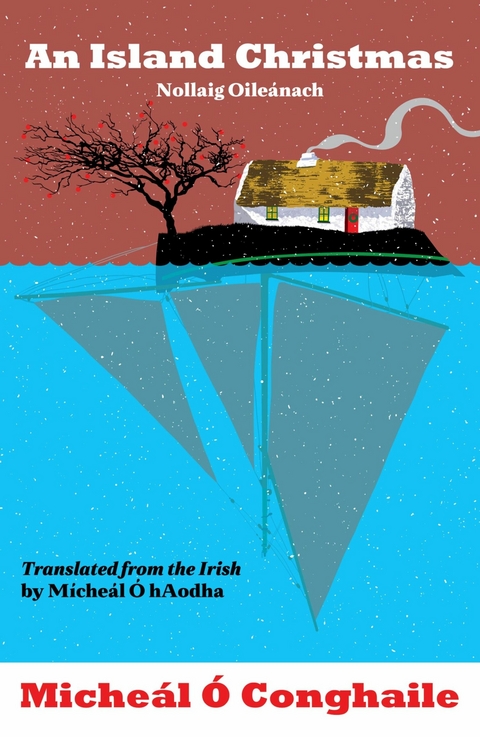

Island Christmas - Nollaig Oileanach (eBook)

120 Seiten

Mercier Press (Verlag)

978-1-78117-847-8 (ISBN)

Micheál Ó Conghaile, born in 1962 in Connemara, founded Cló Iar-Chonnacht in 1985. A respected writer, his accolades include The Butler Literary Award (1997) and the Hennessy Literary and Irish Writer of the Year Awards (1997). Elected to Aosdána in 1998, he was a writer in residence at Queen's University and the University of Ulster (1999-2002). Notable works include 'The Colours of Man' (2012) and 'Colourful Irish Phrases' (2018). He received an honorary degree from NUI Galway in 2013

In 'An Island Christmas - Nollaig Oileanach', celebrated Irish author Micheal O Conghaile takes readers on a heartfelt journey through his childhood memories of Christmas on the now-abandoned island of Connemara's Inis Treabhair.'An Island Christmas - Nollaig Oileanach' transcends the holiday season, weaving together tales of the simple joys of Christmas on the island with the broader tapestry of childhood memories, friendships, and the cherished personalities of the island community. O Conghaile reminisces about the unique traditions and customs of his island upbringing in the 1960s and 70s in this captivating memoir. Delving into the island's social history he paints a vivid picture of family life in an intimate portrait of island culture and a pre-electric era that will captivate readers of all ages.Though the island is no longer inhabited, O Conghaile's recollections serve as a poignant reminder of the enduring importance of family, community, and the magic of childhood. Whether you are a fan of O Conghaile's previous works or new to his writing, 'An Island Christmas - Nollaig Oileanach', offers a heartfelt and enchanting glimpse into a bygone era, making it a delightful read for any time of the year.An inspiring insight into the life of a passionate artist and powerhouse behind the resurgence of Irish language writing and publishing, witness O Conghaile's journey from an eager young boy tapping away on a typewriter to the founder of renowned publishing house Clo Iar-Chonnacht. Translated from the Irish by Micheal O hAodha.

Micheál Ó Conghaile, born in 1962 in Connemara, founded Cló Iar-Chonnacht in 1985. A respected writer, his accolades include The Butler Literary Award (1997) and the Hennessy Literary and Irish Writer of the Year Awards (1997). Elected to Aosdána in 1998, he was a writer in residence at Queen's University and the University of Ulster (1999-2002). Notable works include "The Colours of Man" (2012) and "Colourful Irish Phrases" (2018). He received an honorary degree from NUI Galway in 2013

As you’d expect, there were many preparations made for Christmas each year. The way I remember it however, we didn’t do a whole lot with the house as regards cleaning and painting. It was in summer time or when ‘the stations’ took place that people really did up their houses. The stations were held on the island twice a year and whatever house it was held in was scrubbed from top to bottom, or at least that part of the house the people of the island gathered. Each house held the stations one after another, a fact which meant that we had the stations in our house every three years or so. Whenever it came around, we cleaned the house from top to bottom and painted all the walls, doors and windows. There was no such thing as PVC windows back then, and it was a right torment painting the windows at the time. Between inside and outside the house, there were so many timbers and sides to each window that it was nearly impossible not to miss some small section of timber, despite your best efforts – some small section that made a fool of the rest of your work, once the mistake was noticed a day or two later. The exterior walls of the house were whitewashed every summer and this meant that they always had a nice bright, chalk-white sheen to them. The road outside was made neat also by applying sand or daub clay to it. There were a couple of daub holes on the island and you’d shovel it out and clear the stones, big and small from it with a pick, then bring the yellowish daub home in bags on the donkey’s back or in a hand-barrow or wheelbarrow after which you spread it out on the road. It smoothed out the surface of the road for a while anyway.

We cleaned the chimney every year, usually before Christmas. Sometimes we cleaned it ourselves but the neighbours often gave us a helping hand with it too, when we were very young. Sometimes during the year, people from outside the Gaeltacht would go from house to house on the island cleaning chimneys and the like. This was the time before ranges became more common and there was an open fire in most houses. Chimneys were often cleaned with a rough brush made from a cluster of bushes and branches bound tightly together. A big bundle of them tied with a rope which were then pulled up and down through the chimney. One person would be up next to the chimney-pot on top of the house and someone else down below at the hearth, and they pulled up and down against one another as hard as they could to clean out as much soot as possible. The soot often ended up all over the floor and the people below often took the brunt of it, especially whoever was closest to the hearth. But this did the job until the brushes with the long extensions became more common, brushes that were specially-made for the task.

As regards the major cleaning that we did every summer there was a lot of work involved with it. Every room in the house had to be done, one after another; all the bedclothes washed and hung out on the line to dry. Every nook and cranny in the house was cleaned from top to bottom and all the walls were painted; even the pictures on the walls had to be taken down and their frames painted. The picture-frames were painted bright-silver or gold usually. There were small special pots of paint available for this task in certain shops in Galway city. The legs and the frames of each table and chair were carefully washed, and the concrete floor of the kitchen was scoured and scrubbed clean as well.

One memory in particular that I have of the stations relates to the ‘priest’s sugar’. There were very few sweet things available other than sugar when I was a child and everyone, whether young or old, tended to add a couple of spoons of sugar into their mug of tea. They used regular sugar from the bag of course but once the stations came around, sugar cubes had to be got in especially for the priest’s breakfast, as we called it – the tea the priest drank after he’d said the station mass. This was why the sugar cubes were commonly referred to as ‘the priest’s sugar’. You couldn’t buy them in many shops in Connemara at the time, I think, so you had to go into Galway to get them so they were on the table the day of the stations. You had to show a great deal of respect to the priests back then, far too much really. Brown sugar was often provided also for the occasion in case the priest preferred this, even if this was another item that people didn’t often have themselves, at home.

We reared a pig every year that we slaughtered just before Christmas. My father butchered it – to be more exact. I’m sure that everyone has heard that phrase ‘muc i mála’ (‘pig in a bag’ or ‘pig in a blanket’) and once a year, in spring, my father would come home with a bag inside which something was squealing loudly. It was a banbh (piglet) that we’d feed up and fatten for the rest of the year until it’d grown into a fine, well-fed pig come Christmas-time. We fed the pig mainly on whatever food was left over. The slops of tea and milk left in the teapot or the mugs or crusts of bread with a few potatoes mixed in. Potato skins and cabbage cut into pieces and some meal when the pig was a bit older. A bucket-full every day or so. The bucket for the pig’s food was always left under the kitchen-table and known as the slop-bucket and any leftovers from meals were thrown into it over the course of the day. Whatever was in the bucket was brought to the shed and thrown into the pig’s trough every morning and afternoon. It goes without saying that the pig was always waiting eagerly for her daily feed. She alternated between being locked inside in the shed for long periods or being let out to wander the fields.

Once the pig got a bit older and stronger, they inserted one or two big rings through her snout to stop her from slamming her head against the door of the shed; the pig would get so strong after a while that there was a danger if she continued this, she’d break the door down trying to get out. The nose rings put a stop to this however. We had a special pincers to make the holes for the nose rings. Normally, it was a pair of nose rings that were put into her snout rather than a single ring and, of course, the poor pig would moan and squeal loudly while the piercing was being done. I suppose it must’ve been similar to someone getting pierced for a nose-ring or an earring without any anaesthetic or painkiller! That’s what I’d imagine anyway. It did the job however when it came to controlling the pig’s wildness or aggression. That said, I think that a certain injustice has been done to the pig over time in popular culture and she hasn’t been given her due as an animal really. ‘You dirty pig’ is a phrase that’s often used as an insult towards someone else. Or ‘He’s just a big pig’ or ‘he’s just a pig of a man’. And I don’t understand why this association of the pig with filth and dirt exists seeing as pigs are cleaner and far less-dirty than the majority of other animals.

For example, when you kept pigs in the shed, they’d never dirty the whole place at all like other animals but always went over to the same corner of the shed to do their business, a spot that was a good distance from where they slept. They sure did – as much as to say that this corner was their toilet – this is very different to the cow that dirties everywhere and anywhere in the shed. I don’t understand therefore where that English-language phrase – ‘As happy as a pig in shit’ – comes from originally. The only time that I ever saw pigs deliberately getting dirty was in summer when the weather was so hot that they needed shelter or shade from the strong sun – as it’s very easy for a pig to get sunburned because of its bright, white skin – unlike a calf, a donkey or a sheep! On days like that, you’d spot the pig going down into a drain or a ditch or wherever the ground was soft and rolling themselves in the mud and water to cool off. And she’d cover herself with a skin made of black mud to protect herself against the sunburn. Yes indeed – this was the factor fifteen or factor twenty the pig used on a very hot summer’s day! Necessity is the mother of invention as they say, and the pig is no fool, not by a long shot.

I hope you don’t mind now, if I give a short description of how they slaughtered the pig. Of course, I’ll make it short, concise and to the point because it wasn’t the most pleasant thing in the world. I don’t think that pigs are slaughtered in this way in Ireland anymore; it wouldn’t be allowed as it’d be considered too cruel; that said, I’m sure that pigs are still slaughtered in this manner nowadays in plenty of other countries, particularly in poorer countries and in more remote regions of the world.

I’ll begin now so. As mentioned earlier – in case I’ve wandered off the point a little bit – it was just before Christmas that we slaughtered the pig. My father did the job with some of the neighbours helping him. A few of us used to help him out too when we got a little bit older. They wouldn’t feed the pig for a day or two beforehand so that its stomach and intestines weren’t full and it was cleaned out in as far as possible; it was like somebody pre-paring for an operation, I suppose. This...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.10.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 16 pages |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Ethnologie ► Volkskunde | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | An Island Christmas • author memoir • books about familiies • books about irish life • books on islands • books to read aloud • christmas in bygone days • christmas traditions in ireland • colloquial • friendly • heartwarming stories • irish books • irish books best sellers • irish books non fiction • Irish customs • Irish islands • personal memoir from Ireland • starlit • the magic of Christmas • translated from Irish • works in translation |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78117-847-X / 178117847X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78117-847-8 / 9781781178478 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich