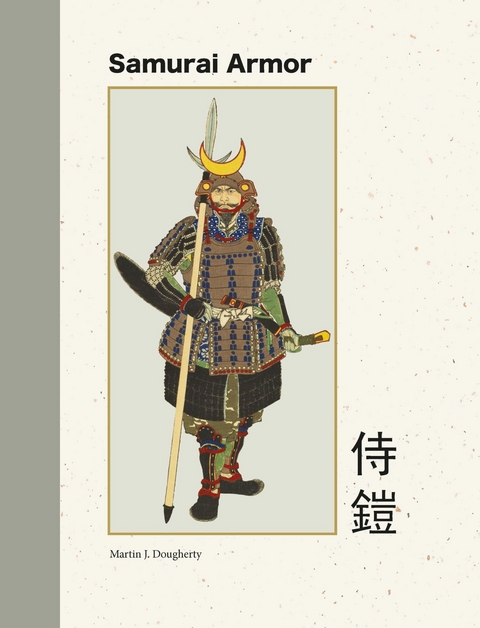

Samurai Armour (eBook)

224 Seiten

Amber Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-83886-711-9 (ISBN)

Japanese Samurai were apex warriors, superlative fighters dedicated to their daimyo, or lord, and living according to the principles of bushidō, an honour code that stressed selfless service, martial excellence, valour in battle and implacable determination. Often fighting on horseback and skilled archers, they developed a style of armour which, although changing over time, suited the dexterous combat techniques developed in Japan in the medieval and early modern eras.

Samurai Armour provides a vivid and informative guide to the many types of armour worn by Japanese warriors from the 10th to the 19th centuries. Learn about the classic o-Yoroi ('great armour'), designed for its lightness and flexibility for firing a bow from horseback; understand the development of the haramake ('belly wrap') armour, worn by the ashigaru men-at-arms - a new class of foot soldier that emerged during the Warring States period (1467-1615); explore the many types of classic Dō-maru, a heavy box-like armour constructed from flexible small scales of leather or metal laced into plates with cord; and see the various armoured elements used by samurai, including highly decorative kabutos (helmets), haidate (thigh guards) which were tied around the waist, and elaborate ornamental mempo (face masks) designed to reflect the personality of the wearer and strike fear into his enemies.

With 200 photographs and illustrations covering every aspect of Japanese armour, Samurai Armour provides a compact, accessible guide to this complex, highly decorative protective clothing that still fascinates modern readers.

INTRODUCTION The Samurai

MOST PEOPLE have a general impression of the samurai as heroic warriors, governed by a stern code of conduct and self-discipline, who embodied both fighting power and social virtue. This is a reasonable generalization, but like all social groups the samurai evolved over time. They were shaped by the same forces that created other societies worldwide – conflict, economics and a need to govern.

A depiction of the samurai warriors Ichijō Jirō Tadanori and Notonokami Noritsune locked in battle, showing the distinctive costume and weaponry associated with the samurai class.

The word ‘samurai’ can be translated as ‘those who serve’, which is not exactly the same thing as bushi, or warrior. The samurai class were a social group who served in a military capacity and were therefore definitely warriors, but for much of Japan’s history there were a great many warriors who were not samurai. To a large extent it was service, and therefore being a part of the stable social order, that defined the samurai as more than wielders of weapons.

Disgraced samurai, such as those who had failed to protect their master or who had actively betrayed him, were expected to commit suicide in a particularly unpleasant manner. Ritual self-disembowelment, known as seppuku, was the honourable alternative to defeat and the punishment for failure. It may seem incredible that anyone would actually do this, but the ideal pervaded society to the degree that a samurai who did not do the honourable thing would find his life was not worth living. Seppuku absolved the samurai of blame and ensured he would not bring disgrace upon his family. With such a harsh self-punishment hanging over them, the loyalty of samurai warriors was greatly enhanced.

BUSHIDŌ–CODE OF THE SAMURAI

The code of conduct followed by the samurai, which became known as bushidō, made them reliable servants and loyal warriors. It was not referred to in this manner until the 16th century and the details varied over time, but what did not change was that a warrior had to be loyal and honourable. Treachery and stealthy murder were as much a part of ancient Japanese politics as anywhere else, making reliable guards and vassals essential.

Royal envoys deliver instructions to Ako daimyo Asano Naganori that he is to commit seppuku as punishment for assaulting a fellow court official named Kira Yoshhinaka.

The class system in Japan

The rise of the samurai class to the top of Japanese society was natural. It is common in most cultures for a ruling elite to emerge and for this group to have both military duties and martial prerogatives. It is not unusual that those who risk their lives and engage in hard training to protect a society will want a hand in governing it, and of course those who can fight can take control if they want to. Once in control, limiting the ability of the lower echelons of society to mount a significant challenge greatly assists in maintaining the status quo.

Access to military training is one tool in preserving the social order. A nervous rabble, no matter how well equipped, is unlikely to be able to stand against a seasoned military force. If the rabble also have inferior weaponry and protection, then their fate is sealed. Thus the military elite have tended to rise to the highest social ranks throughout history. There have always been exceptions, but Japanese society was not one of them.

Social stratification had existed for centuries by the beginning of the Edo period (1603–1868) but it was at this time that the rigid class system was implemented in an attempt to stabilize society after decades of civil war. The status of the samurai was confirmed as a governing and military class. The greatest of them, the daimyo, were feudal warlords who maintained a body of samurai warriors to enforce their rule.

The Heiji Rebellion of 1160 was caused by rivalries among powerful samurai clans. It resulted in the destruction of the Sanjo Palace and the imprisonment of the Emperor.

Konishi Yukinaga (1555–1600) is notable for having refused to commit seppuku after defeat. This was due to his religious beliefs as a convert to Christianity.

The economy of Japan was based on rice farming, making farmers the main generators of wealth and naturally the highest of the non-noble classes. Unlike most European societies, farmers ranked above craftsmen, and below craftsmen were the merchants. This concept was based on what each social group produced. Farmers produced rice and were taxed by the samurai class, while craftsmen undertook essential work and made beautiful items that the upper echelons of society desired or even considered necessary to their standard of living. Merchants, who produced nothing, ranked lowest of those within the social order. Some people, such as beggars and religious figures, lay outside the formal hierarchy.

This system was formalized and enforced during the Edo period, but it was based on what had gone before. The earliest samurai were warriors who served feudal lords and were supported by those further down the social order. They became part of the noble or ruling class over time, and their arms and equipment evolved as the nature of warfare and society changed.

Japanese blade weapons of the 14th century: katana, wakizashi and tanto.

Warriors under the command of Kusunoki Masashige defend the castle at Akasaka during the Genko War of 1331 to 1333.

Samurai weapons and their symbolism

Popular culture tends to associate the samurai with their swords, notably the long katana and shorter wakizashi. Worn together, this pair of weapons was known as daishō, and the samurai were the only social class permitted to possess them. The katana became the symbol of the samurai warrior to the point where it was said his soul rested within it. However, swords are weapons for personal combat rather than the battlefield.

While the daishō was a symbol of authority and also a means of enforcing it, it might well be thought of as belonging to the role of the samurai class as governors – a social tool as much as a weapon. Swords were used on the battlefield of course, but most warriors went into action armed with the bow or the spear – weapons much better suited to large-scale combat.

THE BOW (YUMI)

The bow of the samurai was known as the yumi and was of asymmetric construction to enable it to be used on horseback. Making such a weapon required a high standard of craftsmanship, and one could only be used effectively after extensive practice. Only a professional military class could afford the time to become proficient and physically capable of wielding such a weapon, to the point that the lifestyle of the samurai warrior became known as ‘the way of the bow and the horse’.

The quintessential Japanese spear, or naginata, differed from the typical European equivalent in that it had what amounts to a sword blade at its tip. Capable of making slashing attacks as well as thrusting, the naginata was a versatile weapon akin to many European pole weapons. Like other characteristically Japanese weapons the naginata relied on a slashing cut rather than the powerful impact of a heavy blade. A straight-bladed spear known as a yari was also widely used.

Few swords, or weapons with sword-like blades, are heavy enough to chop in the manner of an axe. Instead, they rely on a slicing action. So long as a sharp edge meets the target firmly enough to bite, and remains in contact, the act of drawing the blade through the wound enlarges the hole. In this manner even a relatively light blade can inflict horrific wounds.

The curve on a blade assists the slashing action, but correct edge alignment is essential, as are the body mechanics of the wielder. A tired or poorly trained warrior – or one who has just slightly misjudged the blow – can make what looks like an effective stroke only to find it has failed to put the opponent out of action. Against an unarmoured opponent, almost any contact with the edge of a katana or naginata is likely to be serious, whereas striking that effective blow against an opponent who is moving and is protected by some form of armour is much more difficult.

Satsuma no Kami Tadanori was a key figure in the struggles between the Minamoto and Taira clans known as the Genpei War (1180–85).

Samurai armour and its symbolism

The armour of a samurai warrior was a powerful social symbol as well as a means of personal protection. Its design was intended to intimidate enemies and to remind those of lower rank that they were in the presence of someone important. Practically, it was a force-multiplier and a means of protecting the investment of time and training required to produce an effective warrior.

It takes years to develop the skills required to fight effectively, and to gain the experience necessary for good governance as well as warfare. A young samurai lost in his first battle was a waste of potential, and a seasoned warrior killed by a stray arrow meant that his accumulated wisdom could not be passed on to the next generation. Keeping samurai alive represented more than just self-interest: it was critical to the long-term success of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.12.2025 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Mittelalter |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter | |

| Schlagworte | Ashigaru • Haramaki • Katana • Nagashino • ODA • Tokugawa • Yari |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83886-711-2 / 1838867112 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83886-711-9 / 9781838867119 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich