disasters: Portuguese Asia in the 1630s 172

Restoration, Truce, and Failure, 1640-52 181

The Retreat Completed, 1652-65 186

Asians, Europeans, and the Retreat 188

Notes 189

7 Niches and Networks: Staying On, 1665-1700 191

The Cape Route and the Bahia Trade 192

The Vicissitudes of the Estado: The View from Goa 198

Mozambique, Munhumutapa, and Prazo Creation 206

The Portuguese of the Bay of Bengal 211

Survival in the Far East: Macau and Timor 217

The Portuguese, Dutch, and English: A Comparison 222

8 Portuguese Asian Society I: The Official Realm 227

The Problem of Numbers 228

The World of the Casado 236

Networks, Fortunes, and Patronage 243

"Portuguese" and "Foreigner" 250

Rise of the Solteiro 253

The Impact on Portugal 257

9 Portuguese Asian Society II: The Frontier and Beyond

261

Renegades and Rebels 262

Mercenaries, Firearms, and Fifth Columnists 269

Converts and Client Communities 274

A Luso-Asian Diaspora? 279

10 Conclusion: Between Banditry and Capitalism 285

Glossary 295

A Note on Quantitative Data 303

Bibliography 307

Maps 323

Index 333

"This masterful history of Europe's first great Early Modern

maritime empire goes well beyond the limits of traditional

nationalistic and Eurocentric interpretations. Integrating European

and Asian sources, Subrahmanyam's new edition is a synthetic,

interpretative and at times speculative book that sets the

Portuguese Indian Ocean empire in the context of Asian and World

history. There is no book in English that provides a better

introduction to this topic." (Expofairs.com, 23

October 2013)

"This masterful history of Europe's first great Early Modern

maritime empire goes well beyond the limits of traditional

nationalistic and Eurocentric interpretations. Integrating European

and Asian sources, Subrahmanyam's new edition is a synthetic,

interpretative and at times speculative book that sets the

Portuguese Indian Ocean empire in the context of Asian and World

history. There is no book in English that provides a better

introduction to this topic."

--Stuart B. Schwartz, Yale University

"Sanjay Subrahmanyam's classic study of the Portuguese Empire in

Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries has stood the test

of time. Rich in penetrating insights and firmly anchored in both

an intimate knowledge of the Portuguese sources and a profound

understanding of the Asian contexts, it describes and explains,

with masterful clarity, a subject that was for long obscured by

ignorance, prejudice and misunderstandings. Now, this second

edition - with a new preface, thoroughly up-dated

bibliography and minor additions and corrections to the text

- will certainly be most warmly welcomed."

--A. R. Disney, La Trobe University

"Sanjay Subrahmanyam gives us a masterly overview of the early

modern Portuguese Empire in Asia. Written by one the leading

historians of our time, this is an illuminating study on the

complex interactions between Portugal and Asia in the sixteenth and

seventeenth centuries. Subrahmanyam truly redefines the field with

this work, which explains why the present book was able to overcome

the natural 'ageing effects' of a piece originally written two

decades ago."

--Jorge Flores, European University Institute,

Florence

1

Early Modern Asia

Geopolitics and Economic Change

The world between the Cape of Good Hope and Japan, where the Portuguese strove to build an elaborate network of trade and power between 1500 and 1700, was not a static one. It was characterized by change, at times almost imperceptible, at other times more clearly visible, both at the institutional and at the functional level. To understand Portuguese actions in Asia, therefore, and to comprehend the accommodations they had to make as well as the avenues they used, one needs to do more than describe the “Asian stage” on which they were actors. Rather, it is necessary to consider the problem of the dynamics of Asian history over these two hundred years.

The population of Asia in about 1650 was around 300 million, from a world population of perhaps 500 million. A hundred years later, in 1750, the continent still accounted for roughly 60 percent of the world's population, which had by then risen to around 700 million. Over the century and a half prior to 1650, when estimates are much harder to obtain, it is likely that there had already been a fair degree of expansion in numbers; after the mid-fifteenth century, all over Eurasia, the recovery from the Black Death takes decisive shape in the form of a demographic expansion. We would probably not be far wrong to place Asia's population in 1500 at between 200 and 225 million, which means that the Portuguese “saw” over the first two hundred years of their presence in Asia something like a doubling of the continent's population.

This population was, needless to say, unevenly distributed. It appears clear that tropical and semi-tropical Asia accounted for a far larger share of the total population than regions farther north, but this was a difference that was not quite so marked at the end of our period as at its beginning. At the farthest limit of the space we are concerned with was Japan, whose modern historians are agreed that the period between 1500 and 1700 witnessed a far more rapid growth of population than either the fourteenth or the eighteenth century, which respectively preceded and succeeded it. Indeed, if the estimates of scholars like Akira Hayami are acceptable, we may conclude that population growth rates in early modern Japan (which are said to have ranged between 0.8 and 1.3 percent per annum) were amongst the highest anywhere in Asia (Hall et al. 1981). In sharp contrast is Southeast Asia, whose historians suggest very slow population growth over the period 1600 to 1800; while this periodization does not permit us to speak directly of the sixteenth century, the impression is certainly left that rates of demographic change in that area (whose population may have been some 22 million in 1600) rarely exceeded 0.2 percent a year over the entire period from 1500 to 1800 (Reid 1988: 11–18).

Sandwiched between Japan and Southeast Asia, the two outliers in early modern Asian demographic history, lie other regions, some closer to Japan in their experience, others better approximating the Southeast Asian case. In the former category is China, whose population grew from about 60 million in 1400 to 180 million by 1750, even if a significant acceleration to this growth was given only after 1680 (at which point China's population has been estimated at a mere 120 million) (Banister 1987: 3–7). In the latter category, we must include much of South and West Asia, where one has to proceed on the basis of largely qualitative evidence, since population statistics are largely dubious until the eighteenth century. Taking one thing with another then, it is possible to assert that the balance of population in Asia gradually shifted from south and west to north and east over the period.

Not only did total population rise and its balance shift; the period also saw the consolidation of some great urban centers, and the decline of others. Cities like Delhi, Agra, Vijayanagara, Aceh, Kyoto, Isfahan, and Istanbul (the last lying in a sense between Europe and Asia), were comparable in order of magnitude and complexity of social structure to any of the European cities of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Nor was the change purely an urban phenomenon: partly under the pressure of population and partly for other reasons, land under cultivation expanded, as did manufacturing production, with India and China in the seventeenth century possibly accounting for over a half of the world's textile production. To reiterate our initial point, then, even the most obvious of indices do not support the idea of a static Asia that had to confront a dynamic and expanding Portugal.

Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-century States

The changes that took place in Asia over these centuries are most obvious and visible, however, at the level of elite politics. In the sixteenth century, two very substantial and powerful states – of the Mughals and the Safavids – were formed in southern and western Asia, while still another state, the Ottoman one – grew considerably in strength. In southern India, the great political system centered around the metropolis of Vijayanagara first consolidated itself and then, in the latter half of the century, entered into decline. Equally dramatic changes are to be observed in the careers of states of Southeast and East Asia: in the former case, Aceh, Arakan and to a lesser extent Makassar are three remarkable sixteenth-century success stories, while in the Far East, the turmoils of the sixteenth century eventually throw up a lasting institution in the bakufu – the “shadow” government of the warlord house of the Tokugawas in Japan, who ruled behind the façade of imperial sovereignty until as late as 1868.

And yet, these changes can quite easily be dismissed as of no real consequence, as indeed they have often been by adherents of the “Omar Khayyam approach,” who insist – like the author of the Rubaiyat in its English version – that early modern Asian state-formation is well encapsulated in this verse:

Think, in this batter'd Caravanserai

Whose Portals are alternate Night and Day,

How Sultan after Sultan with his Pomp,

Abode his destined Hour, and went his way.

(verse XVII)

That is to say that these changes represent no more than a replacement of one regime by another, all of which were much the same in essential character. This has, after all, for long been the central thrust of such theories as the “Asiatic Mode of Production,” or “Oriental Despotism,” which stressed the static and unchanging character of both Asian societies and the states that ruled over them. If it is indeed our contention that the states formed in Asia in this period (which we will call early modern) differed from those of an earlier epoch (extending from say the eighth to the fourteenth centuries, which we might term “medieval”), how did they do so?

Before we enter into this question, however, it may be useful to differentiate between types of states in early modern Asia. It has been usual to distinguish Asian states of the period under two broad heads: first, the massive, agrarian-based imperial formations, such as the Ottomans, the Safavids, Vijayanagara and the Mughals, the Ming, and Qing in China, and Mataram in Java; in contrast, the relatively small-scale (usually coastal) states like Kilwa, Hurmuz, Calicut, or Melaka, which are thought to have been essentially trade-based, thus drawing their resources not so much from the harnessing of force under prebendal systems as from the control of strategic “choke-points” along key trade routes. Let us consider the Ottomans as an example of the first type. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, their central fiscal institution is seen as the timar, a revenue-assignment given to timariot prebend-holders who rendered military and other services to the state. Despite the attempts to develop central institutions designed to reduce the dependence of the state on such dispersed forces – attempts that are located by historians in particular during the reign of Sultan Süleyman “the Magnificent” (r. 1520–66) – it is argued that the Ottomans could never throw off their character as a state whose fundamental institution was a combination of the classic Islamic iqta’ assignment, and a “feudal” land-grant deriving from the Paleologues, the last dynasty to rule Byzantium. The timar, like its counterpart the jagir in Mughal territories, is thus often seen as holding the key to an understanding of how the Ottomans functioned, and also why they failed to modernize and compete with the West (Shaw 1976).

It is implicit in most characterizations of states like the Ottoman and Mughal empires that the bulk of their revenues must have come from the “land,” rather than from “trade.” In practice, these categories prove rather difficult to disentangle in contemporary documents. Often, taxes on agricultural produce were collected through the control of trade in these goods; further, “land” was a convenient category for purposes of assignment, since it concealed the fact that what was in fact being parceled out was the right to use coercive force. Still, it is certainly true that if we were to examine the Ottoman budgets of the sixteenth century, the revenues of the greater part of the provinces under their control would show a preponderance of collections under categories other than “customs-duties.” Thus, the provincial budget...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.3.2012 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Wirtschaftsgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Asian & Australasian History • Asian History • Colonial • Early modern • Early Modern History (1500-1780) • Economic History • economic imperialism • Economics • European Empires • Geschichte • Geschichte / Asien u. Australasien • Geschichte der frühen Neuzeit (1500-1780) • Geschichte der frühen Neuzeit (1500-1780) • History • Indian Ocean • Portugal • Volkswirtschaftslehre • Wirtschaftsgeschichte |

| ISBN-13 | 9781118274026 / 9781118274026 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich